Jereboam O. Beauchamp

Jereboam Orville Beauchamp (/dʒɛrəˈboʊ.əm ˈɔːrvɪl ˈbiːtʃəm/; September 6, 1802 – July 7, 1826) was an American lawyer who murdered the Kentucky legislator Solomon P. Sharp; the crime is known as the Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy. In 1821, Sharp had been accused in Bowling Green, Kentucky by Anna Cooke of fathering her illegitimate child; it was stillborn.[a] Sharp denied paternity, and public opinion favored him. In 1824, Beauchamp married Cooke, who was seventeen years older than he. She asked him to kill Sharp to defend her honor.

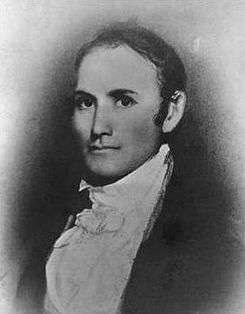

Jereboam O. Beauchamp | |

|---|---|

Etching of Jereboam O. Beauchamp | |

| Born | Jereboam Orville Beauchamp September 6, 1802 |

| Died | July 7, 1826 (aged 23) |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Cooke |

| Parent(s) | Thomas and Sally Beauchamp |

| Motive | Honor killing |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death by hanging |

When Sharp campaigned in 1825 for a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives, opponents revived the story of his alleged illegitimate child by Cooke. They distributed campaign literature claiming the child was mulatto. Enraged, Beauchamp renewed his intention to avenge his wife's honor. In the early morning of November 7, 1825, he tricked Sharp to open the door at his home in Frankfort, and fatally stabbed him.

Beauchamp was convicted of the murder and sentenced to hang. The morning of the execution, he and his wife attempted a double suicide by stabbing themselves with a knife she had smuggled into prison. She died from the attempt; he did not. Beauchamp was rushed to the gallows before he could bleed to death, and was hanged on July 7, 1826. The bodies of Jereboam and Anna Beauchamp were arranged in an embrace and buried in a single coffin, as they had requested. The Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy inspired fictional works such as Edgar Allan Poe's unfinished play, Politian, and Robert Penn Warren's World Enough and Time (1950).

Early life

Jereboam Beauchamp was born September 6, 1802, in the area that is now Simpson County, Kentucky.[1][2] He was the second son of Thomas and Sally (Smithers) Beauchamp.[1] Both parents were devout Christians.[2] He was named after a paternal uncle, Jereboam O. Beauchamp, a state senator from Washington County.[1][2]

Beauchamp was educated at Dr. Benjamin Thurston's academy in Barren County, Kentucky until the age of sixteen.[1] Recognizing that his father could not sufficiently provide for the family, Beauchamp found work as a shopkeeper to earn money for his education. While he saved money, he did not have enough time to pursue his studies. Recommended by Thurston, Beauchamp became preceptor of a school. After saving more money, he returned to Thurston's school as a student. He later worked for the school as an usher.[3]

By age eighteen, Beauchamp had finished his preparatory studies.[3] After observing the lawyers practicing in Glasgow and Bowling Green, he decided to pursue a career in the legal profession.[1]

He particularly admired Solomon Sharp, a young lawyer in his thirties in Bowling Green, with whom Beauchamp hoped to study.[4] In 1820, Beauchamp became disenchanted with Sharp when rumors surfaced that he had fathered an illegitimate child with Anna Cooke, a planter's daughter who lived in Bowling Green.[5] Sharp denied paternity of the child, which was stillborn.[5]

Courtship of Anna Cooke

Beauchamp left Bowling Green to live at his father's plantation in Simpson County, Kentucky, where he convalesced from an illness.[4] He learned that Cooke had become a recluse nearby at her mother's plantation after her public disgrace.[5] Having heard from a mutual friend about her beauty and accomplishments, he decided to meet Cooke.[4] At first, she rejected all attention, but gradually received Beauchamp under his guise of borrowing books from her library. The two eventually became friends, and, in 1821, began courting. Beauchamp was eighteen years old; Cooke was at least thirty-five.[5]

When he proposed marriage that year, Cooke told Beauchamp she would marry him on the condition that he kill Sharp.[6] Beauchamp consented. Against Cooke's advice, Beauchamp traveled immediately to the capital of Frankfort, where Sharp had recently been appointed attorney general by the governor.[7]

Challenges

According to Beauchamp's account, he found Sharp and challenged him to a duel, but Sharp refused because he was not armed. Wielding a knife, Beauchamp took out a second knife and offered it to Sharp, who again declined the challenge. When Beauchamp challenged him a third time, Sharp tried to flee, but Beauchamp caught him by the collar. Sharp fell to his knees and begged Beauchamp to spare his life. Beauchamp kicked him, cursed him for a coward, and threatened to horsewhip him until he agreed to a duel. The next day, Beauchamp looked for Sharp in the streets of Frankfort, but was told he had left for Bowling Green. He went to Bowling Green, only to learn that Sharp was not there. Finally he returned to the home of Anna Cooke.[8]

Following Beauchamp's failed attempt, Cooke decided to lure Sharp to her house and kill him herself. Beauchamp wanted to take action to defend her honor, but she was determined to act for herself. He began teaching her to shoot a gun. Learning that Sharp was in Bowling Green, Cooke sent him a letter condemning Beauchamp's attempt on his life and asking to see him again. Sharp suspected a trap, but replied that he would meet her at the planned time. Hoping to kill Sharp before the meeting, Beauchamp traveled to Bowling Green, but found his target had already left for Frankfort. He had eluded the trap. Beauchamp decided to finish his legal studies in Bowling Green and wait for Sharp to return there.[9]

Beauchamp was admitted to the bar in April 1823. He and Anna Cooke married in June 1824.[2] Still determined to defend the honor of his wife, Beauchamp devised a ruse to lure Sharp to Bowling Green. He wrote letters to Sharp under various pseudonyms, each asking for his help in some sort of legal matter, and each sent from a different post office. When Sharp failed to respond, Beauchamp decided to go to Frankfort again and confront him.[10]

Murder of Solomon Sharp

In Frankfort in 1825, Sharp was in the middle of a bitter political battle known as the Old Court-New Court controversy.[11] He identified with the New Court, or Relief party, which promoted a legislative agenda favorable to debtors.[11] In opposition was the Old Court, or Anti-Relief party, which worked to secure the rights of creditors to collect debts. Sharp had served as the state's attorney general under New Court governors John Adair, whose term lasted until August 1824, and Joseph Desha, who succeeded him in office.[11] The New Court party's power was beginning to wane.

In 1825, Sharp resigned to run for a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives.[12] During the heated campaign, opponents raised the issue of his alleged seduction of Anna Cooke.[13] Old Court partisan John U. Waring had handbills distributed that alleged that Sharp had denied paternity of Cooke's illegitimate child because it was a mulatto and likely fathered by a Cooke family slave.[2] Sharp won the election, defeating John J. Crittenden.[13]

Whether Sharp had made the claim is uncertain, but Beauchamp believed he had.[13] He planned to murder him and flee with Anna to Missouri.[14] He would murder Sharp in the early morning of November 7, 1825, when the new legislature convened its session, as he hoped that suspicion would fall on Sharp's political enemies.[14] Three weeks prior to that date, Beauchamp sold his property, telling his friends that he was planning to move to Missouri.[14] He hired laborers to help load his wagons two days before the planned murder.[14]

Beauchamp's plan was complicated by a warrant sworn out against him by Ruth Reed. She sued him for support of her illegitimate son, born on June 10, 1824, claiming he was the father. Beauchamp later said he had ignored the warrant, dated October 25, 1825, on the advice of a friend who termed it harassment. He also said he had arranged for the warrant, as an excuse to be in Frankfort to kill Sharp. The historian Fred Johnson says that Beauchamp likely added the warrant into his story after the fact, as a means of damage control. It hardly looked good for him to have committed the act for which he ostensibly killed Sharp.[15]

In preparation, Beauchamp packed a change of clothes, a black mask, and a knife with poison on the tip, to be used as the murder weapon.[16] Finding all the inns filled when he arrived at Frankfort, he took lodging at the residence of Joel Scott, warden of the state penitentiary.[17] Between nine and ten o'clock that evening, Beauchamp went to Sharp's home.[18] Dressed in disguise, he carried his usual clothes and buried them along the bank of the Kentucky River for retrieval following the murder.[17] Discovering that Sharp was not home, Beauchamp looked for him in the city, finding him at a local tavern.[18] He returned to Sharp's house to wait for him, and saw him return at midnight.

