Jagdgeschwader II

Jagdgeschwader II (Fighter Wing II, or JG II) was the Imperial German Air Service's second fighter wing. Established because of the great success of Manfred von Richthofen's preceding Jagdgeschwader I wing, Jagdgeschwader II and Jagdgeschwader III were founded on 2 February 1918. JG II was assigned four squadrons nominally equipped with 14 aircraft each. The new wing was supposed to be fully operational in time for an offensive slated for 21 March 1918. Named to raise and lead it was 23-victory flying ace Hauptmann Adolf von Tutschek. However, he was killed in action on 15 March 1918.

| Jagdgeschwader II | |

| Active | 2 February 1918 |

|---|---|

| Disbanded | 13 November 1918 |

| Country | Germany |

| Allegiance | German Empire |

| Branch | Luftstreitkräfte |

| Colors | Jagdgeschwader II: Royal blue fuselages/tailplanes Jagdstaffel 12: White cowlings Jagdstaffel 13: Green cowlings Jagdstaffel 15: Scarlet cowlings Jagdstaffel 19: Yellow cowlings |

| Engagements | Operation Michael, Third Battle of the Aisne, Second Battle of the Marne, Amiens Offensive, Battle of Saint-Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne Offensive |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Fighter | Pfalz D.III Albatros D.V Fokker Dr.I Siemens-Schuckert D.III Fokker D.VII Siemens-Schuckert D.IV |

His hasty replacement was 28-victory ace Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold. Grounded by wounds that rendered him narcotic-dependent, the Pour le Merite winner nevertheless firmly took charge. Under his leadership, JG II advanced 40 miles (64 kilometers) behind the German offensive. As the ground fighting stalled in early April, air fighting above it intensified. Then, on the night of 12/13 April 1918, a surprise artillery bombardment put 25 of the wing's aircraft—and by extension, the wing—out of action for three weeks. By 26 May, the shortage of available aircraft had grounded two squadrons, and fuel and lubricant supplies began to dwindle. On 28 May, to encourage his wing, Berthold again began flying combat missions despite his poor physical condition. Throughout June and July, shipments of aircraft arrived—new Fokker D.VIIs, unreliable Siemens-Schuckert D.IIIs, and worn Fokker Triplanes. On 14 July 1918, the wing finally standardized on Fokker D.VIIs, just in time for the final German offensive.

Intruding French and British formations became larger, more elaborate, harder for JG II to combat. Fresh new American air units began to appear. The Allies launched their final offensive on 8 August, including a huge effort by the Royal Air Force. On 10 August, Berthold scored the last of his 16 victories for the wing, and was then shot down and hospitalized. After his departure, the wing's supplies continued to decline and experienced aces were falling while replacements were scarce. By 12 September, the balance of power had so shifted that the Imperial German Air Service could only muster about 70 fighters at Saint Mihiel to oppose almost 1,500 Allied aircraft. Although the wing fought on, and sometimes had its highest scoring days during September 1918, the scale of the Allied air effort rendered these successes negligible. The wing's fighting abilities ebbed; an Allied formation of 150 bombers on 9 October took a single loss.

On 1 November 1918, Jagdgeschwader II retreated to its final base at Carignan. By the time its final victim had been shot down on 6 November, it had tallied at least 339 confirmed aerial victories. When the war ended on 11 November 1918, the wing's personnel began to straggle back to Germany. On 13 November 1918, Jagdgeschwader II was dissolved.

Operational history

Foundation

Jagdgeschwader II (Fighter Wing II, or JG II) was created because Manfred von Richthofen's Jagdgeschwader I demonstrated the advantages of massed fighter air power. The German General Staff decided to establish two more fighter wings. They were planning a mid-March offensive, and wanted to back each of the three attacking Armees with a fighter wing.[1] Thus Jagdgeschwader II was founded on 2 February 1918 in the 7th Armee sector of the Western Front.[note 1][2]

