James Fairman

James Fairman (1826, Glasgow -12 March 1904, Brooklyn, New York) was a Scottish-born American landscape painter, art teacher, art critic and military officer.

Biography

His father, Laurenz Fehrman, was a Swedish military officer who served under King Charles XIV John in the Coalition Wars. When the King changed sides, he fled to Scotland, where he married James' mother, Mary Farquharson Black.[1]

In 1832, after his father's early death, his mother decided to emigrate to the United States. They settled in New York City. In 1842, having shown some aptitude for drawing, he began attending evening classes at the National Academy of Design. Upon the recommendation of the portrait painter, Frederick Styles Agate, he became a full-time student. Following his graduation, he found employment as an apprentice at Harper & Brothers publishing, in Manhattan.

In 1851, he paid a visit to London to see the Great Exhibition. He later described what he saw there as his "revelation". Over the next ten years, he became increasingly involved in the Abolitionist movement and discovered that he had a talent for public speaking; attending a course on the subject taught by Edward Delafield Smith. In 1858, when a dispute arose over removing Bible study from the New York public schools, he opposed the change, ran for a seat on the school board committee, and was elected. An unsuccessful campaign for Congress soon followed.

Civil War service

In 1861, a few months after the Civil War began, he enlisted as a Captain with Company B of the 10th New York Infantry. He was, however, released after four weeks for trying to recruit his own regiment. He then became a recruiter for the 4th Excelsior Regiment, on behalf of Congressman Daniel Sickles. Having little success there, he applied to the 96th New York Volunteer Infantry and was accepted as a Colonel. After only three weeks of training, his unit took part in the Peninsula Campaign. During this time, four complaints were brought against him as the result of disputes with subordinate officers. He was also reprimanded for insulting a superior officer, General William High Keim; calling him a "Pennsylvania Dutchman" who obtained his position through political influence. When similar complaints followed, he was asked to resign and he did, in September 1862.[2]

Later career

He then returned to New York and opened his own studio. He also gave lectures on behalf of the Cooper Union. Until 1871, he participated in exhibits at the National Academy and the American Watercolor Society. However, his disputatious character reasserted itself, and he came to be viewed as an outsider. As a result, he left the United States, travelling through Europe and spending several months in Palestine. In 1872, attracted by the paintings of the Düsseldorfer Malerschule, he went there to open a studio and stayed for three years.[3]

In 1875, he moved to Paris, where he also stayed for three years. This was followed by some time in London. Every so often, he visited the United States to sell his paintings. This would involve planned events, to which he invited journalists, and populist-themed lectures; attacking the established, academic art scene.

He returned to the United States in 1881 and settled briefly in Chicago, where he had friends he had helped out financially after the Great Chicago Fire. For one year, he held a teaching position in Olivet, Michigan, then moved back to New York. He died there, in his studio, in 1904.

Selected paintings

Edinburgh Castle After the Storm

Edinburgh Castle After the Storm Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives

Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives The Sea Rescue

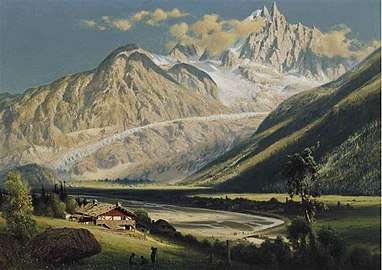

The Sea Rescue Alpine Landscape with River

Alpine Landscape with River

References

- Eduard Maria Oettinger: Moniteur des dates. Biographisch-genealogisch-historisches Welt-Register. Ludwig Denicke, Leipzig 1869, pg. 70 (Google Books)

- Thomas P. Lowry: Curmudgeons, Drunkards and Outright Fools. Courts-Martials of Civil War Union Colonels. University of Nebraska Press, 1997 ISBN 978-0-8032-8024-3 pgs.141–143 (Google Books)

- Bettina Baumgärtel, Sabine Schroyen, Lydia Immerheiser, Sabine Teichgröb: "Verzeichnis der ausländischen Künstler und Künstlerinnen. Nationalität, Aufenthalt und Studium in Düsseldorf". In: Bettina Baumgärtel (Ed.): Die Düsseldorfer Malerschule und ihre internationale Ausstrahlung 1819–1918. Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86568-702-9, Vol.1, pg. 430

Further reading

- The Works of James Fairman. In: The Art Journal. London 1880, pgs.234–236 (Online).

- Hermann Alexander Müller: Biographisches Künstler-Lexikon. Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, Leipzig 1882, pg.167 (Online).

- "James Fairman". In: Gerald M. Ackerman: American Orientalists. ACR Édition, Courbevoie/Paris 1994, ISBN 2-86770-078-7, pgs.76–81 (Google Books).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Fairman. |

- Biography @ Find a Grave

- Biography @ Questroyal Fine Art

- More works by Fairman @ the American Gallery

- More works by Fairman @ ArtNet