Jean Dollfus

Jean Dollfus (September 25 1800 – 21 May 1887) was a French industrialist who grew a textile company, Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie (D.M.C.), in Mulhouse. Dollfus was a leading figure in a philanthropic society which constructed a company town that sold houses at cost to the town's workers. Dollfus also helped publish an encyclopedia of needlework.

Jean Dollfus | |

|---|---|

| Born | Jean Dollfus-Mieg September 25, 1800 Mulhouse, France |

| Died | May 21, 1887 (aged 86) Mulhouse, France |

| Occupation | industrialist |

Life

Jean Dollfus was born in Mulhouse, France, in 1800, the son of Daniel Dollfus and Anne Marie Mieg.[1] He was born into a family that owned a textile business established in the 18th century. His parents wrote their surname as Dollfus-Mieg, and Daniel used this name to re-brand his uncle's textile company as Dollfus-Mieg & Compagnie, or D.M.C., in 1800.[1] Whilst studying in Leeds, Jean Dollfus found out about Mercerised cotton. This was a new technique of chemically treating cotton to increase not only its strength but also its appearance,[1] a discovery that he would apply to the textile business.

Dollfus was a leading member of the Societe Industrielle de Mulhouse. In 1851 he published a letter to them where he advocated free trade. Dollfus noted that the French cotton trade was stagnant whilst between 1830 and 1850 the British had doubled their consumption of raw cotton. Dollfus believed that taxes levied by the French in order to protect French workers were in fact preventing industrial expansion.[2]

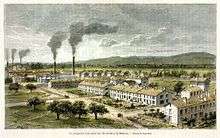

In 1852 the Societe Industrielle de Mulhouse began construction on cités ouvrières, or worker's towns. This philanthropic endeavor was not led by a single company but involved numerous leading citizens, although Dollfus was credited with leading the work. Henry Roberts is credited with the inspiration and Emile Muller drew up the designs. Construction continued for the next 45 years.[3] The development was so novel and admirable that Napoleon III made 30,000 francs available to assist the project[4] and Dollfus became the Mayor of Mulhouse from 1863 to 1869. By 1885 the society had constructed 1,060 workers' houses in Mulhouse and had sold 775 of them at cost to their occupants. Each of these occupants, after about 15 years, owned a small house with a small garden.[4]

Dollfus commissioned Pierre-Auguste Renoir to paint a copy of a painting by Delacroix. The painting was completed by 1876 and was not a true copy, as Renoir had adapted the colours and brush work to an impressionist style. This painting remained in the Dollfus family until 1911 and it is now housed in the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts.[5]

In 1884 Dollfus signed an agreement with Thérèse de Dillmont, a textile teacher and writer. She came from Vienna to work with him.[1] She wrote an Encyclopedia of Needlework that was translated into 17 languages. This book had product placement as it recommended products from Dollfus' company,[6] and established Dollfus' company as a publisher of textile patterns. After Dillmont died, the brand was continued and in 2004 a Russian translation of Dillmont's book was published.[7]

Dollfus died in 1887 and his business continued under the leadership of his grandchildren.[4]

References

- DMC History Archived 2016-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, DMCCreative, retrieved 27 October 2014

- Hunt, Freeman; et al. (1851). Merchants' Magazine and Commercial Review, Volume 25. p. 213.

- Curl, James Stevens (2006). A dictionary of architecture and landscape architecture (2 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 190. ISBN 0198606788.

- Taken from the DMC Historical French Chronicles, DMC Threads, retrieved 29 October 2014

- European paintings in the collection of the Worcester Art Museum. Worcester, Mass.: The Museum. 1974. p. 276. ISBN 0870231693.

- Ledbetter, Kathryn (2012). Victorian Needlework. Crafts & Hobbies. p. 73. ISBN 0313386609.

- Rachel P. Maines (19 June 2009). Hedonizing Technologies: Paths to Pleasure in Hobbies and Leisure. JHU Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8018-9794-8.