Knucklebones

Knucklebones, also known as Astragalus, Tali, Fivestones, or Jacks, is a game of ancient origin, usually played with five small objects, or ten in the case of jacks. Originally the "knucklebones" (actually the astragalus, a bone in the ankle, or hock[1]) were those of a sheep, which were thrown up and caught in various manners. Modern knucklebones consist of six points, or knobs, projecting from a common base, and are usually made of metal or plastic. The winner is the first player to successfully complete a prescribed series of throws, which, though similar, differ widely in detail. The simplest throw consists in either tossing up one stone, the jack, or bouncing a ball, and picking up one or more stones or knucklebones from the table while it is in the air. This continues until all five stones or knucklebones have been picked up. Another throw consists of tossing up first one stone, then two, then three and so on, and catching them on the back of the hand. Different throws have received distinctive names, such as "riding the elephant", "peas in the pod", "horses in the stable",[2] and "frogs in the well".

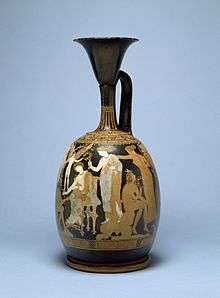

_-_Knucklebones.jpg)

History

Talus bones of hoover animals also known as astragali are found in archaeological excavations related to the period starting from 5000 B.C. much more frequently than other bones. Astragalus, being almost symmetric, has only four sides on which it may rest and is an early example of the game of chance. Knucklebones are believed to be an early precursor of the dice. In contrast to the dice, the astragalus is not entirely symmetric with the broad side having a chance ~0.38 and the other side having a chance ~0.12.[3]

Sophocles, in a written fragment of one of his works, ascribed the invention of knucklebones to the mythical figure Palamedes, who taught it to his Greek countrymen during the Trojan War. Both the Iliad and the Odyssey contain allusions to games similar in character to knucklebones. Pausanius in his Description of Greece (2.20.3) tells of a temple of Fortune in Corinth in which Palamedes made an offering of his newly invented game.[2] Children's games upon Mount Ida, gave him Eros for a companion and golden dibs with which to play. He even condescended to sometimes join in the game (Apollonius). It is significant, however, that both Herodotus and Plato ascribe a foreign origin to the game. Plato, in Phaedrus, names the Egyptian god Thoth as its inventor, while Herodotus relates that the Lydians, during a period of famine in the days of King Atys, originated this game and indeed almost all other games,[2] with the exception of draughts.[4]

There were two methods of playing in ancient times. The first, and probably the primitive method, consisted in tossing up and catching the bones on the back of the hand, very much as the game is played today. In ancient Rome, it was called tali (knucklebones): a painting excavated from Pompeii, currently housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, depicts the goddesses Latona, Niobe, Phoebe, Aglaia and Hileaera, with the last two being engaged in playing a game of knucklebones. According to an epigram of Asclepiodotus, astragali were given as prizes to schoolchildren. This simple form of the game was generally only played by women and children, and was called penta litha or five-stones. There were several varieties of this game besides the usual toss and catch; one being called tropa, or hole-game, the object of which was to toss the bones into a hole in the earth. Another was the simple game of odd or even.[2]

The second, probably derivative, form of the game was one of pure chance, the stones being thrown upon a table, either from the hand or from a cup, and the values of the sides upon which they fell were counted. The shape of the pastern bones used for astragaloi as well as for the tali of the Romans, with whom knucklebones was also popular, determined the manner of counting.[2]

.jpg)

The pastern bone of a sheep, goat, or calf has two rounded ends upon which it cannot stand and two broad and two narrow sides, one of each pair being concave and one convex. The convex narrow side, called chios or "the dog", was counted as 1, the convex broad side as 3, the concave broad side as 4, and the concave narrow side as 6.[2]

Four astragali were used and 35 different scores were possible in a single throw. Many of these throws received distinctive names such as: Aphrodite, Midas, Solon, and Alexander. Among the Romans, some of the names were: Venus, King, and Vulture. The highest throw in Greece counted 40, and was called the Euripides. It was probably a combination throw, since more than four sixes could not be thrown at a single time. The lowest throw, both in Greece and Rome, was the Dog.[2]

Modern game

The modern game may use a rubber ball, and the knucklebones (jacks), typically a set of ten, are made of metal or plastic. There are variants of how the players decide who goes first: it is usually through "flipping" (the set of jacks is placed in cupped hands, flipped to the back of the hands, and then back to cupped hands again; the player who keeps the most from falling goes first), but may be via ip dip, or eeny, meeny, miny, moe, or a variant thereof. To set up the game, the jacks are scattered loosely into the play area. The players in turn bounce the ball off the ground, pick up jacks, and then catch the ball before it bounces for a second time.

The number of jacks to be picked up is pre-ordained and sequential; at first one must be picked up ("onesies"), next two ("twosies"), and so on, depending on the total number of jacks included. The number may not divide evenly, and there may be jacks left over. If the player chooses to pick up the leftover jacks first, one variation is to announce this by saying "horse before carriage" or "queens before kings". The playing area should be decided between the players since there is no official game rule regarding that.

The winning player is the one to pick up the largest number of jacks, and the game can be made more challenging by playing with fifteen or twenty jacks (two sets). Regardless of the total number of jacks in play, the player who gets to the highest game wins. Game one is usually single bounce (onesies through tensies); game two is chosen by whoever "graduates" from game one first, and so on. Some options for subsequent games are "double bounces", "pigs in the pen", "over the fence", "eggs in the basket" (or "cherries in the basket"), "flying Dutchman", "around the world", etc. Some games, such as "Jack be nimble", are short games which are not played in the onesies-to-tensies format.

Variations

A variation, played by Israeli school-age children, is known as kugelach or Chamesh Avanim (חמש אבנים, "five rocks"). Instead of jacks and a rubber ball, five die-sized metal cubes are used. The game cube is tossed in the air rather than bounced.[5] There's also the Korean game Gonggi, another variant. Also in middle east, like Turkey and Iran, there is a similar game cal "ye qol do qol" .[6]

See also

References

- FN David. Games, Gods and Gambling: A history of probability and statistical ideas. London: Charles Griffin & Co., 1962. rpt New York; Dover, 1998. p 2.

-

- Maistrov, L.E. (1967). Probability Theory: A Historical Sketch. Academic Press, Inc.

- Herodotus, The Histories, Book I: 94

- Abandon All Hope Ye Who Enter Here

- "یک قل دو قل - ویکیپدیا، دانشنامهٔ آزاد". fa.m.wikipedia.org. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Jack-Stones. |

- Statistical analysis of knucklebone throws

- Another statistical analysis of knucklebone throws