Japanese fashion as social resistance

Following the old Japanese adage of “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down” (出る釘は打たれる deru kugi wa utareru), the Lolita (ロリータ roriita) and Ganguro (ガングロ) fashions have been met with much disdain as marginal subgroups of Japanese culture.[1] Clothing is one of the easiest ways to differentiate oneself in Japanese society, and even though Ganguro is much more overt and shocking in this expression and Lolita has somewhat more subtle methods, both harken to Western ideals of attractiveness, with Ganguro girls evoking the California girl or the black hip-hop aesthetic and Lolita calling upon Rococo, the Victorian era, and Edwardian era in Western Europe.[2] This is directly in conflict with nationalism and the homogenous image in Japan. Looked at more closely, this sort of dress could bring shame upon the family because there is too much attention being drawn to the child, and can conflict with ideas of conduct, social roles, and rebellion within Japanese filial piety (親孝行 oyakōkō) and Confucianism, both of which are major parts of the structure of Japanese society.

There has been some speculation that these fashions are expressions of psychological discontent, a way of finding groups that are accepting emotional outlets, of receiving attention, as well of expressing resentment in the face of neglect at home from busy working parents or isolation, bullying, and stress at school.[3]

Ganguro

Characteristics

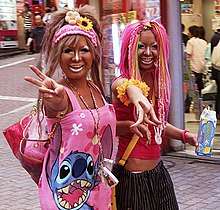

Ganguro style is characterized by dyed hair, tanned skin, and a heavy use of makeup. Far from traditional Asian styles, it emphasizes standards of beauty that seem more reminiscent of California than Japan. Hair colors can range from blond and orange to a bleached white. Although makeup trends have changed throughout the years, most Ganguro styles incorporate a non-conventional use of white concealer with a skin-tan that is achieved through either cosmetic products or extensive tanning. Different sub-groups of Ganguro can often be distinguished by their eye makeup with white makeup appearing above the eyes in Ganguro and below the eyes in a later branch referred to as Yamanba.[4]

Individual fashion focuses on bright colors and an abundance of accessories. Ganguro girls can be seen sporting tie-dye, miniskirts, bulky jewelry, and platform shoes. Yamanba is often associated with Hawaiian prints and facial stickers, although these particular accessories have fallen out of style recently.

Historical Background

Ganguro first developed in the 90's, drawing on both global stimuli and Japanese cultural climate. Although the trend is a fusion of many different factors, R&B artist Namie Amuro and British model Naomi Campbell are seen as its primary influences (Joseph & Holden). Amuro often wore miniskirts and platform boots, which became a staple in Ganguro style. Both of these women helped to popularize dark skin in Japan, which ran contrary to previous cultural ideals. Although these traits are valued within the Ganguro sub-culture, they are often still ridiculed and rejected within mainstream society.

Yamanba, which developed as a branch of Ganguro, incorporated more elements from traditional Japanese culture. Before the name Yamanba became associated with the fashion trend, it referred to a mountain hag who was the namesake of the Yamanba (noh play). The play tells the story of a traveler who encounters this woman and questions whether she is a spiritual being or simply an old woman. Drawings and masks from this play depict Yamanba as a woman with a headpiece or wig of shaggy white hair, much like the bleached and backcombed hair of today's Yamanba girls. As was traditional for characters Noh plays, Yamanba's actor was clothed in a mask and complex costume.[5] Today, participants in Yamanba fashion define themselves by their unusual clothing and a ‘mask’ of over the top makeup.

Cultural Perception

Ganguro girls tend to perceive others from their group positively. They are more comfortable among girls with appearances similar to their own and tend to find them more approachable than outsiders. In this way, Ganguro has served not only as an alternative fashion, but also as a social community or a group of social communities. Many of these groups require members to wear specific items that fit within the style or have specific initiation practices. In extreme cases, groups have been known to inflict harm on others, as in the case of Girl A, or even engage in murder or cannibalism as the popularity of Japanese icons such as has grown.[6] Sasebo slashing Individuals or groups who follow Ganguro style have been able to connect through media, social networking, style magazines like Cawaii!.[1]

