Instituto Nacional Mejía

Instituto Nacional Mejía is a public secondary educational institution of Quito. It was founded on June 1, 1897[1] by Eloy Alfaro Delgado,[2] then president of Ecuador.

| Instituto Nacional Mejía | |

|---|---|

| |

| Address | |

Vargas N13-93 y Arenas , | |

| Coordinates | 0°12′44.9814″S 78°30′17.715″W |

| Information | |

| School type | Public, High school |

| Motto | Latin: Per Aspera Ad Astra (Through hardships to the stars) |

| Religious affiliation(s) | Laicism (Secularism) |

| Patron saint(s) | Jose Mejía Lequerica |

| Founded | 1 June 1897 |

| Founder | Eloy Alfaro |

| Rector | Dr. Guillermo del Hierro Pazmiño |

| Principal | Mr Edgar Navarro Noboa |

| Number of students | approximately 8000 |

| Language | Spanish |

| Schedule type | morning and evening |

| Color(s) | Yellow and Blue |

| Sports | Soccer, basketball, athletics, tennis, judo |

| Mascot | Joy |

| Nickname | Patrón Mejía, Coloso de la Vargas |

| Website | Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine |

Mission

According to its authorities, the mission of the institution is as follows:

"It [the Instituto Nacional Mejía] is a secular and experimental High School that educates, prepares and graduates its students with a critical - reflexive mind, and provides them with a scientific Humanist instruction with a view towards social change and national development".

Motto

The school motto is the Latin phrase Per aspera ad astra ("through hardships to the stars").

History

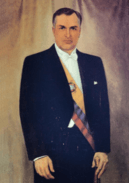

Eloy Alfaro and the foundation of the Instituto Nacional Mejía

.jpg)

The Liberal Revolution of 1895 marked the beginning of a period of numerous reforms and important modernisation efforts in Ecuador.[3] One of the most influential and famous leading figures of the Revolution was Eloy Alfaro, who would subsequently serve as President of Ecuador for two, non-consecutive, terms until his assassination in 1912.[3] Under his direction, the Ecuadorian government started a series of important works such as the completion of the Trans-Andean Railway connecting Quito and Guayaquil.[3] Furthermore, the new Liberal government unfolded a process of secularisation of the state.[3] This is instanciated at the educational level in the construction of several of the first secular educational institutions of the country,[3][4] the clearest example of this being the foundation of the Instituto Nacional Mejía[4] on June 1, 1897 by Alfaro's orders.[5] Other important educational institutions founded by Alfaro include a School of Beaux Arts,[4] the second foundation of the National Conservatory of Music of Ecuador,[6] and the Manuela Cañizares High School.[7]

Previous locations

The Instituto Nacional Mejía was originally located at the north side of the Metropolitan Cultural Centre[5] and was later moved to an old building informally known as the "antiguo Beaterio",[8][5] Spanish for "old nunnery", (which had formerly served for various purposes, from religious retreat to Catholic girls school[2]), at the intersection of the streets José Joaquín de Olmedo and Sebastián de Benalcázar. Both buildings were located at the heart of Quito's Old Town ("Centro Histórico"). In 1922, the high school administration commissioned a new, bigger building, to the German architect Wilhelm Spahr and the local architect Pedro Aulestia Saá,[5] which was to be located at the, back then, northern edge of the city. Thus, the high school would remain at the antiguo Beaterio building only up until the early 1930s.[2] The construction of a new building is also to be taken against the backdrop of the centenary celebrations for the Battle of Pichincha (May 24, 1822), which is conventionally seen as securing the separation of the territories of the then Real Audiencia of Quito from the Spanish Empire, an important antecedent for the construction of Ecuador as a republican nation-state.[9]

Further expansions

The newly founded secondary school quickly acquired popularity and prestige within the country. Hence, following the limited availability of spaces to meet the increasing student demand, a new large building was built in the 1950s on the west side of the block occupied by the Edificio Central.[8] The original purpose of this building was to house the students who came from the various provinces of Ecuador.[8] Later its infrastructure was repurposed to make room for more student classrooms and laboratories.[8] Thus, giving birth to the Edificio Internado. Later, in the 1970s, the School of Telecommunications of the Army of Ecuador ceded its building to the High School, establishing in this way the Edificio Sur.[5] This last building occupies a second block, separated from the rest of the High School by the Antonio Ante street.