Appointed to organize and command the new wing was Pour le Merite winner Hauptmann Adolf Ritter von Tutschek, whose aerial victory tally stood at 23 victories. Four existing fighter squadrons with a theoretical strength of 14 aircraft each were designated to form the new fighter wing—Jagdstaffeln 12, 13, 15, and 19.[2] The new wing was placed under direct control of army headquarters and was being prepared to support a spring offensive. Its four squadrons were ordered to concentrate in the vicinity of Marle, France.[3] This placed them opposite the seam in the Allied lines where British and French armies met.[4] They were underequipped with Pfalz and Albatros scouts, but began to receive Fokker Dr.1 triplanes on 16 February.[3]

Tutschek commanded Jagdstaffel 12 (Jasta 12) when JG II was founded. As he acquired staff members for his nascent wing, he assigned them to Jasta 12, making it the Stab Staffel or headquarters squadron of the wing. Tutschek flew the new wing's first combat patrol on 13 February. On 18 February, he tested one of the new triplanes. He also began to circulate among his squadrons to make himself known.[5]

Into battle

Jagdstaffel 13 (Fighter Squadron 13, or Jasta 13) led JG II into combat, scoring the new wing's first victory on 17 February 1918. Three days later, it suffered the new wing's first casualty, as the jasta Staffelführer (Commanding Officer) was killed in a takeoff accident.[6] Nevertheless, during the runup to the German spring offensive, JG II continued to score as its commander led from the front. On March 6, Tutschek downed his 27th foe, raising the wing's score to 18. However, on 15 March 1918, Adolf Ritter von Tutschek was killed in action.[7][8]

With JG II tasked to support 18th Armee, and only six days remaining until the offensive kicked off, replacement of the JG II commander was crucial. Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold, a Pour le Merite winner credited with 28 victories was appointed to the post.[note 2] His appointment was problematic. The battered and narcotic-dependent hero was still recovering from his latest wound and his second near-death hospitalization; his paralyzed infected right arm was in a sling.[note 3] Although he could not fly because his recuperation was incomplete, he had talked a doctor into returning him to his dual command of Jagdstaffel 18 (Jasta 18) and Jagdgruppe 7 (Hunting Group 7) on 1 March 1918. On 10 March, his best friend, Hauptmann Hans-Joachim Buddecke, was killed in action while under his command. A grieving, ill, and addicted grounded pilot was appointed to command of a wing of fliers on the eve of a huge offensive.[7][9]

The Berthold swap

Berthold wanted to trade what had been his Jagdstaffel 18 (Jasta 18) for one of the Jagdstaffeln of JG II, so that he would have command of a unit with which he was familiar. He was refused. He then immediately chose Jagdstaffel 15 (Jasta 15) as his Stab Staffel (headquarters squadron). It was customary for an incoming commander to bring along two or three staff members from his old unit to his new one. Berthold did just that, on March 19, 1918.[10] Then, on 20 March, Berthold stretched this custom to swap a large number of pilots from Jasta 18 to Jasta 15 – this did not include Leutnant der Reserve August Raben, as his orders had him doing the reverse, as he transferred in from Jasta 15 to take command of Jasta 18 a few days before the "Berthold swap" was to occur, with Raben assuming command of Jasta 18 as an independent squadron on 14 March 1918.[11] Berthold also added a contingent of maintenance crew from the earlier ground staff of his "old" Jasta 18 unit. The large number of transferred personnel between Jasta 15 and Jasta 18 effectively made for a unit trade, even if the jagdstaffeln numbers did not change. The day before the spring offensive, JG II was ready for battle.[7] Berthold had moved in with his Pfalz D.III.[12] However, his newly arrived pilots did not have time to upgrade to their new Fokker Dr.Is. They would go into battle in their old machinery.[13]

Operation Michael

Preliminary orders for JG II charged them with gaining aerial dominance on the left flank of the scheduled attack. The German spring offensive was launched on 21 March 1918, in a heavy fog that restricted air operations. On 22 March, Berthold gave the eulogy for Buddecke in Berlin. When Berthold returned to his command on 23 March, a victory-less JG II was being ordered to "deploy all available forces immediately". For the latter part of March 1918, the wing did just that as it fought the Allied fighters and followed the advancing German assault troops. As the ground attack sputtered into a stalemate, JG II moved forward 40 miles (64 km) after eight days to occupy the former British airfield of Balâtre.[14]