Mainstream society and media has historically not been as accepting of Ganguro and Yamanba. Because they reject traditional aesthetic values, they have been rejected as rebellious and troubled. Some go so far as to label them as unclean and unstable.[4] In Ganguro's early days, this treatment left girls feeling rejected and uncomfortable in normal society. Marginalization like this has perhaps strengthened the group identity of Ganguro girls and driven them towards a social sphere based on in-group connections.[1]

Analysis of Ganguro as Resistance

While Ganguro is on one hand just the formation of another social group with different prescriptions of appearance and behavior than the overall society, it can also be seen as an attempt at removal from society. The yamanba is said to be an ugly mountain hag in Japanese mythology from which a subsection of Ganguro adopted the appearance of white-painted noses and under-eyes. In the context of Shinto, mountains are sacred, so it is possible that this portion of the Ganguro girls were purposely evoking the essence of the yamanba in the mountains so as to be inaccessible in an otherworldly, spiritual sense as well as physically through their shocking looks.[7]

Ganguro and its predecessors can be said to be in direct opposition to both traditional conceptions of Japanese school children and Japanese women as meek, obedient, and undistracting, as well as in direct opposition to traditional Japanese ideals of beauty. Ganguro, as the Kogal culture before it, is an expensive fashion and requires much money to create the aesthetic.[2] More complexly, as a characterization of the affluent Californian valley girl, it may be meant to emanate an overall appearance of affluence and wealth. This may be considered as immodesty and selfishness, both of which are frowned upon in Japanese society.

Furthermore, Ganguro girls have a reputation, though perhaps of dubious factualness, of being delinquents in one form or another,[4] unambitious, and poor performers in school, which causes much public as well as familial disdain.[3] Their disruptive appearance and possibly disruptive behavior has been analyzed as a struggle for individual representation and attention within the serious school atmosphere.[3] Again, modification of fashion (shortening of skirts, coloring hair, interesting makeup) is one of the most accessible ways to express individuality in Japan.

Lolita

Lolitas are said to use their sense of fashion to distinguish themselves from mainstream society because clothing seems to be one of the few ways to differentiate a person in Japanese society. This young person that chooses this fashion as a form of rebellion does this because they still wish to belong to a group just not a mainstream group. The Lolitas appear to be rebelling against unladylike fashion and behaviors associated with other fashion styles such as Ganguro mentioned above.[2]

Historical background

In the 1980s it is believed that Lolita fashion began in Harajuku, Tokyo when the Omotesando and Takeshita-dori streets were closed to traffic on Sundays. In this open area youths and street performers gathered and soon started appearing in unconventional outfits which gradually developed into recognisable styles such as lolita, gyaru or kogal, decora and Ganguro.[8] These styles continue on today and have gained popularity all over the world though the reasoning behind choosing to wear these styles is different for every individual.

The Styles

By looking over Lolita fashion you can see that it gets its influences from a variety of eras. The most easily recognizable influence comes from the Victorian era. The lolita take on this era is closer in resemblance to children's clothes from this era than adults’. Skirts worn by lolitas are generally around knee-length rather than full floor-length gowns that you would expect to see from this era.[8] Influences also come from other eras such as the 1950s and the French Rococo style which make up different subsections of lolita fashion. While lolita can have a historical look and feel, it is not from any particular period or region and tends to blend multiple historical looks together. There are 16 and counting different styles of this Lolita fashion. These include aristocrat, casual Lolita, classic Lolita, cosplay Lolita, country Lolita, ero Lolita, gothic Lolita, guro Lolita, hime Lolita, kodona, kuro Lolita, punk Lolita, sailor Lolita, shiro Lolita, sweet Lolita, wa Lolita. through these fashions Lolitas also tend to adopt stricter manners and be slightly more cautious about how they carry themselves. There are many boys who will dress in a Lolita outfit. This has been made popular by the rock musician Mana who owns a Lolita brand named Moi-même-Moitié. This style can sometimes be confused with a sexual fetish. This could be due to the short skirts, they can wear or it can be drawn from its namesake the novel ‘Lolita’ by Vladimir Nabokov. The lolita subculture emphasizes modesty and youthfulness and is not considered overtly sexual by its followers.

