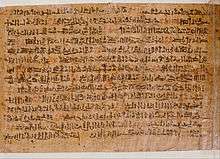

Ipuwer Papyrus

The Ipuwer Papyrus (officially Papyrus Leiden I 344 recto) is an ancient Egyptian hieratic papyrus made during the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, and now held in the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, Netherlands.[1] It contains the Admonitions of Ipuwer, an incomplete literary work whose original composition is dated no earlier than the late Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt (c.1991–1803 BCE).[2]

Content

In the poem, Ipuwer – a name typical of the period 1850–1450 BCE – complains that the world has been turned upside-down: a woman who had not a single box now has furniture, a girl who looked at her face in the water now owns a mirror, while the once-rich man is now in rags. He demands that the Lord of All (a title which can be applied both to the king and to the creator sun-god) should destroy his enemies and remember his religious duties. This is followed by a violent description of disorder: there is no longer any respect for the law and even the king's burial inside the pyramid has been desecrated. The story continues with the description of better days until it abruptly ends due to the missing final part of the papyrus. It is likely that the poem concluded with a reply of the Lord of All, or prophesying the coming of a powerful king who would restore order.[1][3][4]

Discussion

The Ipuwer Papyrus has been dated no earlier than the Nineteenth Dynasty, around 1250 BCE[1][5] but it is now agreed that the text itself is much older, and dated back to the Middle Kingdom, though no earlier than the late Twelfth Dynasty.[2] The Admonitions is considered the world's earliest known treatise on political ethics, suggesting that a good king is one who controls unjust officials, thus carrying out the will of the gods.[6] It is a textual lamentation, close to Sumerian city laments and to Egyptian laments for the dead, using the past (the destruction of Memphis at the end of the Old Kingdom) as a gloomy backdrop to an ideal future.[7]

It was previously thought that the Admonitions of Ipuwer presents an objective portrait of Egypt in the First Intermediate Period.[3][4][8] In more recent times, it was found that the Admonitions, along with the Complaints of Khakheperraseneb, are most likely works of royal propaganda, both inspired by the earlier Prophecy of Neferti: the three compositions have in common the theme of a nation that has been plunged into chaos and disarray and the need for an intransigent king who would defeat chaos and restore maat.[9] Toby Wilkinson suggested that the Admonitions and Khakheperresenb may thus have been composed during the reign of Senusret III, a pharaoh well known for his use of propaganda.[9] In any case, the Admonitions is not a reliable account of early Egyptian history, because of the long time interval between its original composition and the writing of the Leiden Papyrus.[1][5]

Ipuwer and the Book of Exodus

Ipuwer has often been put forward in popular literature as confirmation of the biblical account of the Exodus, most notably because of its statement that "the river is blood" and its frequent references to servants running away. However, these arguments ignore the multitude of ways in which Ipuwer differs from Exodus, such as that it describes the Asiatics as arriving in Egypt rather than leaving, and that the "river is blood" phrase may refer to the red sediment colouring the Nile during disastrous floods, or simply be a poetic image of turmoil.[10] Most histories do not consider information about the Exodus to be recoverable or even relevant to the story of the emergence of Israel.[11]

References

Citations

- Quirke 2014, p. 167.

- Willems 2010, p. 83.

- Gardiner 1961, p. 109-110.

- Grimal 1992, p. 138.

- Shaw 2013, p. 745.

- Gabriel 2002, p. 23.

- Morenz 2003, p. 103–111.

- Bresciani 1969, p. 65.

- Wilkinson 2010, p. 174–175.

- Enmarch 2011, p. 173–175.

- Moore & Kelle 2011, p. 81.

Bibliography

- Bresciani, Edda (1969). Letteratura e poesia dell'antico Egitto. Turin: Einaudi.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Enmarch, Roland (2011). "The Reception of a Middle Egyptian Poem: The Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Lord of All". In Collier, M.; Snape, S. (eds.). Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen (PDF). Rutherford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gabriel, Richard A. (2002). Gods of Our Fathers: The Memory of Egypt in Judaism and Christianity. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 9780313312861.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gardiner, Alan (1961). Egypt of the Pharaohs: an introduction. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 9780195002676.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grabbe, Lester (2014). "Exodus and History". In Dozeman, Thomas; Evans, Craig A.; Lohr, Joel N. (eds.). The Book of Exodus: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation. BRILL. ISBN 9789004282667.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell Books. ISBN 978-0-631-17472-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Megan B.; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Grand Rapids, Michigan; Cambridge, UK. ISBN 9780802862600.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morenz, Ludwig D. (2003). "Literature as a Construction of the Past in the Middle Kingdom". In Tait, John (ed.). 'Never had the liked occurred': Egypt's View of its Past. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781135393625.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quirke, Stephen (2014). Exploring Religion in Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118610527.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaw, Ian (2013). "Pharaonic Egypt". In Mitchell, Peter; Lane, Paul (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191626142.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkinson, Toby A.H. (2010). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781408810026.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willems, Harco (2010). "The First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. 1. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444320060.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- The Admonitions of Ipuwer, an English translation of the Ipuwer Papyrus