Indian famine of 1896–97

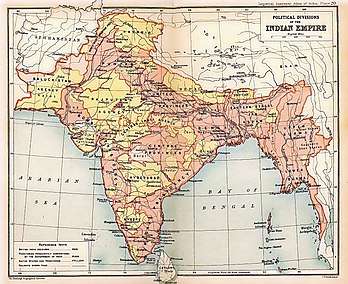

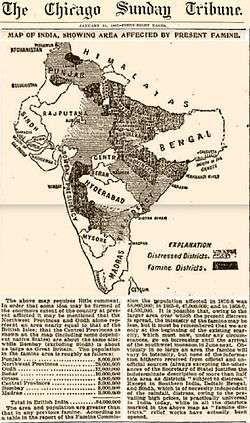

The Indian famine of 1896–1897 was a famine that began in Bundelkhand, India, early in 1896 and spread to many parts of the country, including the United Provinces, the Central Provinces and Berar, Bihar, parts of the Bombay and Madras presidencies, and parts of the Punjab; in addition, the princely states of Rajputana, Central India Agency, and Hyderabad were affected.[1][2] All in all, during the two years, the famine affected an area of 307,000 square miles (800,000 km2) and a population of 69.5 million.[1] Although relief was offered throughout the famine-stricken regions in accordance with the Provisional Famine Code of 1883, the mortality, both from starvation and accompanying epidemics, was very high: approximately one million people are thought to have died.[1]

| Indian famine of 1896–97 | |

|---|---|

| Country | India, the princely states of Rajputana, Central India Agency, and Hyderabad |

| Period | 1896–97 |

| Total deaths | ca. 1 million |

| Observations | drought |

Course

The Bundelkhand district of Agra Province experienced drought in the autumn of 1895 as a result of poor summer monsoon rains.[1] When the winter monsoon failed as well, the provincial government declared a famine early in 1896 and began to organise relief.[1] However, the summer monsoon of 1896 brought only scanty rains, and soon the famine had spread to the United Provinces, Central Provinces and Berar, portions of the presidencies of Bombay and Madras, and of the provinces of Bengal, Punjab, and even Upper Burma.[1] The native states affected were Rajputana, Central India Agency, and Hyderabad.[1] The famine affected mostly British India: of the total area of 307,000 square miles (800,000 km2) affected, 225,000 square miles (580,000 km2) lay in British territory; similarly, of the total famine-afflicted population of 67.5 million, 62.5 million lived in British territory.[1]

The summer monsoon rains of 1897, however, were abundant, as was the following harvest which ended the famine in Autumn 1897.[3] However, the rains, which were particularly heavy in some regions set off a malaria epidemic which killed many people; soon thereafter, an epidemic of the bubonic plague began in the Bombay Presidency, which although not very lethal during the famine year, would, in the next decade, become more virulent and spread to the rest of India.[3]

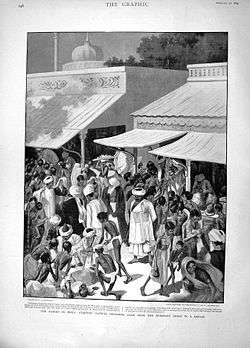

Famine relief

A decade earlier, in 1883, the Provisional Famine Code had been promulgated soon after the report of the first Indian Famine Commission was submitted in 1880.[1] Now, guided by the Code, relief was organised for 821 million units[4] at a cost of Rs. 72.5 million (then approx. £4,833,500).[1] Revenue (tax) was remitted to the tune of Rs. 12.5 million (£833,350) and credit totalling Rs. 17.5 million (£1,166,500) was given.[1] A charitable relief fund collected a total of Rs. 17.5 million (£1,166,500) of which Rs. 1.25 were collected in Great Britain.[1]

Even so, the mortality resulting from the famine was great; it is thought that in the British territory alone, between 750,000 and 1 million people died of starvation.[3] Although the famine relief was reasonably effective in the United Provinces, it failed in the Central Provinces, especially among tribal groups, who were reluctant to perform labour in public works to earn food rations, and who, according to Famine Code guidelines, did not qualify for "charitable relief."[3]

Weavers in the Bombay Presidency

The Famine Commission of 1880 had made special provisions for the relief of weavers, who practised the only trade other than agriculture that employed rural Indians.[5] The Commission had recommended that weavers be given relief by offering them monetary advances for weaving coarse cloth or wool that could then be used in poor-houses or hospitals.[5] This was preferable, it was felt, to having them produce the finer cloth of their trade, such as silk, for which there was no demand during a famine.[5]