Thus, this complex of buildings comprising the Instituto Nacional Mejía is currently located at the north end of Quito's Old Town.

Buildings

Several buildings integrate the current architectural complex of the Instituto Nacional Mejía. These include:

Edificio Central

In 1922, the administration of the Instituto Nacional Mejía orders the construction of this building to the German architect Wilhelm Spahr,[2][5] which would be later amended by the Ecuadorian architect Pedro Aulestia.[2] This will become the future Edificio Central (Spanish for "Central Building"), located at the intersection of the Vargas and Juan Pablo Arenas streets. It was the second public Neoclassical style building of Ecuador,[10] after the Teatro Nacional Sucre and became an icon of the architectural landscape of Quito, in the first half of the 20th century.[5]

The building was constructed on top of irregular terrain.[2][5] Spahr used this irregularity to his advantage by adding some series of long stone staircases leading up to the Neoclassical façade, which added up to the monumentality of the whole structure.[5] In this way, the façade of the school overlooks the entire Juan Pablo Arenas street. Two stone busts rest at the base of the first set of staircases. One depicting Mr. Eloy Alfaro, founder of the institution. The other representing José Mejía Lequerica, patron of the institution.[2]

The Neoclassical style displayed by the Edificio Central is inspired by the architectural style of the 16th century Italian and English rural mansions designed by the Paduan architect Andrea Palladio.[5] Characteristic of this Palladian style is the school's façade composed of tall columns of several floors high and its pediment.[5]

The walls of the Edificio Central are made out of brick and were originally left uncladded until the 1950s when several parts of the building were painted in white, in particular the façade.[2] This lack of cladding would have been the result of a lack of funding.[2] The building possesses a tiled roof and timber floors.[2]

Spahr originally envisioned the central part of the building (marked by the façade) as serving for administrative purposes, whereas the pavilions on both extremes were conceived as student accommodations, and the sections in between as spaces for laboratories and classrooms.[5] But by 1928 this idea was abandoned and the pavilions at both ends of the Edificio Central were repurposed to fit more classrooms and laboratories.[5]

Edificio Internado

Edificio Sur

It was built in 1955, neighbouring the Edificio Central of the Instituto Nacional Mejía, it originally lodged the Ecuadorian Army School of Telecommunications, and from 1968 it also housed the Ecuadorian Army Corps of Engineers.[11] The building was ceded to the Instituto Nacional Mejía in the 1970s, due to the latter's struggle to cope with its high demand of students.[11] The building is nowadays part of a larger complex that occupies its entire block, separated from the rest of the educational centre by the Antonio Ante street. The original building presents Mudejar and Art Deco architectural elements.[11]

Stadium

Library

The library of the Instituto Nacional Mejía holds about 45 000 books[12] and is open to the public. The oldest of its books dates back to 1656 and was written by the Augustinian friar Gaspar de Villaroel.[12] The collection also includes Reflexiones Acerca de las Viruelas (1785), "Reflexions on Smallpox", a medical manuscript by the prominent 18th century physician, writer, and lawyer Eugenio Espejo, who would become "the first scholar to address issues of prophylaxis and hygiene in the Real Audiencia of Quito".[13]

Following the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from Ecuador, its members abandoned the country leaving behind their entire library collections, which were then stored in several sacks.[12] Then, during the presidency of Eloy Alfaro, founder of the high school, the Jesuits' book collections were distributed among the National Library, the Library of the Central University of Ecuador (UCE), and the Library of the Instituto Nacional Mejía.[12] This accounts for the latter's ownership of books that significantly predate the founding itself of the high school.

Museums

The Instituto Nacional Mejía possesses two museums within its architectural complex: a natural history museum and an ethnographic museum. Both are open to the public.

