Jessie Gellatly

Jessie Handyside Gellatly (7 December 1882 – 30 June 1935) was one of the UK's first university-qualified female doctors. She was one of 16 female doctors who served with the Royal Army Medical Corps in the First World War, and served as the medical officer of health (MOH) for Cambridgeshire for most of her life.

Jessie Gellatly | |

|---|---|

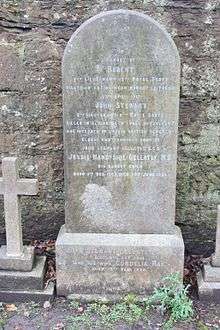

The grave of Jessie Gellatly, Grange Cemetery, Edinburgh | |

| Born | 7 December 1882 |

| Died | 30 June 1935 (aged 52) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Education | University of Edinburgh (1906) |

| Occupation | Physician Medical Officer for Health for Cambridgeshire |

Early life and education

Jessie Handyside Gellatly was born on 7 December 1882. Her parents were Mary Anne Cordelia Rae (1853–1936) and John Stewart Gellatly (1846–1914) of 8 Mary's Place, Stockbridge, Edinburgh. She had several siblings, including her eldest brother, John, who died at Ypres serving in the Royal Scots in the First World War.

In 1901, she entered University of Edinburgh[1] graduating with and MB ChB in 1906. She initially worked at Leith Hospital and then worked for three years as a medical officer for Cadbury in Bourneville. In 1909, she became the medical officer to Walthamstow Sanatorium, and was elected a member of the British Medical Association.[2] She received her doctorate (MD) in 1910[3] and a Diploma in Public Health (DPH) the same year.

Career

Her Edinburgh address was 36 St Albans Road in the Grange. In Edinburgh, she worked with the tuberculosis pioneer Professor Robert William Philip.

In 1914, she moved to Cambridge to take up the position of medical officer of health for Cambridgeshire.

In the First World War, Gellatly was one of the few women co-opted into joining the Women's Medical Unit of the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1916. She embarked in September 1916 and served at the No.65 Hospital in Malta, working there until July 1917, treating the wounded soldiers from Gallipoli. Following attacks on hospital ships in Malta, she was relocated to Thessaloniki. Together with other medical staff and patients, she embarked on HMT Abbassieh on 4 July 1917. It was escorted by HMS Aster and HMS Azalea. HMS Aster hit a mine 1111 mi (18 km) miles off the coast of Malta with the loss of 10 lives. Azalea hit a mine going to her rescue, but with no loss of life. The convoy was forced to return to port to repair at Marsaxlokk harbour. HMT Abbassieh left a second time on 6 July, this time successfully reaching Salonika. A new 65 General Hospital was created there, becoming operational on 30 July. There were eight female doctors in total: Mary Alice Blair (in overall charge), Elizabeth Herdman Lepper, Ida Emilie Fox, Ethne Haigh, Effie Craig, Elizabeth Hurdon, Margaret McEnery, and Jessie Gellatly. They were classed as civilian surgeons and received the same pay (24 shillings plus a final gratuity of £60) and conditions as their male counterparts (a rarity in those days) but had no uniform until April 1918. On 18 September Gellatly transferred from the RAMC to the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps.[4] After the Armistice she worked for the Serbian Relief Fund. In February 1919, she relinquished her commission and returned to civilian life.[5]

Gellatly returned to work as medical officer of health in Cambridgeshire in the summer of 1919. In this capacity, she visited 130 schools twice per year. She lived at 17 Warkworth Street in Cambridge, a mid-terraced townhouse (still standing).

Personal life

She died aged 52 in a nursing home in Cambridge on 30 June 1935 after a short illness. She buried in Grange Cemetery in Edinburgh with her parents. The grave lies to the west side of the central catacombs.

As an unmarried and wealthy woman, Gellatly left most of her monies to the church.[6]

Selected works

- The Glass Cubicle Method of Isolation (1910)

References

- British Medical Journal 13 April 1901

- L/RAMC, Col W Bonnici. "Gellatly Jessie Handyside". maltaramc.com. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- Handyside, Gellatly, Jessie (1910). "Glass cubicle system of isolation, more especially in its application to the smaller isolation hospitals". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - L/RAMC, Col W Bonnici. "Gellatly Jessie Handyside". maltaramc.com. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- The London Gazette 22 February 1919

- Sunday Post (newspaper) 20 October 1935