Indian Shaker Church

The Indian Shaker Church is a Christian denomination founded in 1881 by Squaxin shaman John Slocum and his wife Mary Slocum in Washington state. The Indian Shaker Church is a unique blend of American Indian, Catholic, and Protestant beliefs and practices.

The Indian Shakers are unrelated to the Shakers of New England (United Society of Believers) and are not to be confused with the Native American Church.

History and practices

As tradition tells, John Slocum (Squ-sacht-um) had died from sickness in 1881 when he revived during his wake reporting a visit to heaven, where he was told by an angel that, "you've been a pretty bad Indian", and where he received instructions to start a new religion.[1] When Slocum became ill again several months later, his wife, Mary, began to shake and tremble uncontrollably in prayer. Soon afterward, Slocum recovered and his healing was attributed to Mary's convulsions.[2] The religion is thus named for the shaking of members during religious congregations.[3] The shaking is reported to have healing powers.[4]

The story is told that Mary had sent for a casket. John was dead. The casket was brought by canoe, down the river. The casket was just coming around the bend in the river when John revived. ... and told the people he had met Jesus and what they were to do.

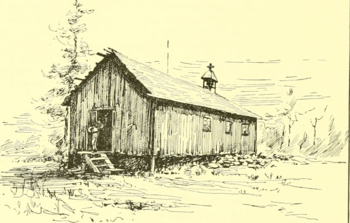

The first church was built at Mud Bay outside Olympia, Washington near the homes of church co-founders and brothers Mud Bay Louie and Mud Bay Sam.[5][6]

Indian Shakers originally rejected the Bible and all other written scriptures and instead relied on direct communication between God and the individual. Such Shakers believe that the experience of the Gospel does not require a book, but rather is encoded in the mind and soul in accordance with the will of God. The religion began to be practiced by many unrelated peoples along the Northwest Coast of North America, such as the Klallam, Quinault, Lower Chehalis, Yakama, Hoh, Quileute, Wiyot, Yurok, and Hupa, among others.

Practices reflecting Catholic influence include the use of hand-held candles, the ringing of individual hand bells (to a very loud volume), and the sign of the cross (usually repeated three times). Protestant influence is shown in public testifying and confession of shortcomings. Native elements include brushing or stroking to remove evil influence, counter-clockwise movement of service participants around the room (often with loud stomping), and spontaneous reception of songs from the spirit. Church members are expected to refrain from using alcohol and tobacco. Carefulness, kindness, and supplication to God for help are emphasized.

The new religion encountered much opposition and hostility from Euro-Americans. As had happened with the Ghost Dance, there was much misunderstanding and Anglos feared an Indian uprising. For a time, all Indian religious practices were banned by law and the Indian Shakers were included. Many members were imprisoned and chained for their practices. Powell et al. (1976) show two notices posted by the US Indian Service at Quileute Reservation:

Notice to the Shakers: You are hereby permitted to hold meetings ... under the following conditions: on Sundays not longer than three (3) hours at one time and on Wednesdays not longer than two (2) hours at one time. The following REGULATIONS to be observed: 1st, Keep windows or a door open during all meetings. 2nd, Use only one bell to give signals. Not continuous ringing. 3rd, Do not admit school children at night meetings. It has been reported ... that there are some women who are violating the Rules ... and that they shake at all hours of the day and night. You will therefore tell the women quietly to stop shaking at any other times than the times specified in the rules ... If they do not stop, ... you will lock them up until they agree to stop. Shaking of the sick must not be allowed ... We do not want any trouble in this matter if it is possible to avoid it; but that 'continual and private shaking' must be stopped.[lower-alpha 1]

In the 1960s, a break occurred among Indian Shakers in which one "conservative" faction continued to reject written religious material while another "progressive" faction was more tolerant of the use of the Bible and other written material.

Indian Shakers continue to practice on the Northwest Coast in Washington, Oregon, California, and British Columbia.

References

- Ruby, p. 3

- Francis, pp. 115-16.

- