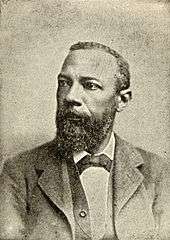

Jacob C. White Jr.

Jacob "Jake" C. White Jr. (1837 – November 11, 1902) was an American educator, intellectual, and civil rights activist. Born to a successful and influential businessman, White received the finest education afforded to African-Americans of the time and became intertwined in the dealings of Philadelphia's most prominent black leaders. The first black man in the city to be appointed as a school principal, White is recognized for his position at Roberts Vaux Consolidated School. During his tenure between 1864 and 1896, White reformed the institute and became the leading figure in the field of urban education in Philadelphia. Alongside his academic endeavors, White was significant in the sports field: he helped establish the Philadelphia Pythians, an early black baseball club. Following the shooting of his friend and fellow activist Octavius Catto in 1871, White became the top civil rights activist in the city, and remained active in the community until his death in 1902.

Biography

Early life and career

Jacob White Jr. was born to Jacob White Sr. and Elizabeth White in 1837. His brother was George Bustill White and his sister-in-law was Emilie Davis. He was raised at 100 Old York Road in Jenkintown, a predominantly white neighborhood 10 miles (16 km) from downtown Philadelphia.[1] According to an 1866 city directory, Jacob and George lived with their father at his home at 485 York Avenue.[2] His father was a barber and physician who was well-respected in the black community, formerly the owner of a china shop that sold products manufactured by free negro labor, eschewing goods produced by slave labor. A savvy businessman, White Sr. enjoyed the benefits of profitable real estate investments, becoming an eminent figure in Philadelphia's exclusive inner circle of elite blacks. White Sr. engaged in several endeavors promoting education and was a long-time abolitionist; both of his passions were passed to the young White.[3]

White was initially enrolled at the Lombardy Street Public School.[3] After completing his grammar schooling, he matriculated at the Institute for Colored Youth (ICY) in 1853. Founded by the Society of Friends (Quakers), the ICY emphasized high moral standards for its students and offered a classical study of Latin, Greek, and trigonometry.[3][4] While enrolled, White expressed an acute awareness of black society and psychological concepts in essays he presented. On May 24, 1855, he addressed Governor James Pollock at a special reception for the institute, touching on the issue of African American citizenship.[5][6] The same year, White was elected secretary of the Banneker Institute, a student instructional society that convened weekly to have scholarly discussions. White was his class's lone graduate from the ICY on May 6, 1857; he earned praise for his popularity among classmates and professors alike.[5][6]

In 1858, he accepted a teaching position at the ICY's preparatory school for boys. White furthered his interests in mathematics during his teaching stint at the institute. He became a lecturer on the subject while a member of the mathematics committee of the Banneker Institute, also becoming a proficient chess player in his leisure time.[6] His exceptional skills with figures and calculations led to different business ventures: he was an agent for the Anglo-African weekly newspaper (1860–1861) and Pine and Palm (1860–1862).[6] In 1861, he became a representative at the Haitian Bureau of Emigration, empowering him with the transfers of funds for free blacks who sought to move to Haiti, via New York. As a result of his different ventures, White became a relatively wealthy man at a young age.[6]

Long interested in an administrative role, White was the leading candidate for principal of the neglected Roberts Vaux Consolidated School. In 1864, he was appointed principal, the first black person in Philadelphia to assume such a role.[4][7][8] Originally housed in the poorly ventilated basement of the Zoar Methodist Church, under White's leadership, the Vaux school moved to the building formerly housing the William D. Helley School and tripled in attendance. White's administration facilitated the integration of the educational system in Philadelphia, including the end of segregation at Central High School and Girls' Normal School. Satisfied with his accomplishments, White retired from the position in June 1896.[9]