Natural History Museum

Known as Museo de Ciencias Naturales ("Museum of Natural Science"), it is regarded as one of the first and most important of its kind in the country.[10] It contains a collection of 2 847 animals comprising 2 246 birds, 293 mammals, 172 reptiles, 122 fish, and 14 amphibians.[14]

It was founded in 1905[15] by disposition of Mr. Eloy Alfaro, who ordered the purchase of 50 animal specimens from the Deyrolle house in Paris along with some national specimens.[10][15] In 1920 there was an acquisition of an additional 1 000 specimens of Ecuadorian fauna.[10] The collection was later transferred to the Edificio Central (Central Building) once its construction was completed, where it remains today. As the years progressed, the collection would continue to grow intermittently with the addition of private collections from leading families of the country.[10]

In 1936, Gustavo Orcés, regarded as the father of Zoology studies in Ecuador,[16] insisted on identifying and classifying the ornithologic section held at the museum.[17] During this work, the pioneer Ecuadorian zoologist managed to identify specimens pertaining to around 1 000 species of the 1 400 known in the country at the time.[17] In 1943, he finished his taxonomic labour at the museum.[17][10]

In 1981, an agreement with the Central Bank of Ecuador ensured the funding for the restoration and rehabilitation of the museum.[10] This intervention was scientific and museographic in character and it included once again the participation of Gustavo Orcés, along with other teachers of the high school such as Fernando Ortiz, Osvaldo Báez, and Bolívar Reinoso.[10]

As already established, the collection of birds is the most important and numerous of the museum. It includes birds as diverse as "curiquingues", "tayos", condors, and various species of tucans, owls, gavilans and parrots. In addition, there are embalmed species of Galápagos tortoise, sharks, iguanas, snakes, and mammals like the jaguar, armadillos, bats, rodents and marsupials.[10]

Ethnographic Museum

The Ethnographic Museum contains a collection of 57 wooden sculptures with traditional clothing and settings depicting several of the ethnic groups of the country,[18] covering the three natural regions of the Ecuadorian mainland and divided into 18 rooms.[19] It also serves as the de facto Anthropological Museum of Ecuador.[20]

In 1950, the pieces of the Anthropological Museum of Ecuador were owned by the National Institute of Anthropology and Geography,[18] and were exhibited until 1952.[20] In 1974 those pieces (22 wooden sculptures) were donated to the Instituto Nacional Mejía,[20][18] thus establishing its Ethnographic Museum. The author of the pieces was the sculptor Galo Tobar.[19]

A total of 21 ethnicities are depicted in the 18 rooms.[20] The aim of the museum is to represent some of the multiple ethnic groups of Ecuador in their daily (traditional) activities. The groups represented include Shuar, Achuar, Cofán, Huaorani, Salasaca, Tsachila, Awá, Saraguro and Otavalo people among others. It also includes sculptures of Danzantes of Cayambe (also known as Danzantes of Aricucho), and Danzantes of Huachi.[20]

In addition, this museum possesses some original indigenous items such as head rings, and "tzantzas". It also displays some embalmed specimens of local animals, dioramas, and fragments of Ecuadorian megafauna bones.

Notable Alumni

The school is associated, through its alumni, with several relevant figures within the Ecuadorian context and beyond, in particular in the cultural sphere. Some of its alumni include:

Rosa Cabeza de Vaca, graduated in 1903. Notorious for being the first female student to have graduated from the Instituto Nacional Mejía, and therefore creating an important precedent in the country.[21][22]

Hugo Alemán (Quito, June 10, 1898 – Quito, December 3, 1983), poet[23]. He worked in the Pichincha provincial government as secretary, was the director of the Library of the Central University of Ecuador and the Library of the Instituto Nacional Mejía[24]. He integrated the "La Ronda" group along with Ricardo Álvarez and Augusto Arias.[25]

Augusto Arias[26][27] (Quito, March 15, 1903 – Quito, August 23, 1974), poet.

