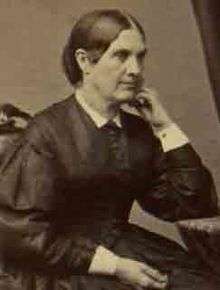

Jane Hunt

Jane Clothier Hunt or Jane Clothier Master (26 June 1812 – 28 November 1889) was an American Quaker who hosted the Seneca Falls meeting of Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Jane Hunt | |

|---|---|

Jane Clothier Hunt | |

| Born | Jane Clothier Master June 26, 1812 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | November 28, 1889 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Organising pre-meeting of Seneca Falls Convention |

| Spouse(s) | Richard Hunt |

Life

Hunt was born in Philadelphia in 1812 to William and Mary Master. She moved to Waterloo in New York in 1845 when she married fellow Quaker Richard Pell Hunt, a prominent local businessman and landowner.[1]

As progressive Quakers, Hunt and her husband were believers in social reform and humanitarian causes. They were both active supporters of abolitionism and the women's rights movement.[1] Hunt's home in Waterloo is thought to have functioned as a station of the Underground Railroad, with a carriage house that was converted to a way station for fugitive slaves.[2]

Women's membership and role was an important topic of discussion in Hunt's Quaker community, and she worked actively to improve women's position in the church.[3] Hunt was one of the members of a local Quaker monthly meeting which proposed removing the official inequality between men's and women's meetings described in the book of discipline; this proposal was adopted at a regional level at the Genesee Yearly Meeting in 1838.[4]

Hunt had four children with her husband (one died at childbirth), and was step-mother to Richard's three children from a previous marriage. Richard Hunt died on November 7, 1856. After his death, Hunt continued to live in the family home.[5]

The Seneca Falls Convention

In 1848, Jane Hunt was part of a group of women who invited the reformer Lucretia Mott to visit New York, with Hunt offering to host the gathering at her home.[5] Mott stayed with her pregnant sister, Martha Wright, who lived in the area.[6] Hunt invited a number of Quaker women including Mary Ann M'Clintock as well as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was not a Quaker. The day at Hunt's home was an important re-meeting between Mott and Stanton, who had met eight years before at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. They had both been invited to the convention but they had to suffer the indignity of sitting separately and not being allowed to speak because they were women.

As a result of the meeting at Hunt's home on July 9, it was agreed to arrange an open meeting at Seneca Falls later in the month. Hunt and the other women present drafted a call for attendees that was published in the Seneca County Courier on July 14.[7]

The assembly that would come to be known as the Seneca Falls Convention is considered to be the first organized meeting about women's rights.[5] Hunt and her husband were both signatories to the Declaration of Sentiments and attended the Convention.

Legacy

Hunt's philanthropy after her husband's death included funding land for a chapel for Saint Paul's Church in Waterloo. The Hunt House is a registered historic site.[8]

References

- Weber, Sandra S. (1985). "The Hunts". Special History Study Women's Rights National Historical Park Seneca Falls, New York. U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2015). The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations. Routledge. p. 280. ISBN 1317454162.

- Lerner, Gerda. "The Meaning of Seneca Falls: 1848-1998" (PDF). Dissent (Fall 1998): 36.

- Densmore, Christopher. "Radical Quaker Women and the Early Women's Rights Movement". Quakers & Slavery. Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Judith Wellman, "Jane Hunt", Historical New York, National Park Service, Retrieved 16 August 2016

- Martha C Wright, nps.gov; retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "Image 1 of National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection copy - The first convention ever called to discuss the civil and political rights of women, Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19, 20, 1848". Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Yocum, Barbara A. "HUNT HOUSE: Women's Rights National Historical Park Seneca Falls and Waterloo, New York" (PDF). National Park Service Historic Architecture Program. Retrieved 6 January 2019.