Philadelphia Pythians

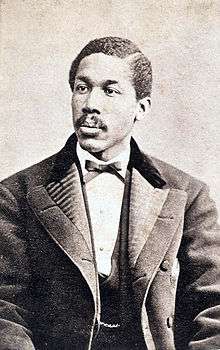

During his tenure as a teacher at the ICY, White closely collaborated with Octavius Catto, an important civil rights activist and long-time friend of White's who shared a similar social group and views on education. Both men, former cricket players at the ICY, believed baseball was another outlet for African Americans to promote social reform and prove their right for full citizenship.[10][11] In the spring of 1866, White and Catto established the Philadelphia Pythians, a baseball club composed mainly of men from the Knights of Pythias fraternal organization. Catto, a hard-hitting shortstop and second baseman, was the de facto captain on the field, while White became the team's secretary, responsible for scheduling games, arranging festivities, and recording statistics. Soon, Pythian games became a popular fixture of the black community.[12]

On September 3, 1869, the Pythians played in the first recorded interracial baseball game. "Colonel" Thomas Fitzgerald of the Philadelphia City Item, a well-respected figure in baseball and a former owner of the Philadelphia Athletics, first proposed the idea in his newspaper to seek potential contenders.[13] Their opponent, The Olympics, was Philadelphia's oldest ball club, having roots in the city dating back to 1832, playing town ball. Although the Pythians lost the contest 44–23, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the club "acquitted themselves in a very creditable manner, especially their outfielders, who made several very fine fly catches".[14]

White and Catto petitioned, albeit unsuccessfully, to join white athletic organizations. Denied opportunities to integrate, the Pythians nonetheless developed a friendly relationship with the Philadelphia Athletics.[14] The Athletics often shared their field with the team and chair member Hicks Hayhurst advocated for the integration of black ball clubs. The Pythians enjoyed several successful seasons but Catto's murder in 1871 signaled an end in team activities until their reformation for the 1887 season of the National Colored Base Ball League.[14]

Other endeavors

Following Catto's death, White became "the preeminent statesmen for Philadelphia’s African-American community", according to the Falvey Memorial Library.[5] His memberships included the National Equal Rights League, Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association of Pennsylvania, contributing as a secretary. The death of Catto, however, presaged the move of the Equal Rights Society headquarters a year later; consequently, White's interests in civil rights organizations waned.[9]

In 1849, White founded Lebanon Cemetery, one of only two cemeteries for the burial of African Americans in Philadelphia at the time. By 1889, the cemetery was overcrowded and in disrepair. A sensational trial took place after a journalist caught grave robbers from the Jefferson Medical College stealing corpses for use as cadavers by medical students. The city condemned the cemetery and relocated the bodies to Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.[15]

In June 1895, at an organizational meeting White was appointed the president of the board for the Douglass Memorial Hospital. Under his direction, he appropriated state funds for the hospital in 1898 from Alexander K. Pedrick of the State Senate. Having succeeded in procuring the funds, White resigned from his position but maintained a seat on the board until his death on November 11, 1902.[16]

References

- Silcox 1973, p. 76.

- "All's Well That Ends Well". Memorable Days: The Emilie Davis Diaries. 2012-10-05. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- Silcox 1973, pp. 76–78.

- Lane, Roger. "Jacob C. White Jr.: Behind the Marker". Explore PA History. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "Jacob C. White Jr". Villanova University. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- Silcox 1973, pp. 80–85.

- Hine, Darlene Clark; Jenkins, Earnestine (1999). A Question of Manhood: A Reader in U.S. Black Men's History and Masculinity. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253213436.

- Smith, Courtney Michelle (2016-12-28). Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia. McFarland. ISBN 9781476627434.

- Silcox 1973, pp. 88–90.

- Whirty, Ryan (2015). "Philadelphia's Pythians Made History in 1800s". Philly.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- Grigsby 2010, pp. 30–32.

- Silcox 1973, pp. 86–87.

- Casway, Jerrold. "September 3, 1869: Inter-racial baseball in Philadelphia". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "The Pythian Base Ball Club: Political Activism on the Diamond". Villanova University. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "Historic Eden Cemetery - Eden Stories". www.edemcemetery.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Silcox 1973, pp. 96–97.

Bibliography

- Grigsby, Daryl Russell (2010). Celebrating Ourselves: African-Americans and the Promise of Baseball. Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 9781608447985.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silcox, Harry C. (January 1973). Philadelphia Negro Educator: Jacob C. White Jr. 1837–1902. 97. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)