However, by 1896, the rural weavers in the Bombay Presidency, who were now having to compete with the increasing number of local cotton mills, were already in dire economic straits.[6] Consequently, when the famine began, not only were they the first to apply for relief, but also did so in numbers that were much larger than had been anticipated.[6] Since the government could now offer only limited relief to them in their own trade because of the large capital required, the majority of weavers—either of their own accord or as a result of official dictate—sought the conventional "relief works," which included earth-works and the breaking of rock and metal for building roads.[6]

Tribal groups in Chota Nagpur

In Chota Nagpur, East India, awareness of the famine came late in 1896 when it was discovered that the rice crop in the highlands of Manbhum district had failed entirely on account of very little rain the previous summer.[7] The rice, grown on small terraces cut into the hillsides and forming staggered step-like patterns, was completely dependent on the monsoon: the only means of irrigation being water from the summer rains which flooded these terraces and which was then allowed to stand until mid-autumn when the crop ripened.[7] The region also had a large proportion of tribal groups including Santals and Mundas who had traditionally relied on forest produce for some of their food intake.[7]

As the local government began to plan relief measures for the famine, they included, in the list of food resources available, forest produce for the tribal groups; the planned government-sponsored relief for these groups was accordingly reduced.[7] The previous decades, however, had seen large-scale deforestation in the area, and what forest that remained was either in private hands or in reserves.[8] The tribal groups, whose accessible forests were now few and far between, consequently, first endured malnutrition and later, in their weakened state, fell prey to a cholera epidemic which killed 21 people per thousand.[8]

Food exports in Madras Presidency

Although the famine in the Madras Presidency was preceded by a natural calamity in the form of a drought, it was made more acute by the government's policy of laissez faire in the trade of grain.[9] For example, two of the worst famine-afflicted areas in the Madras Presidency, the districts of Ganjam and Vizagapatam, continued to export grains throughout the famine.[9] The table below shows exports and imports for the two districts during a five-year period beginning in 1892.[9]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cattle in the Deccan

Farming in the dry Deccan region of the Bombay Presidency required more farm animals—typically bullocks to pull the heavier ploughs—than were needed in other, wetter, regions of India; often, up to six bullocks were needed for ploughing.[10] For most of the first half of the 19th century, farmers in the Deccan did not own enough bullocks to farm effectively.[10] Consequently, many plots were ploughed only once every three or four years.[10]

In the second half of the 19th century, cattle numbers per farmer did increase; however, the cattle remained vulnerable to famines.[10] When the crops failed, people were driven to change their diets and eat seeds and fodder.[11] Consequently, many farm animals, especially bullocks, slowly starved.[10] The famine of 1896–97 proved particularly devastating for bullocks; in some areas of the Bombay Presidency, their numbers had not recovered some 30 years later.[10]

Epidemics

Epidemics of many diseases, especially cholera and malaria, usually accompanied famines.[12] In 1897, an epidemic of the bubonic plague broke out as well in the Bombay Presidency and, in the next decade, would spread to many parts of the country.[13] However, other diseases took a bigger toll during the famine of 1896–97.[13]

Typically, deaths from cholera and dysentery and diarrhoea peaked before the rains as large groups of people collected on a daily basis to receive famine relief.[12] Malaria epidemics, on the other hand, usually began after the first rains when the famine-afflicted population left the relief-camps for their villages; there, new pools of standing water attracted the mosquito-borne virus to which their already enfeebled condition offered little resistance.[12] The following table compares the number of deaths due to different diseases occurring in the famine year with the average number occurring in the five years preceding the famine in the Central Provinces and Berar and the Bombay Presidency.[13] In each case, the mortality had increased during the famine year; this included the small number of officially registered suicides included in the "injuries" category below.[13]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mortality

Estimates of the total famine related deaths during this period vary. The following table gives the varying estimates of total famine related deaths between 1896 and 1902 (including both the 1899–1900 famine and the famine of 1896–1897).[14]

| Estimate (in millions) | Done by | Publication |

|---|---|---|

| 8.4 | Arup Maharatna Ronald E. Seavoy |

The Demography of Famines: An Indian Historical Perspective, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996 Famine in Peasant Societies (Contributions in Economics and Economic History), New York: Greenwood Press, 1986 |

| 6.1 | Cambridge Economic History of India | The Cambridge Economic History of India, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, 1983 |

