Jacques Bongars

Jacques Bongars (1554 – 29 July 1612) was a French scholar and diplomat.

Life

Bongars was born at Orléans, and was brought up in the Reformed faith. He obtained his early education at Marburg and Jena, and returning to France continued his studies at Orléans and Bourges. After spending some time in Rome he visited eastern Europe, and subsequently made the acquaintance of Ségur Pardaillan, a representative of Henry, king of Navarre, afterwards Henry IV of France. He entered the service of Pardaillan, and in 1587 was sent on a mission to many of the princes of northern Europe, after which he visited England to obtain help from Queen Elizabeth for Henry of Navarre. He continued to serve Henry as a diplomatist, and in 1593 became the representative of the French king at the courts of the imperial princes. Vigorously seconding the efforts of Henry to curtail the power of the house of Habsburg, he spent health and money ungrudgingly in this service, and continued his labors until the king's murder in 1610. He then returned to France, and died at Paris.[1]

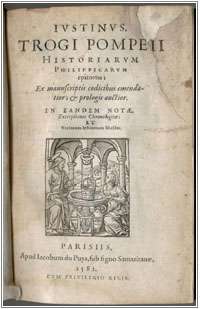

Bongars wrote an abridgment of Justin's abridgment of the history of Trogus Pompeius under the title Justinus, Trogi Pompeii Historiarum Philippicarum epitoma de manuscriptis codicibus emendatior et prologis auctior (Paris, 1581). He collected the works of several French writers who as contemporaries described the crusades, and published them under the title Gesta Dei per Francos (Hanover, 1611). Another collection made by Bongars is the Rerum Hungaricarum scriptores varii (Frankfort, 1600). his Epistolae were published at Leiden in 1647, and a French translation at Paris in 1668–1670. Many of his papers are preserved in the Burgerbibliothek at Bern, to which they were presented in 1632, and a list of them was made in 1634. Other papers and copies of instructions are now in several libraries in Paris; and copies of other instructions are in the British Museum.[1]

Notes

-

References

- H. Hagen, Jacobus Bongarsius; ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der gelehrten Studien des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts (Berne, 1874)

- Léonce Anquez, Henri IV et l'Allemagne d'après les mémoires et la correspondance de Jacques Bongars (Paris, 1887)

- Andrist Patrick, Strassburg - Basel - Bern. Bücher auf der Reise. Das Legat der Bibliothek von Jacques Bongars, die Schenkung von Jakob Graviseth und das weitere Schicksal der Sammlung in Bern, in Berner Hans (ed.), Scriptorium und Offizin : Festgabe für Martin Steinmann zum 70. Geburtstag, Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde 110 (2010), 249-268.