April 1918 saw an attempt by the Germans to restart their offensive, with its aim of splitting apart the French and British armies. As the ground combat churned on through the evening of the 5th, the fighting above it intensified. JG II continued to fight and down enemy aircraft and observation balloons. In turn, British bombers ineffectively struck Balâtre on several occasions. Also, on 10 April, Jasta 13 lost its commander; Leutnant Walter Göttsch was killed in action.[15]

Bombardment

Several other jagdstaffelln shared Balâtre with JG II; there were a total of about 150 German aircraft quartered on the field. However, an Allied high altitude air raid at noon on 11 April did little to discomfit the Germans.[16]

On 12 April, just after "lights out" at 2230 hours, the first shells hit Balâtre. As a French artillery spotter circled overhead calling the shots, the men of JG II sought cover in bunkers and slit trenches. By bombardment's end at 0530 hours of 13 April, some 200 shells had raked the airfield. Although JG II suffered no fatalities, it had 25 aircraft destroyed or damaged; its hangars, barracks, and maintenance facilities were also much damaged by fire and explosion. The wing was basically out of action for the next three weeks.[17]

Lull in air activity

During this quiet spell, Berthold wrote a letter home on 25 April 1918. He stated his determination to fly again. He also confided his suspicions that three of his squadron commanders were plotting his removal from command of the wing. By the end of May, all of JG II's squadrons except Jagdstaffel 19 (Jasta 19) had new Staffelführern (squadron commanders).[18]

Berthold also fulfilled a request from 18th Armee headquarters for an appreciation of the new wing's operations. His 28 April memorandum delineated the differences between the earlier ad hoc Jagdgruppe and the more recent Jagdgeschwader. The Jagdgruppe, consisting of several squadrons temporarily grouped together, concentrated its efforts on shielding nearby German reconnaissance and artillery direction two-seaters from Allied attacks. On the other hand, an Armee headquarters could launch a Jagdgeschwader anywhere along the Armee's front to counterattacking Allied flights, whether fighters or bombers. Berthold proposed having air defense officers trail along with the front-line infantry to report incoming enemy aircraft to JG II. He also asked for, and received, sufficient motor transport for JG II to quickly shift bases as it followed the ground fighting.[19]

On 8 May, Berthold's aggressive leadership led to him being entrusted with deploying all of the fighter aircraft attached to 18th Armee.[20] Indeed, by 20 May, JG II had 57 confirmed victories while in support of Operation Michael. However, on 26 May, Jasta 12 and Jasta 19 were both grounded for lack of aircraft. And, by late May, the new Siemens-Schuckert D.IIIs supplied to the wing had been returned to their factory for modification. Their departure left the already understocked wing very short of serviceable aircraft, but the Siemens-Schuckert D.IIIs were experiencing engine failures in as little as seven hours running. Their Siemens-Halske Sh.III 11 cylinder counter-rotary engines were lubricated with synthetic castor oil, and failing for lack of actual, organic-base castor oil.[21]

Berthold's return

On 27 May, the depleted JG II was detailed to cover the start of the Aisne Offensive with high altitude patrols against invasive Allied aircraft, ending in trench strafing. On 28 May, Rudolf Berthold returned to the air. He had acquired a new Fokker D.VII, and thought he could fly it because of its sensitive controls. He promptly scored his 29th victory while ignoring the pain of his festering arm. The success left him feeling he had gained additional control over his unit. He could now demonstrate his adherence to his iron code of combat to his pilots. He insisted that none of his pilots could turn back for engine trouble, jammed guns, or depletion of ammunition.[22]

Despite JG II's boost in morale at Berthold's return, the increasingly hot summer weather degraded aircraft readiness. Jasta 15 had been fitted with new Fokker D.VIIs. However, Jasta 12's lack of replacement Fokker Triplanes took them out of action for a while, and Jasta 13 was crippled. When replacement aircraft did show up for Jasta 12, they were 10 old used Triplanes instead of new Fokker D.VIIs.[23]