Lolita as a rejection to the formal Japanese life

Some Lolitas choose this fashion or lifestyle, as some see it, because they are still expected in some ways to follow the traditional role of a Japanese woman when they would rather live on their own and spend their money on lolita attire. It is true that Japanese women of today have more societal roles than those of their mothers. However they are still expected to enter employment only until marriage and childbirth and while employed they are also still generally placed in lower roles than men in the workplace.[9] One form of Lolita, called goth lolita, appears at first glance to be a huge rejection of societal expectations in favor of a luxurious and responsibility-free life from the traditional Japanese culture and society. Lolita generally emphasises childlike innocence and purity, which tends to be expressed in ‘sweetness’ and optimism while Goth veers more towards morbidity, sexual fetishism and pessimism. Gothic lolita has a fascination with religious imagery and Victorian nostalgia while still keeping to the “sweetness” norms of the overall lolita fashion.[9] Because of the social norms of expected sweetness constructed within the lolita society itself this fashion now serves as an alternative to the local culture rather than an outright rebellion against their families and society. Lolita also continues to exist with little resistance from society because of the Japanese emphasis on downplaying conflict.

Analysis of Lolita as Resistance

Lolita as a fashion follows a more traditional Japanese manner of resistance by being subtle and subversive. Its aesthetics are demure and keep some elements of traditional Japanese beauty while also being clearly unusual and nonconformist by incorporating historical European aesthetics of beauty. In this way, while Lolitas are still very feminine and modest, they found a way to break out of the homogenous manner of appearance and begin toying with new forms of identity and femininity.[9] Some have argued that the fashion fights against traditional expectations of marriage and a woman's role in family life by perpetualizing a childlike innocence (if not in manner, at least in appearance) to avoid the pressure of marriage and adult life in Japan.[2] Many claim that Lolita fashion also fights the patriarchal system in subtle ways. For instance, molestation on crowded Japanese subways is a big problem in Japan,[10] but the Lolita fashion incorporates a childlike or doll-like image as well as many heavy layers, both of which would make this action much more difficult. It is a manner of protecting oneself while not being outspoken, which is a subtle form of resistance.

Lolita is also an expensive fashion, requiring much fabric, many accessories, and specialty items. If one does not make the clothing and accessories themselves (and even if they do), the expense required of maintaining the appearance might be considered greedy, which is highly frowned upon in Japanese society.

Conclusions

As values have changed and continue to change throughout Japan, some large contradictions are appearing in social expectation and place, leaving Japan's younger generation to try to make sense of the conflicting messages of their role compared to their desire to express more independence. Ganguro and Lolita can be said to be expressions of a bigger social issues at large – that of Japan's continual disenfranchisement of youth in the failure to recognize their individuality and power, as well as issues in the family as a result of rapid changes Japan has seen in recent decades.[11] These alternative fashions, whether overt and ‘loud’ in manifestation like Ganguro, or exaggeratedly feminine like Lolita, are less serious than some of the many other social issues that have arisen as a result, while still managing to make statements about personal aesthetics, individual expression, and need for acknowledgment.

See also

- Japanese fashion

- Ganguro

- Kogal

- Lolita fashion

References

- Joseph, Todd; Holden, Miles. "Japan's Mediated 'Global' Identities". Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- Hollimon, Jessie. "Japanese Subculture: Kogals and Lolitas, Rebellion or Fashion". Post Bubble Culture.

- Liu, Xuexin. "The Hip Hop Impact on Japanese Youth Culture". SEC/AAS.

- "Ganguro, Yamanba, and Manba".

- "Masks for Yamanba". Japanese Performing Arts Resource Center.

- Issei Sagawa

- "acred Sites and Pilgrimage in Japan".

- "Lolita Fashion". Archived from the original on 2012-12-24. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- Porzio, Laura. "Lolita style and its embodied practices between resistance and urban fashion" (PDF).

- "On Tokyo's Packed Trains, Molesters Are Brazen". New York Times. December 17, 1995.

- Hashimoto, Akiko; Traphagan, John (December 4, 2008). Imagined Families, Lived Families: Culture and Kinship in Contemporary Japan. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791475782.