Jorge Carrera Andrade (Quito, September 18, 1903 – Quito, November 7, 1978), poet and diplomat. He was also teacher of literature at the Instituto Nacional Mejía before accepting a position as Ecuadorian diplomat to France.[28]

Gonzalo Escudero Moscoso (Quito, September 28, 1903 – Brussels, December 10, 1971), poet and diplomat. He was also teacher of aesthetics and logic both at the Instituto Nacional Mejía and at the Central University of Ecuador.[29]

Jorge Icaza (Quito, June 10, 1906 – Quito, May 26, 1978), novelist. Achieved international notoriety for his novel "Huasipungo" (1934).[30]

Nelson Estupiñán Bass[31][32] (Súa, September 19, 1912 – Hershey,[33] March 1?,[33][34][35] 2002), novelist, poet, playwright and activist. He was awarded the Eugenio Espejo Prize in 1993.[32]

Ricardo Descalzi (Riobamba, September 22, 1912 – Quito, November 29, 1990), physician, playwright, theatrical critic, and novelist.[36][37] Co-founder of the literary magazine "Surcos" with Alfredo Llerena and Arturo Meneses.[38][39] Member of the Ecuadorian National Academy of History.[39]

José Alfredo Llerena (Guayaquil, July 1912 – Guayaquil, 1977), poet and journalist.[40] Co-founder of the literary magazine "Surcos".[39]

Alejandro Carrión (Loja, March 11, 1915 – Quito, January 4, 1992), poet, novelist and journalist. He was the recipient of the Eugenio Espejo Prize in 1986[41] and a Maria Moors Cabot Prize in 1961.[42]

Jorge Enrique Adoum[43] (Ambato, June 29, 1926 – Quito, July 3, 2009), essayist, poet, novelist, and diplomat. Awarded with the Premio Nacional de Poesía (1952)[44], Casa de las Américas Prize (1960)[45][46], Xavier Villaurrutia Award (1976)[47] and Eugenio Espejo Prize (1989)[48]. Personal secretary of Pablo Neruda (1946 – 1948)[44][49]. National Director of Culture (1961-1963)[44]. He worked at the United Nations and UNESCO[50]. He occupied for a time a position as teacher of literature at his former high school[44].

Oswaldo Muñoz Mariño[51] (Riobamba, December 24, 1923 – February 20, 2016) architect and painter. Awardee of the Eugenio Espejo Prize in 1999.[52] He was also professor of architecture at the UNAM.[52][53]

Raúl Pérez Torres (Quito, May 11, 1941), writer.[36][54] Former president of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (CCE) for two terms (2000 – 2004 and 2012 – 2016).[55] Minister of Heritage and Culture since 2017.[56]

In addition to poets, novelists and essayists, several sportmen, army personnel and politicians, included two presidents of Ecuador, have studied at this institution:

Isabel Robalino Bolle (Barcelona, October 14, 1917 – ), historian, lawyer and politician. She pioneered women's participation in several areas of Ecuadorian public life.[57] First female lawyer of Ecuador[57] in 1944.[58] First female member of Quito's City Council in the 1940s.[57] First female senator of Ecuador in 1968.[59] In addition, she has played a key role in the development of trade unions in the country. She is currently member of the Ecuadorian National Academy of History.[59]

Carlos Andrade Marín (Quito, June 15, 1904 – unknown, Mach, 5, 1968), physician and politician. He later worked as professor of zoology at this institution, of which he also became its principal.[60] Founder of the Association of Alumni of the Instituto National Mejía. Member and head of Quito's City Council in 1935.[60] Minister of Education.

Frank Vargas Pazzos (Chone, July 15, 1934), commander-in-chief of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces (1983 – 1986), congressman and Minister of Government (1996 – 1997).[61] He ran for the presidential elections on several occasions.

Paco Moncayo (Quito, October 8, 1940), commander-in-chief of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces (1996-1998), Mayor of Quito (2000 – 2009), and former congressman.[61][36]

Milton Luna Tamayo (Quito, May 18, 1958 – ). Historian. Minister of Education [62] (2018 – 2019).[63]

Galo Plaza Lasso[64] (New York City, February 17, 1906 – Quito, January 28, 1987), Mayor of Quito (1938 – 1939), president of Ecuador (1948 – 1952). Secretary General of the Organization of American States (1968 – 1975).[65] Co-founder of the Colegio Americano de Quito.