With fuel and oil in short supply, JG II seldom flew as an entire wing. Customarily, one jasta flew, one sat ready, and the others rested. Finally, in early June, Jasta 13 was half-equipped with new Fokker D.VIIs. However, by mid-June, Jasta 19 still was not fully equipped with Fokker D.VIIs, and Jasta 12 still flew a complement of Triplanes. There were even some Albatros D.Vs still in service with the wing.[24]

On 12 June 1918, the JG II Triplanes were grounded. Each jasta was now restricted to a monthly ration of 14,000 liters of fuel and 4,000 liters of oil. The scarce fuel and lubricants usually went to the newer and more effective Fokker D.VIIs.[25]

On 19 June, Jagdstaffeln 12 and 19 were again grounded for lack of airplanes. However, new Fokker D.VIIs began to arrive. Jasta 13 and half of Jasta 19 were issued the new planes. Any Triplanes they had were passed along to Jasta 12, but to no avail. They were forced to surrender all Triplanes as unserviceable on 24 June. On 28 June, 20 Fokker D.VIIs arrived and were split between Jagdstaffeln 12, 15, and 19.[26]

By now, Berthold was the leading surviving German ace, with 37 victories. Flying in agony as his wounded arm deteriorated, using only one hand, he was still an effective air fighter, but he welcomed rainy day groundings as a chance to recoup. Meanwhile, Jagdstaffeln 13 and 15 were involved in massive dogfights over Chemin des Dames almost every evening in late June.[27]

JG II now faced an invisible foe—influenza. On 6 July, all but three pilots of Jasta 19 were too ill to fly. However, Jasta 13 was still operational. In the runup to yet another offensive, JG II moved forward to a new base at Leffincourt. On 14 July 1918, JG II received 20 new Fokker D.VIIs; once these were parceled out, the wing was finally equipped with a single type of fighter.[28]

The last German offensive

As German troops moved into their assault on 15 July 1918, JG II was assigned to ground attack duties. Finding no worthwhile ground targets, the German fliers engaged enemy aircraft instead. By the 17th, ground combat was stalemated. As Allied aircraft struck the bridges over the Marne River, French aircraft waged a huge air battle against the German pilots. The following day, the counter-attack began. By now, JG II was supporting three German Armees—the 1st Armee, the 3d Armee, and the 7th Armee. On 20 July, the wing responded with a record 100 combat sorties flown. However, by 22 July, the last German offensive was finished; the Germans withdrew from the Marne.[29]

French air tactics changed. Their Breguet 14 B2 bombers were now shepherded by Caudron R.11 gunships; a screen of SPAD fighters would rove outside the formation to meet German attacks. The shift began on 22 July, when 30 Germans, including Jasta 19, attacked a French formation of 50.[30]

On 24 July, JG II moved to Chéry-lès-Pouilly to support 9th Armee. They received several modified Siemens-Schuckert D.IIIs and Siemens-Schuckert D.IVs. As Berthold scored his 40th victory, JG II began to face fresh American fliers newly committed to combat.[31]

Berthold's departure

On 8 August 1918, the Allies launched the Amiens offensive, which included a massive effort by the Royal Air Force. On the 9th, JG II shifted to support 18th Armee. The following day, when 12 British DeHavillands bombed railway logistics at Equancourt and Perrone at 1220 hours, the German aerial force that attacked them included JG II. In turn, Bristol F.2 Fighters from No. 48 Squadron RAF and two flights from No. 56 Squadron RAF counter-attacked. In the turmoil of combat, Rudolf Berthold shot down two British aircraft before being himself downed. He survived the crash, but his right arm was again smashed. German infantry evacuated him to hospital.[32]

On 11 August, Jasta 19 intercepted a huge force of about 100 Breguet bombers flying in formations of eight to ten planes. In the fighting, JG II lost its leading surviving ace when Leutnant Hans Martin Pippart fell. On the 12th, Berthold unexpectedly returned from hospital and insubordinately regained command. He then fell into sickbed with a fever. On 13 August, he was relieved of his command and ordered back to hospital by Kaiser Wilhelm II, never to return to combat.[33]

