Jackson Mine

The Jackson Mine is an open pit iron mine in Negaunee, Michigan, extracting resources from the Marquette Iron Range. The first iron mine in the Lake Superior region,[3] Jackson Mine was designated as a Michigan State Historic Site in 1956[2] and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.[1] The Lake Superior Mining Institute said, the mine "is attractive in the iron ore region of Michigan and the entire Lake Superior region, because of the fact it was here that the first discovery of iron ore was made, here the first mining was done, and from its ore the first iron was manufactured."[4] Multiple other mines soon followed the Jackson's lead, establishing the foundation of the economy of the entire region.[2] The mine is located northwest of intersection of Business M-28 and Cornish Town Road.

Jackson Mine | |

North Jackson Pit No. 1, 2010 | |

| |

| Nearest city | Negaunee, Michigan |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 46°29′55″N 87°37′22″W |

| Area | 1 acre (0.40 ha) |

| Built | 1848 |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000414[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 03, 1971 |

| Designated MSHS | February 18, 1956[2] |

Origins of the Jackson Mine (1844–1847)

In 1844, government surveyor Douglass Houghton tasked his deputy, William A. Burt,[5] with leading a party into Michigan's Upper Peninsula to carry out a full survey of the land.[6] On September 19, 1844, Burt noted odd compass fluctuations while surveying in the area of Teal Lake (near present-day Negaunee, Michigan).[2][7] He asked his men to investigate, and they discovered rock outcroppings that proved to contain iron ore, later known as the Marquette Iron Range.[2] Although the local Ojibwe people (Chippewa) and earlier Native Americans certainly knew of these ore deposits, Burt and Houghton noted the find in their reports, and were the first to publish this discovery to the world at large.[5]

In June 1845, businessmen organized the Jackson Mining Company in Jackson, Michigan, with Abram V. Berry as president and Philo M. Everett as treasurer.[5][7] The company was interested in starting a copper mine in the Upper Peninsula; it secured a lease for that purpose and sent a prospecting party, led by Everett, to the Upper Peninsula.[6] Arriving in Sault Ste Marie, they met French Canadian Louis Nolan, who knew of Burt's discovery the year before.[7] While not secret, the find was not generally known.[5] Everett expressed interest in the iron, and Nolan guided the party to the mouth of the Carp River (the location of present-day Marquette) and on to Teal Lake, but was unable to find the correct location.[5] The party continued onward to Copper Harbor, where they fell in with Chippewa chief Marji-Gesick, who was familiar with the Teal Lake area.[5] Marji-Gesick guided the party to the right area and showed Everett iron ore in the roots of a fallen tree.[2] The Jackson Mine was developed here. The stump of this tree was preserved for its historical importance until it burned in 1900,[8] even so the tree was symbolically included in the seal of the city of Negaunee.[6] Everett registered a claim to the site and had samples of the ore assayed; the ore proved to be of high quality, specifically hematite with a small percentage of manganese and chromium.[2] The Jackson Mining Company switched its focus from copper to iron.[6]

In 1846, the company sent an expedition to the site to further explore the area and obtain more ore to test.[5][6] Forging the ore proved a success, and in the winter of 1846–1847, the Jackson Mining Company gathered equipment at the mine.[5] In 1847, the company organized men and machinery and began taking ore out of the mine.[2] It began constructing the Carp River Forge, which was finished the next year.[7] The first pieces of ore from the mine were forged at the Carp River and sold to construct a steamer.[5]

Rise of the Jackson Iron Company (1848–1870s)

In 1848, the Jackson Mining Company was re-incorporated with Fairchild Farrand as president; Berry and Everett and most of the rest of the original investors lost control of the company.[5] In 1849, the company got a new president, Ezra Jones, and a new name: the Jackson Iron Company.[5] In 1850, after numerous problems, the company gave up operation of their forge on the Carp River and leased the forge out.[5] The company was in a precarious financial position, and ceased work for a time on both their forge and mining operations.[5] However, production at the mine soon resumed, although company operations at the forge did not. Jackson began utilising the Marquette forge; however, they did ship some iron ore directly: the first shipment of five tons went to New Castle, Pennsylvania.[5] The purity of this ore shipment attracted attention, and General Joel B. Curtis, president of the Sharon Iron Company of Sharon, Pennsylvania, travelled to Michigan to inspect the mine.[5] Liking what he saw, he purchased a controlling interest in the Jackson Iron Company, and for some years the Jackson location was known as the "Sharon."[5]

With Curtis's guidance, the company began shipping more ore; in 1852, 70 tons were shipped to Sharon Iron.[9] However, shipping ore was still problematic, and in 1857 the Jackson Mine began building a furnace on their property.[9] The slow increase in mining and then furnace construction brought an influx of workers, and a town grew up around the mine and furnace site.[9] In 1857, the town was incorporated as "Negaunee," coming from an Ojibwa phrase meaning "I take the lead," or more loosely, "pioneer."[9]

However, the Jackson Mine was indifferently run, with frequent changes in management, and for some years a "record of disappointments and financial embarrassment."[5] In 1861, the management stabilized, and with the greater demand for iron during the Civil War, the Jackson Iron Company declared its first dividend in 1862.[5] The Jackson Mine ramped up its production, peaking in the late 1860s and early 1870s, with 1871 the year of maximum production.[2][10] The company established an iron furnace at Fayette in 1867,[5] and by 1875 had produced over 1.5 million tons of iron ore.[5]

- Mine Images, c. 1900

Original Jackson Mine pit, photographed c. 1900

Original Jackson Mine pit, photographed c. 1900 Stump where Marji-Gesick showed Philo Everett evidence of iron ore

Stump where Marji-Gesick showed Philo Everett evidence of iron ore

Jackson Mine, photographed 1912

Jackson Mine, photographed 1912 Jackson mine c. 1915. Note miners standing in center right.

