Iron–hydrogen resistor

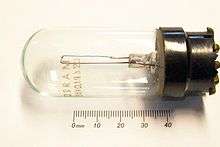

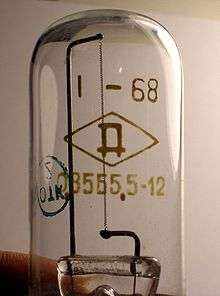

An iron–hydrogen resistor consists of a hydrogen-filled glass bulb (similar to a light bulb), in which an iron wire is located. This resistor has a positive temperature coefficient of resistance. This characteristic made it useful for stabilizing circuits against fluctuations in power-supply voltages.[1] This device is often called a "barretter" because of its similarity to the barretter used for detection of radio signals. The modern successor to the iron–hydrogen resistor is the current source.

Operation

When the current increases, the temperature will increase. The higher temperature leads to a higher electrical resistance, opposing the increase in current. The hydrogen gas protects the iron against oxidation and also enhances the effect, since the solubility of hydrogen in iron increases as temperature increases, resulting in higher resistance.

Uses

Iron–hydrogen resistors were used in the early vacuum tube systems in series with the tube heaters, to stabilize the heater circuit current against fluctuating supply voltage. In 1930s Europe it was popular to combine them in the same glass envelope with an NTC-type thermistor made of UO2 until 1936, known as Urdox resistor and acting as an inrush current limiter for the series heater strings of domestic AC/DC tube radios.

See also

References

External links

- Praktikum der Physik von Wilhelm Walcher Page 241

- Regulator, Type 4A1, Museum of Victoria exhibit No: ST 029230

- Paleoelectronics RDH4 Ch 33, Ch 35