On 23 August, JG II's war diary gave a breakdown of aerial victories between 21 March and 21 August 1918. Jasta 12 was credited with 24 victories; Jasta 13 with 65; Jasta 15 with 83; Jasta 19 with 30. The wing's total was 202 confirmed victories, with French victims predominating.[34]

Combating the Americans

On 31 August 1918, JG II received a new commander, 21 victory ace Oberleutnant Oskar Freiherr von Boenigk. After the wing moved three times in quick succession, it settled in near the front lines at Giraumont and Doncourt by early September. They were now positioned to intercept Allied bombing missions into Germany.[35]

On 12 September, Colonel Billy Mitchell of the United States Army Air Service mounted an enormous air offensive of almost 1,500 aircraft to support the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. To oppose this incursion, the Germans had about 213 aircraft; a few more than 70 were fighters, with JG II fielding a significant number of those. Despite foul weather, the wing downed nine attacking aircraft with no loss. The next day, they downed nine more, with a single loss. On 14 September, JG II had a record day—19 aerial victories, with only a single German pilot lost to captivity. Jasta 15 celebrated its 150th victory overall.[36]

On 15 September, the American assault ground to a halt. The aviation highlight of the day was the Jasta 15 attack on the incoming No. 104 Squadron RAF. Only five of the 12 British Airco DH.9s returned to their base. A day later, the American air casualties included an entire flight of four from the American 96th Aero Squadron. Two inexperienced squadrons of the American First Day Bombardment Group also suffered heavy casualties. On 18 September, Jasta 12 brought down five of six American attacking bombers only three kilometers from the jasta's home airfield. However, by 23 September, supply shortages began to cramp the wing's effort. The individual jagdstaffeln were limited to 450 liters of fuel daily, only a fifth of the squadron's daily need.[37]

.jpg)

September's German victories in the air had little influence on the fighting. Nor did the aerial battles entirely favor the Germans. On the Allied side, there was a drive to destroy or burn the German observation balloons, thus blinding the German army.[38] Balloon busting French ace Lieutenant Maurice Boyau shot down his final four balloons.[39] The American team of Lieutenant Frank Luke and First Lieutenant Joseph Wehner shot down nine balloons in the five days.[40] Overwhelming formations of Allied aircraft successfully executed their missions. The battle-hardened pilots of Jadgdeschwader II extracted a high blood cost from the American rookies in September 1918, to no real effect.[41]

The end

On 26 September 1918, the First United States Army began their offensive. They were supported by 800 Allied aircraft; about three-fourths of these were American. JG II shot down 14 American planes that day. As the fighting continued, the wing redeployed for better tactical position on the evening of 28 September. Boenigk left the wing for leave, as Josef Veltjens returned from his to take command.[42]

As the battle continued, the Americans pushed fresh ground troops into the attack on 4 October. As the air combat raged, on 9 October the wing destroyed its first enemy observation balloon in more than six weeks. On that same day, a massive formation of 150 Allied two-seater aircraft crossed the German lines, and only one of them fell to the wing.[43] The overwhelming weight of enemy numbers, plus the dwindling supply of essential fuel, lubricants and aircraft engines, was grinding the wing down.[44]

As the fighting raged through October, JG II's personnel began to lose heart. News of peace negotiations for ending the war were being leaked to them. So was information about the soldier's revolutionist councils burgeoning in the German military. There was even news of mutinies in the High Seas Fleet. The wing also lost experienced aces during the month, such as Leutnant Olivier Freiherr von Beaulieu-Marconnay, Vizefeldwebel Albert Haussmann, and Vizefeldwebel Gustav Klaudat, at a time when replacements were scarce. The wing fought on. On 22 October, Jasta 13 scored what turned out to be its last victories, bringing the squadron total to 150. On 25 October, the German lines began to give way. Jasta 12 scored seven victories on the last two days of October.[45]