At two o'clock in the morning, Beauchamp thought the household was quiet. In his Confession, he described the murder of Sharp:

I put on my mask, drew my dagger and proceeded to the door; I knocked three times loud and quick, Colonel Sharp said; "Who's there" - "Covington," I replied. Quickly Sharp's foot was heard upon the floor. I saw under the door as he approached without a light. I drew my mask over my face and immediately Colonel Sharp opened the door. I advanced into the room and with my left hand I grasped his right wrist. The violence of the grasp made him spring back and trying to disengage his wrist. He said, "What Covington is this". I replied John A. Covington. "I don't know you," said Colonel Sharp, I know John W. Covington". Mrs. Sharp appeared at the partition door and then disappeared, seeing her disappear I said in a persuasive tone of voice, "Come to the light Colonel and you will know me," and pulling him by the arm he came readily to the door and still holding his wrist with my left hand I stripped my hat and handkerchief from over my forehead and looked into Sharp's face. He knew me the more readily I imagine, by my long, bush, curly suit of hair. He sprang back and exclaimed in a tone of horror and despair, "Great God it is him," and as he said that he fell on his knees. I let go of his wrist and grasped him by the throat dashing him against the facing of the door and muttered in his face, "die you villain". As I said that I plunged the dagger to his heart.

— Jereboam Beauchamp, Confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp, pp. 39–41

Sharp died within moments. Fleeing the scene, Beauchamp went to the river to retrieve his clothes, where he changed and sank his disguise in the river with a stone. He returned to his room at the house of Joel Scott.[18]

When the Scott family awoke the next morning, Beauchamp emerged from his quarters. He feigned surprise when told of the murder and was apparently believed at the time. After being told there were no suspects yet, he called for his horse and began his return trip of four days to Bowling Green. Arriving, he told his wife Anna that Sharp was dead. The next morning, a posse from Frankfort arrived and told Beauchamp that he was under suspicion for the murder. He agreed to return with the men to Frankfort and face the charge.[19]

Trial for murder

Beauchamp arrived in Frankfort on November 15, 1825.[20] New Court partisans talked of Sharp's murder as the work of the Old Court party, just as Beauchamp had hoped.[21] One suspect was Waring, who had printed the handbills critical of Sharp.[20] Known as a violent man, he had both political and personal motivation for the crime.[20] He was cleared of suspicion when investigators learned that, at the time of the murder, Waring was in Fayette County recovering from unrelated injuries.[20]

Suspicion moved to Beauchamp, as he was loyal to the Old Court Party, and was known to hate Sharp for his political principles.[22] People knew of Sharp's earlier alleged involvement with Anna Cooke before her marriage to Beauchamp. Witnesses placed Beauchamp in Frankfort the night of the killing, and his host, Joel Scott, said that he had heard Beauchamp leave the house during the night.[20] After presenting preliminary testimony, Commonwealth's Attorney Charles Bibb asked for additional time to assemble more witnesses.[20] Beauchamp assented to the request.[20] A second delay pushed the hearings back to mid-December.[20]

The dagger taken from Beauchamp at his arrest did not match the wound on Sharp's body.[20] (In his Confession, Beauchamp claimed to have buried the murder weapon by the bank of the river near where the murder took place. That knife was never found).[23] Beauchamp's shoe did not match a track found outside Sharp's house the morning of the murder.[20] The posse lost a handkerchief found at the scene of the crime and believed to belong to the murderer.[24] (Beauchamp later claimed to have stolen and burned it after the posse had gone to sleep one night).[25]

Several witnesses testified against him. The widow Eliza Sharp testified that the voice of the killer was distinct. A test was devised allowing Mrs. Sharp to hear Beauchamp's voice; she immediately identified it as that of the killer. (Beauchamp claimed he had disguised his voice on the night of the murder and thought Mrs. Sharp would not recognize it). Patrick Henry Darby, an Old Court partisan, claimed that in 1824, he had a chance encounter with the man he now knew as Beauchamp. Darby said the man – a stranger to him at the time – had asked for Darby's help in prosecuting an unspecified claim against Sharp. The man then identified himself as the husband of Anna Cooke and said he intended to kill Sharp. Based on the circumstantial evidence, Beauchamp was held for trial at the next term of the circuit court in March 1826.[26]

Beauchamp's uncle Jereboam assembled a legal team for his nephew that included former U.S. Senator John Pope.[27] The grand jury convened in March and returned an indictment against Beauchamp for Sharp's murder.[27] Giving Beauchamp the time he requested to gather witnesses, the court scheduled a special session in May specifically for his trial.[27]

