Jacob Herreyns the Elder

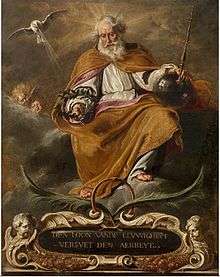

Jacob Herreyns or Jacob Herreyns (I)[1] Antwerp, baptized on 23 December 1643 – Antwerp, 1 January 1732) was a Flemish painter, printmaker and designer of tapestries.[2] He worked in Antwerp where he painted many altarpieces. He was a known staffage painter who added the figures in the landscapes of other artists.[3] As a printmaker, he produced mostly prints of mythological subjects.[4] He held also the position of 'muntmeester' (mint master) of Brabant.[5]

Life

Herreyns was born in Antwerp as son of Daniël Herreyns and Maria van de Dorp and was baptized in the cathedral of Antwerp on 23 December 1643.[5] His father was a printmaker.[6] He was registered as a pupil of the obscure painter Norbert van Herp the Elder in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke in the Guild year 1671–1672. Van Herp was a still life painter and the son of the better known Willem van Herp. In the Guild year 1671-1672 Herreyns was admitted as a master of the Guild. In the Guild year 1695-1696 Jan-Baptist Jacops and Jan Ritsaert Musketieer were registered as his pupils.[5]

He married Maria-Catharina Smout on 13 December 1677. His wife was a sister of the painters Lucas Smout the Younger and Dominicus Smout. Through this marriage he became a brother in law of the battle painter Gonzales Franciscus Casteels who married his wife's sister. Herreyns and his wife had 10 children: Daniel (II) (*25 September 1678), Maria-Catharina (*7 May 1681), Isabella-Clara (* 30 July 1683), Anna-Theresia (*24 November 1685), Jacob (II) (*25 August 1687), Susanna-Maria (*11 December 1689), Joanna (*5 August 1692), Jan-Baptist (*28 November 1695), Francis-Gonzales (* 15 October 1699) and Anna-Elisabeth (*12 October 1701). Jacob (II) became a painter and his grandson was the painter Willem Jacob Herreyns who played an important role in Flemish art and art education at the end of the 18th century. Daniel (II) also became a painter.[2]

In 1709, Herreyns and Abraham Genoels were commissioned to fit out and decorate the former tapestry as a full-fledged theatre.[7] Herreyns and his wife made a will on 14 February 1730. On 29 December 1731 Herreyns changed his will as he had become a widower and his sons Daniel II and Jacobus II were already deceased by that time.[5]

He was buried on 1 January 1731 in the Saint Andrew Church, in front of the altar of the mint masters of Brabant, of whom he had been a lifelong member.[5]

Work

Herreyns was a versatile artist. He was a painter, printmaker and designer of tapestries.[2] His altarpieces are found in various churches in and around Antwerp. He was a staffage painter who added the figures in the landscapes of other artists.[3] As a printmaker, he produced prints of mythological, religious and allegorical subjects.[4]

References

- Name variations: Jacob Herryns (I), Jacobus Aryns, Jacobus Areyns, Jacobus Herrens, Jacob Heereyns (I)

- Jacob Herreyns at the Netherlands Institute for Art History

- Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Catalogue du Musée d'Anvers, Buschmann, 1857, pp. 386-387 (in Dutch)

- Herreyns, Jacob I, the Elder or Herryns or Herrens in: Benezit Dictionary of Artists

- Ph. Rombouts and Th. van Lerius, De Liggeren en andere Historische Archieven der Antwerpsche Sint Lucasgilde, onder Zinkspreuk: "Wy Jonsten Versaemt" afgeschreven en bemerkt door Ph. Rombouts en Th. Van Lerius, Advokaet, onder de bescherming van den raed van bestuer der koninklyke Akademie van beeldende Kunsten, van gezegde Stad, Volume 2, Antwerp, 1872, pp. 409, 410, 412 (in Dutch)

- Reginald Howard Wilenski, Flemish Painters, 1430-1830, Viking Press, 1960

- Bram Van Oostveldt, The Theatre de la Monnaie and Theatre Life in the 18th Century Austrian Netherlands: From a Courtly-aristocratic to a Civil-enlightened Discourse?, Academia Press, 2000, p. 54

External links