On 1 November 1918, the wing began to withdraw to Carignan. On 3 November, Jasta 12 scored six victories, and Jasta 19 scored twice. That same day, JG II began a further retreat, to Florenville. On the 4th, Georg von Hantelmann shot down a SPAD for the final victory for Jasta 15. On 6 November, Jasta 19 scored the final victory for the wing, shooting down an American SPAD. Jagdeschwader II was credited with at least 339 confirmed victories. In turn it had suffered 18 pilots killed in action, four more killed in flying accidents, eight taken prisoner, and eight either injured or wounded in action, for a total casualty count of 38.[46]

When the Armistice took effect on 11 November 1918, the wing's personnel began the journey home by vehicle or foot. On 13 November, stragglers from JG II gathered at Halle an de Salle to be officially demobilized as the wing was dissolved.[47]

Commanding officers

(Interim commanders are marked @)

- Hauptmann Adolf Ritter von Tutschek: 1 February—15 March 1918[48]

- Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold: 18 March—10 August 1918

- @Hauptmann Hugo Weingarth: 10 August—12 August 1918

- @Rittmeister Heinz Anton von Brederlow: 12 August 1918

- Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold: 12 August—13 August 1918

- @Leutnant Josef Veltjens: 13 August—31 August 1918

- Oberleutnant Oskar Freiherr von Boenigk: 31 August—28 September 1918

- @Leutnant Josef Veltjens: 28 September—12 October 1918

- Oberleutnant Oskar Freiherr von Boenigk: 12 October—25 October 1918

- @Oberleutnant Fritz Krapfenbauer: 25 October—2 November 1918

- Oberleutnant Oskar Freiherr von Boenigk: 2 November—11 November 1918[49]

Notable members

Among the pilots of Jagdgeschwader II were the following honorees for their acedom.

- Leutnant Franz Büchner won 38 of his 40 victories while with JG II, and was awarded the Pour le Merite.[50]

- Leutnant Ulrich Neckel won 30 victories in Jasta 12—26 with the wing—and the Pour le Merite.[51]

- Leutnant Olivier Freiherr von Beaulieu-Marconnay shot down 25 enemy aircraft while with JG II and won the Pour le Merite.[52]

- Leutnant (later Colonel) Josef Veltjens scored 25 of his 35 victories with JG II and won the Pour le Merite.[53]

- Leutnant Hermann Becker achieved 20 of his 23 victories in the wing, and was awarded the House Order of Hohenzollern.[54]

- Pour le Merite awardee Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold scored 16 of his 44 victories while leading JG II.[55]

- Leutnant Johannes Klein had 16 victories with JG II, winning the Hohenzollern.[56]

- Leutnant Hans Martin Pippart had 16 of his 22 victories with JG II, and received the Hohenzollern.[57]

- Leutnant Georg von Hantelmann shot down 15 enemy aircraft for the wing and won the Hohenzollern.[58]

- Vizefeldwebel Gustav Klaudat shot down six enemy aircraft and gained the Iron Cross.[59]

- Oberleutnant (later General-major) Oskar Freiherr von Boenigk won the last five of his 26 victories with JG II, as well as the Pour le Merite.[60]

Aircraft inventory

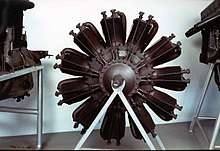

.jpg)

The squadrons being consolidated into the fighter wing were equipped with Pfalz and Albatros fighters.[5]

The pilots transferring into Jasta 15 from Jasta 18 on 20 March 1918 brought their airplanes with them. The squadron livery of their aircraft was based on the uniform color of Berthold's old cavalry unit. It consisted of a royal blue fuselage and scarlet engine cowling. Their Fokker Dr.I triplanes would later carry the same color scheme.[61] The other three squadrons of JG II copied the blue fuselages. However, Jasta 12 had white cowlings. Jasta 13 elected hunter green. The cowlings of Jasta 19 aircraft were white.[62]

On 6 April 1918, nine Siemens-Schuckert D.IIIs were added to JG II's inventory. Much was expected of these craft because they were the fastest climbing planes the German pilots had yet seen. [63]

The bombardment of their airfield on 12/13 April took 25 aircraft out of operation.[64]