Jackson mine c. 1915. Note miners standing in center right.

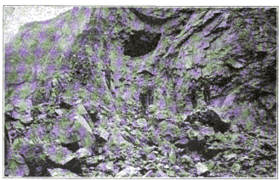

Decline and closure (1870s–present)

After the 1870s, ore prices declined.[2] Even so, by 1900, Jackson Mine had produced over 3.6 million tons of iron ore.[10] However, the Jackson Iron Company was suffering financially, with meager profits due to the declining prices and the irregularity of its deposits.[10] In 1904 the Jackson Mine produced no ore.[12] The mine got a reprieve in 1905, when the Jackson Iron Company was purchased by the Cleveland-Cliffs Company.[13] But, mine yields were still weak, and the Jackson produced no ore in 1908 and 1916.[12] The Jackson Mine closed permanently in 1924, having produced over 4 million tons of ore since its opening in 1856.[2][12]

By the time it closed, the Jackson Mine contained several working pits, as well as trial shafts, a forge, cross-cuts and drifts;[2] some of the underground workings were close to the surface. In the 1950s, the Jackson Mine and portions of the surrounding town of Negaunee were closed due to fears of collapse from undermining.[11] In recognition of the historical significance of the Jackson as the area's first iron mine, the site was designated as a Michigan State Historic Site in 1956 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.[2]

The mine and area around it were acquired by the city of Negaunee in 2003 and the danger from undermining re-evaluated.[11] In 2006, much of "West Old Town Negaunee" and areas around the mine itself were re-opened to the public. The city developed a trail system through the area.[11][14] The overgrown ruins of the early Jackson Mine pit mines can be seen from the trail system.[2][11]

- Mine Images

Drift opening near North Jackson Pit No. 1, 2010

Drift opening near North Jackson Pit No. 1, 2010 Cover over drift near North Jackson Pit No. 1, 2010

Cover over drift near North Jackson Pit No. 1, 2010 Abandoned foundation and machinery, 2010

Abandoned foundation and machinery, 2010

Jackson Park

South of the Jackson Mine site is Jackson Park. This recreational area is 5 acres (2.0 ha) located next to Business M-28 (County Road) southwest of downtown Negaunee. The park has a pair of tennis courts and four horseshoe courts. Before subsidence from mining activities, the park was 11.8 acres (4.8 ha) in size[15] and offered campsites to visitors.

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- "Jackson Mine". Historic Sites Online. Michigan State Housing Development Authority. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- Hannah, Tom A. (1903). Mines and Statistics (Report). Iron Mountain, MI: Michigan Department of Mineral Statistics. pp. 65–69.

- Lake Superior Mining Institute (1898). Proceedings of the Lake Superior Mining Institute. 4. Lake Superior Mining Institute. pp. 90–91.

- Swineford, Alfred P. (1876). History and Review of Copper, Iron, Silver, Slate and Other Material Interests of the South Shore of Lake Superior. Marquette, MI: The Mining Journal. pp. 90–102, 111, 151, 222–223, 233. OCLC 6750767.

- Dunbar, Willis Frederick; May, George S. (1995). Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State (3rd ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 255–257. ISBN 0-8028-7055-4.

- Swank, James Moore (1892). History of the Manufacture of Iron in All Ages: and Particularly in the United States from Colonial Time to 1891 (2nd ed.). New York: Franklin. pp. 320–322. OCLC 7963374.

- Burt, John S. (1986). They Left Their Mark: William Austin Burt and His Sons, Surveyors of the Public Domain. Landmark Enterprises. p. 63. ISBN 0-910845-31-X.

- White, Peter (1886). "The Iron Region of Lake Superior". Michigan Historical Collections. Michigan Historical Commission. 8: 158–159. OCLC 1757295.

- Russell, James (1900). Mines and Statistics (Report). Marquette, MI: Michigan Department of Mineral Statistics. pp. 39–40.

- Storm, Roger; Wedzel, Susan M. (2009). Hiking Michigan (2nd ed.). Human Kinetics. pp. 53–56. ISBN 0-7360-7507-0.

- Lake Superior Iron Ore Association (1952). Lake Superior Iron Ores: Mining Directory and Statistical Record of the Lake Superior Iron Ore District of the United States and Canada (2nd ed.). Lake Superior Iron Ore Association. p. 82. OCLC 1025093.

- "Notes of the Industries". American Manufacturer and Iron World. Pittsburgh: National Iron and Steel Pub. Co. 76 (11): 328. March 16, 1905. OCLC 7824071.

- Basolo, Kristy (January 2007). "History on the Horizon". Marquette Monthly. OCLC 191062221. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- City of Negaunee (n.d.). City of Negaunee Five-Year Recreation Plan (PDF). City of Negaunee. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jackson Mine. |

- Jackson Mine/West old Town trail map from the City of Negaunee