Lenín Moreno Garcés (Nuevo Rocafuerte, March 19, 1953 – ), current president of Ecuador, spent part of his secondary education at this institution.[61]

References

- Biography of Eloy Alfaro

- Vv.Aa. (2004). Quito: An Architectural Guide. 2. Quito - Seville. ISBN 978-84-8095-363-4.

- Ayala Mora, Enrique (2005). Resumen de historia del Ecuador. Quito: Corporación Editora Nacional. pp. 87–90. ISBN 978-9978-84-179-2.

- Carrión, Benjamin (2008). El cuento de la Patria. Breve Historia del Ecuador. Quito: Libresa. pp. 233–235. ISBN 978-9978-49-256-7.

- López Molina, Héctor (2018). "Los ladrillos de Quito: Colegio Nacional Mejía". Los ladrillos de Quito.

- "Historia". Conservatorio Nacional de Música (in Spanish). 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- "Historia". Unidad Educativa Lizardo Garcia (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Telégrafo, El (2014-10-19). "Un ligero vistazo a la rica y compleja historia del Patrón Mejía". El Telégrafo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Ayala Mora, Enrique (2005). Resumen de historia del Ecuador. Quito: Corporación Editora Nacional. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-9978-84-179-2.

- MvProduccionesEC (2013-10-02), MUSEO CIENCIAS NATURALES - INSTITUTO NACIONAL MEJÍA, retrieved 2019-03-09

- López Molina, Héctor. "Antigua Escuela de Telecomunicaciones del Ejército". Los ladrillos de Quito. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Hora, Diario La. "Manuscrito sobre la viruela de Espejo está en el Mejía - La Hora". La Hora Noticias de Ecuador, sus provincias y el mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Ramírez Martín, Susana María (2003). La Real Expedición Filantrópica de la Vacuna en la Real Audiencia de Quito. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. p. 92. ISBN 978-84-669-1092-7.

- Pérez, Valeria (2015-05-07). "MUSEOS DE QUITO : Museo Etnografico y de Ciencias Naturales del Colegio Nacional Mejía". MUSEOS DE QUITO. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- CIESPAL (2009-10-06), Museo del Colegio Mejía, retrieved 2019-03-09

- "Ecuador Terra Incognita - gustavo orces". www.terraecuador.net. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Semblanza de Gutavo Orcés Villagómez, el primer zoólogo ecuatoriano". Periódico Opción (in Spanish). 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Meza, Jennifer (2015-05-06). "MUSEO ETNOGRÁFICO DEL COLEGIO NACIONAL MEJÍA". MUSEOS DE QUITO (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Museo". www.ilam.org. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- MvProduccionesEC (2013-10-02), MUSEO ETNICO - INSTITUTO NACIONAL MEJÍA, retrieved 2019-03-10

- RevistaVive, Pasante (2017-03-08). "Mujeres que marcaron la historia del Ecuador". Revista Vive (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- "10 mujeres ecuatorianas que marcaron la historia del país". El Comercio. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- Pérez Pimentel, Rodolfo. "Hugo Mayo". Diccionario Biográfico Ecuador.

- Alemán, Hugo (2009). Poesía y prosa. Quito: La Palabra. pp. 179–189. ISBN 978-9942-02-357-5.

- "Aleman Hugo - Personajes Históricos". Enciclopedia Del Ecuador (in Spanish). 2015-10-13. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Arias, Augusto (2004). Poesía. Quito: Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (CCE). p. 7. ISBN 978-9978-62-348-0.

- "Arias Augusto - Personajes Históricos". Enciclopedia Del Ecuador (in Spanish). 2015-10-13. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Carrera Andrade, Jorge (2005). Antología Poética. Quito: Libresa. p. 10. ISBN 978-9978-80-900-6.

- Escudero, Gonzalo (2004). Poesía. Quito: Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (CCE). p. 7. ISBN 978-9978-62-349-7.

- Icaza, Jorge (1994). Huasipungo. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra. ISBN 978-84-376-1251-5.

- TheBiography.us; TheBiography.us. "Biography of Nelson Estupiñán Bass (1912-2002)". thebiography.us. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Choin, David (2016). "UTPL: Nelson Estupiñán Bass".