By the end of May, engine failures caused withdrawal of the Siemens-Schuckert D.IIIs, depleting an already under-strength wing inventory. On 26 May, Jadgstaffeln 12 and 19 were grounded for lack of aircraft. However, the wing began to receive a mixture of new Fokker D.VIIs and 10 worn Fokker Dr.Is as replacements. The wing even had some Albatros D.Vs still in stock.[65]

By 19 June 1918, Jadgstaffeln 12 and 19 were again grounded for lack of airplanes. Then re-equipment of Jasta 13 and Jasta 19 began; as they got their new Fokker D.VIIs, they passed on Fokker Dr.Is to Jasta 12. On 24 June, all Fokker Dr.Is were removed from the wing, leaving Jasta 12 with four unusable Siemens-Schuckerts.[12] When 20 new D.VIIs arrived on 28 June, the six with BMW engines were posted to Jasta 15 with the others divided between Jasta 12 and Jasta 19.[26]

On 14 July 1918, JG II finally standardized on a single mark of aircraft when it received 20 more replacement Fokker D.VIIs. On 24 July, several of the modified Siemens-Schuckerts were returned to the wing.[66]

See also

- Jagdstaffel 18, Rudolf Berthold's old command and August Raben's new one

Footnotes

- Jagdgeschwader III was founded simultaneously with JG II; its founding squadrons were Jagdstaffeln 2, 26, 27, and 36.

- Berthold had been advocating the concept of a fighter wing since January 1917, and he had been importuning the General Staff for a wing command.

- Berthold's medical history up to March 1918:

June 1915: Dysentery

10 February 1916: Wounded hand

25 April 1916: Coma. Broken leg, nose, and upper jaw; transitory blindness

24 April 1917: Bullet wound right shin

10 October 1917: Ricocheting bullet pulverized his right humerus, resulting in lingering paralysis of right hand

Endnotes

- VanWyngarden (2016), pp. 6–7.

- Kilduff (2012), p. 111.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 6–8.

- Franks & Giblin (2004), p. 131.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 8.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 16.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 21–23.

- Kilduff (2012), pp. 110–112.

- Kilduff (2012), pp. 110–115.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 35–37.

- VanWyngarden (2011), p. 72.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 71–72.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 21–25.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 25–28.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 28–29.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 29.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 30–32.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 35–36.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 36.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 38.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 43–44.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 45, 50.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 45–46.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 46, 49–50, 65.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 65, 68.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 71–74.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 71, 73.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 76.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 77–78.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 78–79.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 79.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 79–80.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 82–84.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 88.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 88–90.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 90–92, 95–96.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 97–104.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 98–99.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 124–125.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 58–59, 80.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 107.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 108–109.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 109.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 114.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 110–116.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 117–118.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 118–119.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 219.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 120.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 68–69.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 173.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 68.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 222–223.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 69.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 71–72.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 145.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 180.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 123–124.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 144.

- Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 77.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 25.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 39.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 30.

- VanWyngarden (2005), p. 32.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 43–46, 49, 65.

- VanWyngarden (2005), pp. 76, 79.

Bibliography

- Franks, Norman; Bailey, Frank W. & Guest, Russell F. (1993). Above The Lines: The Aces and Fighter Units of the German Air Service, Naval Air Service, and Flanders Marine Corps, 1914–1918. London, UK: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-73-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- —, Norman; Giblin, Hal (2004). Under the Guns of the Kaiser's Aces: Böhme, Muller, Von Tutschek and Wolff: The Complete Record of Their Victories and Victims. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1904010029.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Kilduff, Peter (2012). Iron Man: Rudolf Berthold: Germany's Indomitable Fighter Ace of World War I. Oxford: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-908117-37-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- VanWyngarden, Greg (2005). Jagdgeschwader Nr II: Geschwader Berthold. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-727-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- — (2011). Osprey Elite Aviation Units #40: Jasta 18 - The Red Noses. Oxford UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-335-5.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- — (2016). Aces of Jagdgeschwader Nr III. Oxford UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-47280-843-1.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)