Aftermath

Both the famine and the relief efforts were painstakingly analysed by the Famine Commission of 1898 presided by Sir James Broadwood Lyall, the former Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab. The Commission affirmed the broad principles of famine relief enunciated by the first Famine Commission of 1880, but made a number of changes in implementation. They recommended increasing the minimum wage in the "relief works," and extending gratuitous (or charitable) relief during the rainy season. They also defined new rules for relief of "aboriginal and hill tribes" who had been found difficult to reach in 1896–97; in addition, they stressed generous remissions of land revenue. The recommendations were soon to be tested in the Indian famine of 1899–1900.[3]

See also

- Indian famine of 1899–1900

- Famines, Epidemics, and Public Health in the British Raj

- Timeline of major famines in India during British rule (1765 to 1947)

- Company rule in India

- Famine in India

- Drought in India

Notes

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 490

- C.A.H. Townsend, Final repor of thirds revised revenue settlement of Hisar district from 1905-1910, Gazetteer of Department of Revenue and Disaster Management, Haryana, point 22, page 11.

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 491

- 1 unit = relief for one individual for one day

- Muller 1897, pp. 285–286

- Muller 1897, pp. 287–288

- Damodaran 2007, p. 169

- Damodaran 2007, p. 170

- Ghose 1982, p. 380

- Tomlinson 1993, pp. 82–83

- Roy 2006, p. 363

- Dyson 1991a, p. 15

- Dyson 1991a, p. 16

- Davis 2001, p. 7

References

- Damodaran, Vinita (2007), "Famine in Bengal: A Comparison of the 1770 Famine in Bengal and the 1897 Famine in Chotanagpur", The Medieval History Journal, 10 (1&2): 143–181, doi:10.1177/097194580701000206

- Davis, Mike (2001), Late Victorian Holocausts, Verso Books. Pp. 400, ISBN 978-1-85984-739-8

- Dyson, Tim (1991a), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part I", Population Studies, 45 (1): 5–25, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145056, JSTOR 2174991

- Ghose, Ajit Kumar (1982), "Food Supply and Starvation: A Study of Famines with Reference to the Indian Subcontinent", Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 34 (2): 368–389, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041557, PMID 11620403

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic (Chapter X: Famine, pp. 475–502), Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552.

- Muller, W. (1897), "Notes on the Distress Amongst the Hand-Weavers in the Bombay Presidency During the Famine of 1896–97", The Economic Journal, 7 (26): 285–288, doi:10.2307/2957261, JSTOR 2957261

- Roy, Tirthankar (2006), The Economic History of India, 1857–1947, 2nd edition, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. xvi, 385, ISBN 0-19-568430-3

- Tomlinson, B. R. (1993), The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970 (The New Cambridge History of India, III.3), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press., ISBN 0-521-58939-8

Further reading

- Ambirajan, S. (1976), "Malthusian Population Theory and Indian Famine Policy in the Nineteenth Century", Population Studies, 30 (1): 5–14, doi:10.2307/2173660, JSTOR 2173660, PMID 11630514

- Arnold, David; Moore, R. I. (1991), Famine: Social Crisis and Historical Change (New Perspectives on the Past), Wiley-Blackwell. Pp. 164, ISBN 0-631-15119-2

- Bhatia, B. M. (1991), Famines in India: A Study in Some Aspects of the Economic History of India With Special Reference to Food Problem, 1860–1990, Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division. Pp. 383, ISBN 81-220-0211-0

- Chakrabarti, Malabika (2004), The Famine of 1896–1897 in Bengal: Availability Or Entitlement, New Delhi: Orient Longmans. Pp. 541, ISBN 81-250-2389-5

- Dutt, Romesh Chunder (2005) [1900], Open Letters to Lord Curzon on Famines and Land Assessments in India, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd (reprinted by Adamant Media Corporation), ISBN 1-4021-5115-2

- Dyson, Tim (1991b), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part II", Population Studies, 45 (2): 279–297, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145446, JSTOR 2174784, PMID 11622922

- Famine Commission (1880), Report of the Indian Famine Commission, Part I, Calcutta

- Hall-Matthews, David (2008), "Inaccurate Conceptions: Disputed Measures of Nutritional Needs and Famine Deaths in Colonial India", Modern Asian Studies, 42 (1): 1–24, doi:10.1017/S0026749X07002892

- Klein, Ira (1973), "Death in India, 1871–1921", The Journal of Asian Studies, 32 (4): 639–659, doi:10.2307/2052814, JSTOR 2052814

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (1983), "Famines, Epidemics, and Population Growth: The Case of India", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 14 (2): 351–366, doi:10.2307/203709, JSTOR 203709

- Washbrook, David (1994), "The Commercialization of Agriculture in Colonial India: Production, Subsistence and Reproduction in the 'Dry South', c. 1870–1930", Modern Asian Studies, 28 (1): 129–164, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00011720, JSTOR 312924