Initial and final state radiation

In particle physics, initial and final state radiation refers to certain kinds of radiative emissions that are not due to particle annihilation.[1][2] It is important in experimental and theoretical studies of interactions at particle colliders.

Explanation of initial and final states

Particle accelerators and colliders produce collisions (interactions) of particles (like the electron or the proton). In the terminology of the quantum state, the colliding particles form the Initial State. In the collision, particles can be annihilated or/and exchanged, producing possibly different sets of particles, the Final States. The Initial and Final States of the interaction relate through the so-called scattering matrix (S-matrix).

The probability amplitude for a transition of a quantum system from the initial state having state vector to the final state vector is given by the scattering matrix element

where is the S-matrix.

Electron-positron annihilation example

The electron-positron annihilation interaction:

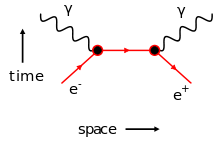

has a contribution from the second order Feynman diagram shown adjacent:

In the initial state (at the bottom; early time) there is one electron (e−) and one positron (e+) and in the final state (at the top; late time) there are two photons (γ).

Other states are possible. For example, at LEP,

e+

+

e−

→

e+

+

e−

, or

e+

+

e−

→

μ+

+

μ−

are processes where the initial state is an electron and a positron colliding to produce an electron and a positron or two muons of opposite charge: the final states.

Phenomenology

In the case of initial-state radiation, one of the incoming particles emit radiation (such as a photon, wlog) before the interaction with the others, so reduces the beam energy prior to the momentum transfer; while for final-state radiation, the scattered particles emit radiation, and since the momentum transfer has already occurred, the resulting beam energy decreases.

In analogy with bremsstrahlung, if the radiation is electromagnetic it is sometimes called beam-strahlung, and similarly can have gluon-strahlung (as shown in the Feynman figure with the gluon) as well in the case of QCD.

Computational issues

In these simple cases, no automatic calculation software packages are needed and the cross-section analytical expression can be easily derived at least for the lowest approximation: the Born approximation also called the leading order or the tree level (as Feynman diagrams have only trunk and branches, no loops). Interactions at higher energies open a large spectrum of possible final states and consequently increase the number of processes to compute, however.

The calculation of probability amplitudes in theoretical particle physics requires the use of rather large and complicated integrals over a large number of variables. These integrals do, however, have a regular structure, and may be represented graphically as Feynman diagrams. A Feynman diagram is a contribution of a particular class of particle paths, which join and split as described by the diagram. More precisely, and technically, a Feynman diagram is a graphical representation of a perturbative contribution to the transition amplitude or correlation function of a quantum mechanical or statistical field theory. Within the canonical formulation of quantum field theory, a Feynman diagram represents a term in the Wick's expansion of the perturbative S-matrix. Alternatively, the path integral formulation of quantum field theory represents the transition amplitude as a weighted sum of all possible histories of the system from the initial to the final state, in terms of either particles or fields. The transition amplitude is then given as the matrix element of the S-matrix between the initial and the final states of the quantum system.

References

- Radiative Corrections, Peter Schnatz. Accessed 08 March 2013.

- Reducing the Uncertainty in the Detection Efficiency for Π0 Particles at BABAR, Kim Alwyn. Accessed 08 March 2013.

External links

- Initial and final state radiation in Z production, A Quantum Diaries Survivor.

- Beam-Beam Interaction, D. Schulte

- ISR and Beamstrahlung