Indian vernacular architecture

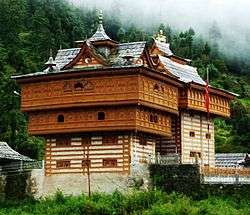

Indian vernacular architecture the informal, functional architecture of structures, often in rural areas of India, built of local materials and designed to meet the needs of the local people. The builders of these structures are unschooled in formal architectural design and their work reflects the rich diversity of India's climate, locally available building materials, and the intricate variations in local social customs and craftsmanship. It has been estimated that worldwide close to 90% of all building is vernacular, meaning that it is for daily use for ordinary, local people and built by local craftsmen.[1]

.jpg)

The term vernacular architecture in general refers to the informal building of structures through traditional building methods by local builders without using the services of a professional architect. It is the most widespread form of building.[2]

In India there are numerous traditional regional styles, although there is much in common in the styles of the Hindi belt in the north. Compared to Hindu temple architecture and Indo-Saracenic architecture there was traditionally much more use of wood rather than stone, though today brick and concrete are more typical, and Indian versions of Western styles dominate in recent buildings.

Categories

Indian vernacular architecture has evolved organically over time through the skillful craftsmanship of the local people. Despite the diversity, this architecture can be broadly divided into three categories.

Kachcha

A kachcha is a building made of natural materials such as mud plaster, bamboo, thatch and wood and is therefore a short-lived structure. Since it is not made for endurance it requires constant maintenance and replacement. The practical limitations of the building materials available dictate the specific form which can have a simple beauty. The advantage of a kachcha is that construction materials are cheap and easily available and relatively little labor is required.

Pakka

A pakka is a structure made from materials resistant to wear, such as forms of stone or brick, clay tiles, metal or other durable materials, sometimes using mortar to bind, that does not need to be constantly maintained or replaced. However, such structures are expensive to construct as the materials are costly and more labor is required. A pakka (or sometimes pukka) may be elaborately decorated in contrast to a kachcha.

Semi-Pukka

A combination of the kachcha and pukka style, the semi-pukka, has evolved as villagers have acquired the resources to add elements constructed of the durable materials characteristic of a pukka. Architecture as always evolves organically as the needs and resources of people change. Majority of traditional vernacular architecture falls under semi-pukka.

Regional variation

Building material depends on location. In hilly country where rocky rubble, ashlar, and pieces of stone are available, these can be patched together with a mud mortar to form walls. Finer stonework veneer covers the outside. Sometimes wood beams and rafters are used with slate tiles for roofing if available. Houses on hills usually have two stories, with the livestock living on the ground floor. Often a verandah runs along the side of the house. The roof is pitched to deal with the monsoon season and the house may sit on raised platform, plinths or bamboo poles to cope with floods.

On the flat lands, adobes are usually made of mud or sun-baked bricks, then plastered inside and out, sometimes with mud mixed with hay or even cow dung and whitewashed with lime.

Where bamboo is available it is widely used for all parts of the home as it is flexible and resilient. Also widely used is thatch from plants such as elephant grass, paddy, and coconut. In the south, clay tiles are used for pukka roofing while various plant material such as coconut palm is common for the Kamchatka.

Gallery

Traditional decoration on wooden windows.

Traditional decoration on wooden windows. Outside of wooden pole house, Gujarat

Outside of wooden pole house, Gujarat Wooden carving outside Pole house, brick and wood joinery walls with lime plaster, Gujarat

Wooden carving outside Pole house, brick and wood joinery walls with lime plaster, Gujarat Rows of sandstone haveli in Rajasthan.

Rows of sandstone haveli in Rajasthan. Wooden Wada house courtyard, Mahatrastra.

Wooden Wada house courtyard, Mahatrastra.- Traditional house in southern India with courtyard.

Kitchen in southern India house, lime plaster and stone floor.

Kitchen in southern India house, lime plaster and stone floor. Merchent Chettinad mansion in Tamil Nadu

Merchent Chettinad mansion in Tamil Nadu Row of wooden pillars and carving in Chettinad house, Tamil Nadu

Row of wooden pillars and carving in Chettinad house, Tamil Nadu Ornamentation on wooden door, Gujarat.

Ornamentation on wooden door, Gujarat. Ornate jharokha windows.

Ornate jharokha windows. Ornate jharoka with 'Do-chala' slooping roof

Ornate jharoka with 'Do-chala' slooping roof Construction of bamboo wall in Northeast India.

Construction of bamboo wall in Northeast India. Reconstruction of a Naga hut, Nagaland.

Reconstruction of a Naga hut, Nagaland.

See also

Notes

- "Vernacular Architecture". Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- "What is Vernacular Architecture". Retrieved 2007-03-31.

References

- Thapar, Bindia (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

- What is Vernacular Architecture? (Long definition)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vernacular architecture of India. |