Beauchamp's trial began May 8, 1826.[27] After a change of venue was denied, Beauchamp pleaded innocent to the charge against him.[28] A jury was empaneled, and testimony began May 10.[28] Eliza Sharp recounted the events of the night of the murder and reiterated that Beauchamp's voice was that of the murderer.[28] John Lowe, a magistrate of Simpson County, testified that he had heard Beauchamp threaten to kill Sharp, and said that on Beauchamp's return from Frankfort, he saw him waving a red flag and heard him tell his wife that he had "gained the victory".[28] Patrick Darby repeated his testimony of the 1824 meeting between him and Beauchamp.[29] Darby said that Beauchamp had told him that Sharp offered him one thousand dollars, a slave girl, and 200 acres (0.81 km2) of land if he and his wife Anna would leave him (Sharp) alone.[29] As Sharp had apparently reneged on the promise, Beauchamp told Darby he was going to kill the man.[29] Other witnesses testified that Beauchamp habitually referred to Sharp's friend, John W. Covington, as "John A. Covington", the name used by the murderer to gain entry to Sharp's house.[30]

Testimony in the trial concluded on May 15, 1826; summations concluded four days later.[31] Despite the lack of physical evidence, the jury deliberated only an hour before convicting Beauchamp of Sharp's murder.[31] He was sentenced to death by hanging on June 26 of that year.[32] Beauchamp requested a stay of execution to write a justification for his actions.[32] The stay was granted, and the execution was rescheduled for July 7, 1826.[32] Though Anna Beauchamp was questioned, a charge against her for being an accessory to the crime was dismissed.[33]

Execution by hanging

While imprisoned and awaiting execution, Beauchamp wrote a confession. He accused Patrick Darby of perjury with regard to the alleged 1824 meeting between them.[15] Many believed Beauchamp's accusation was meant to curry favor with New Court governor Joseph Desha – who considered Darby a political enemy – and to secure a pardon from him.[34] When Beauchamp finished the confession in mid-June 1826, his uncle, Senator Beauchamp, took it to the state printer for immediate publication.[15] An Old Court supporter, the printer refused to publish it.[34]

Anna Beauchamp joined her husband in his cell in the dungeon; the only entry was through a trap door at the top of the room. During their incarceration, they tried to bribe a guard into allowing them to escape.[35] When that failed, they tried to pass a letter to Senator Beauchamp asking for help to escape, an attempt which likewise failed.[35] Both the senator and the younger Beauchamp asked for a pardon from Governor Desha, but to no avail.[34] Beauchamp's final request to Desha for a stay of execution was rejected July 5, 1826.[35] With the last hope exhausted, the couple attempted a double suicide by drinking a vial of laudanum which Anna had smuggled into the cell.[36] Both survived. The following morning, Jereboam and Anna were put on suicide watch and threatened with separation.[37]

The night before the execution, Anna took a second dose of laudanum but was unable to keep it down.[37] On July 7, 1826, the morning of the scheduled execution, Anna asked the guard to give her privacy to dress. Once the guard left, Anna revealed to Beauchamp that she had smuggled in a knife, and she and her husband stabbed themselves.[38] Anna was taken to a nearby house to be treated by doctors.[39]

Too weak to stand or walk, Beauchamp was loaded onto a cart to be conveyed to the gallows. He begged to see Anna, but the guards told him she was not seriously injured. The guards finally allowed him to see Anna, and Beauchamp was angered that they had underplayed her critical condition. He stayed with her until he could no longer feel her pulse; then the guards took him to the gallows to be hanged before he died of his stab wounds.[40]

Beauchamp asked to see Patrick Darby, who was among the assembled 5,000 spectators. Beauchamp smiled and offered his hand, but Darby declined the gesture. Beauchamp publicly denied that Darby had any involvement with Sharp's murder, but accused him of having lied about their 1824 meeting. Darby denied the death march accusation and tried to get Beauchamp to retract it, but the prisoner was moved on to the gallows.[41]

Two men supported Beauchamp as the noose was put around his neck. He asked for a drink of water, and the band to play "Bonaparte's Retreat from Moscow".[37] At his signal, the cart moved out from under him, and he died after a brief struggle.[37] His father requested his body. Following Beauchamp's earlier instructions, he had the bodies of Jereboam and Anna arranged in an embrace and buried them in the same coffin. A poem written by Anna was etched on their double tombstone.[42]