- Richards, Henry J. (Spring 2003). "Remembering Nelson Estupiñán Bass (1912-2002)". Afro-Hispanic Review. 22 (1): 75–77. JSTOR 23054471.

- Hora, Diario La. "Nelson Estupiñán Bass inició el último viaje - La Hora". La Hora Noticias de Ecuador, sus provincias y el mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Nelson Estupiñán Bass, los cien años del escritor de la negritud". El Universo (in Spanish). 2012-09-22. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Hora, Diario La. "El Mejía: un Colegio tradicional - La Hora". La Hora Noticias de Ecuador, sus provincias y el mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Cortés, Eladio; Cortes, Eladio; Barrea-Marlys, Mirta (2003). Encyclopedia of Latin American Theater (in Spanish). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313290411.

- "Evocación al escritor Ricardo Descalzi". El Universo (in Spanish). 2012-09-21. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Descalzi Dr. Ricardon - Personajes Históricos". Enciclopedia Del Ecuador (in Spanish). 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Coll, Edna (1974). Indice informativo de la novela hispanoamericana (in Spanish). La Editorial, UPR. ISBN 9780847720125.

- "Alejandro Carrión Aguirre (1915 - 1992) | Municipio de Loja". www.loja.gob.ec. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Past Cabot Winners List" (PDF). 2016.

- Díaz-Granados, José Luis (2005). "Jorge Enrique Adoum". www.latinoamerica-online.info. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Adoum, Jorgenrique (2008). Poesía hasta hoy (1949-2008). Volumen I. Quito: Ediciones Archipiélago. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-9978-376-00-3.

- Adoum, Jorge Enrique. Entre Marx y una mujer desnuda. Editorial El Conejo.

- "Jorge Enrique Adoum". El Tiempo. 6 July 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Premio Xavier Villaurrutia de Escritores para Escritores". 2010-06-26. Archived from the original on 2010-06-26. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- Adoum, Jorge Enrique (2007). Poesía viva del Ecuador. Antología. Quito: Libresa. p. 21. ISBN 978-9978-80-488-9.

- "Anecdotario del escritor ecuatoriano Jorge Enrique Adoum con Pablo Neruda, de quien fue secretario particular - Proceso" (in Spanish). 1996-11-02. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- "Fallece el escritor ecuatoriano Jorge Enrique Adoum, secretario del poeta Pablo Neruda". La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- "OSWALDO MUÑOZ". www.culturaenecuador.org. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "El maestro Oswaldo Muñoz Mariño falleció a sus 92 años". El Comercio. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Telégrafo, El (2017-03-04). "Oswaldo Muñoz Mariño enlazó la mano con el ojo, eludiendo el cerebro". El Telégrafo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Poemas para tocarte". www.casadelacultura.gob.ec (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Historia de Presidentes Casa de la cultura". www.casadelacultura.gob.ec (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "¿Quiénes son los integrantes del Gabinete de Lenín Moreno? | El Comercio". 2017-05-24. Archived from the original on 2017-05-24. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "A los 99 años, Isabel Robalino sigue en la lucha | Plan V". 2017-04-19. Archived from the original on 2017-04-19. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Isabel Robalino, la madre de los obreros : Noticias de Quito : La Hora Noticias de Ecuador, sus provincias y el mundo". 2017-04-18. Archived from the original on 2017-04-18. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "El siglo ganado de Isabel Robalino". El Comercio. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Dr Carlos Andrade Marin - Ensayos y Trabajos - Alejandro93". www.clubensayos.com. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Lenín Moreno y otros personajes resaltan la rebeldía del Mejía, retrieved 2019-04-25

- La Posta (2019-05-17), Castigo Divino: Milton Luna, retrieved 2019-05-23

- "Milton Luna deja el Ministerio de Educación". Vistazo (in Spanish). 2019-06-25. Retrieved 2019-08-05.

- "Presidentes del Ecuador, Galo Plaza Lasso, Camilo Ponce Enriquez". www.trenandino.com. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Galo Plaza, hace 50 años fue Secretario General de la OEA – Periodico Expectativa – Noticias de Ibarra Imbabura Ecuador" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-29.