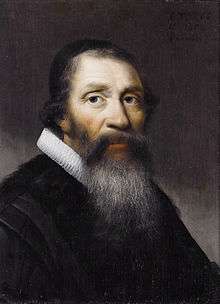

Jacobus Trigland

Jacobus Trigland (Triglandius) (22 July 1583 – 5 April 1654) was a Dutch Reformed theologian. After the Synod of Dort of 1618-19, he worked and wrote against the Remonstrants.

Life

He was born at Vianen to Roman Catholic parents. Brought up by relatives at Gouda, he was sent, in 1597, to some priests at Amsterdam to study theology. Toward the end of 1598 he went to Leuven where doubts arose in his mind which ultimately led him to break with Catholicism. He was entrusted with a mission to Haarlem by the head of the Collegium Pontificium, and never returned to Leuven. After a few weeks at Gouda, where his foster relations rejected him, he sought refuge in the house of his parents, where he studied Reformed tenets, meanwhile seeking occupation to gain his livelihood.[1]

In 1602 he was made rector of the school at Vianen, and in the following year entered the Reformed Church. Having prepared privately for the ministry, he was ordained pastor at Stolwijk in 1607; and was pastor at Amsterdam, from 1610. Here, in 1614, he became involved in affairs of Church and state which ended only with his death. In 1617 he received leave of absence to the Reformed church at The Hague, and was a deputy of the provincial synod of North Holland to the Synod of Dort, which appointed him a member of the committee to draw up the Canons of Dort.[1]

Trigland was professor of theology at the University of Leiden, succeeding André Rivet in 1633.[2] He lectured on the exegesis of the Old Testament, on the Loci Communes, 1639–50, and later on cases of conscience. He was also pastor of the Reformed church at Leiden (1637–45). He died at Leiden.[1]

Works

His Kerckelycke Geschiedenissen (Leiden 1650) was an important work on Calvinist church histories. In it he commented on the work of Johannes Uytenbogaert, who had published a Remonstrant Church History in 1646.[3] His own distinctive view traced the Protestant Reformation back to Wessel Gansfort, and claimed that the doctrine of election in Philipp Melanchthon and Heinrich Bullinger was compatible with the outcome of the Synod of Dort.[4]

Writing against the Remonstrants, his feeling was that their teachings were pernicious and not to be allowed. This is plain in his Den rechtghematichden Christen (Amsterdam, 1615). In his Verdedigingh van de Leere end' Eere der Ghereformeerde Kerken, ende Leeraren (1616) he defends Reformed dogmatics. He opposed civil intervention in ecclesiastical affairs in his Antwoordt op drij vraghen dienende tot advys in de huydendagsche kerklijke swarigheden (1615), and his Christelijcke ende nootwendighe verclaringhe (1615).[1]

Family

Cornelis Trigland, tutor to the future William III of England, was his son.[5] Another Jacobus Trigland, also a professor at Leiden, was his grandson.[6]

Notes

- http://www.ccel.org/s/schaff/encyc/encyc12/htm/ii.xii.htm

- Peter T. van Rooden, Theology, Biblical Scholarship, and Rabbinical Studies in the Seventeenth Century: Constantijn L'Empereur (1591-1648), Professor of Hebrew and Theology at Leiden (1989), note pp. 53-4.

- Willem Frijhoff, Marijke Spies, Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: 1650: Hard-won unity (2004), p. 362.

- Alastair Duke, Reformation and Revolt in the Low Countries (2003), note p. 4.

- Wouter Troost, William III the Stadholder-king: A Political Biography (2005 translation), p. 34.

- http://www.knaw.nl/publicaties/pdf/20011109_01.pdf, p. 4.

Further reading

- H. W. Ter Haar (2008), Jacobus Trigland

External links

![]()