Senator Beauchamp eventually found a publisher for his nephew's Confession. The first printing ran on August 11, 1826. Sharp's brother, Dr. Leander Sharp, attempted to counter Beauchamp's Confession with Vindication of the Character of the late Col. Solomon P. Sharp, which he wrote in 1827. In this book, Dr. Sharp claimed to have seen a "first version" of the confession in which Beauchamp implicated Darby. Darby threatened to sue Dr. Sharp if he published Vindication, and John Waring threatened to kill him if he did so. Sharp did not release the manuscript and hid it in his house. The completed printed version was found in 1877 during a remodel of Sharp's house.[15]

In popular culture

- Edgar Allan Poe's play, Politian, was based on the events above.[43]

- Robert Penn Warren's World Enough and Time was also inspired by them.[43]

Notes

^[a] Sources variously spell the name as Anna Cooke, Anna Cook, Ann Cooke, and Ann Cook.

References

- Cooke, p. 126

- Bruce, p. 11

- St. Clair, p. 285

- St. Clair, p. 286

- Cooke, p. 127

- Cooke, p. 128

- St. Clair, p. 289

- St. Clair, pp. 290-292

- St. Clair, pp. 293–294

- St. Clair, p. 294

- Cooke, p. 130

- Cooke, p. 134

- Cooke, p. 135

- St. Clair, p. 295

- F. Johnson, New Light on Beauchamp's Confession?

- St. Clair, p. 296

- Cooke, p. 136

- St. Clair, p. 297

- St. Clair, pp. 299–301

- Bruce, p. 15

- St. Clair, p. 302

- Kimball, p. 25

- Beauchamp, p. 42

- Bruce, pp. 15–16

- Beauchamp, pp. 60, 64–65

- Bruce, pp. 16, 33

- Bruce, p. 20

- Bruce, p. 21

- Bruce, p. 22

- Bruce, pp. 23–24

- Bruce, p. 26

- Kimball, p. 18

- Bruce, p. 27

- Bruce, p. 29

- Cooke, p. 145

- Cooke, pp. 145–146

- Bruce, p. 8

- Cooke, p. 146

- St. Clair, pp. 305–307

- St. Clair, p. 307

- L. Johnson, p. 54

- St. Clair, p. 308

- Whited, p. 404–405

Bibliography

- Beauchamp, Jereboam O. (1826). The confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp : who was hanged at Frankfort, Ky., on the 7th day of July, 1826, for the murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Bruce, Dickson D. (2006). The Kentucky Tragedy: A Story of Conflict and Change in Antebellum America. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-3173-3.

- Cooke, J.W. (April 1998). "The Life and Death of Colonel Solomon P. Sharp Part 2: A Time to Weep and A Time to Mourn" (PDF). The Filson Club Quarterly. 72 (2).

- Johnson, Lewis Franklin (1922). Famous Kentucky tragedies and trials; a collection of important and interesting tragedies and criminal trials which have taken place in Kentucky. The Baldwin Law Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 2005-03-08. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- Johnson, Fred M. (1993). "New Light on Beauchamp's Confession?". Border States Online. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- Kimball, William J. (January 1974). "The "Kentucky Tragedy": Romance or Politics". Filson Club History Quarterly. 48.

- St. Clair, Henry (1835). The United States Criminal Calendar. Charles Gaylord. ISBN 1-240-06957-X. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- Whited, Stephen R. (2002). "Kentucky Tragedy". In Joseph M. Flora and Lucinda Hardwick MacKethan (ed.). The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People. Associate Editor: Todd W. Taylor. LSU Press. ISBN 0-8071-2692-6. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

Further reading

- Bruce, Dickson D. (2003). "The Kentucky Tragedy and the Transformation of Politics in the Early American Republic". The American Transcendental Quarterly. 17.

- Coleman, John Winston (1950). The Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy; An Episode of Kentucky History during the Middle 1820s. Frankfort, Kentucky: Roberts Print. Co.

- The Life of Jeroboam O. Beauchamp : Who Was Hanged at Frankfort, Kentucky, for the Murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Frankfort, Kentucky: O'Neill & D'Unger. 1850.

- Sharp, L.L. (1827). Vindication of the Character of the late Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Frankfort, Kentucky: Amos Kendall and Co. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2013-04-02., scanned version online, University of Kentucky

- Thies, Clifford F. (2007-02-07). "Murder and Inflation: the Kentucky Tragedy". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved 2008-01-24.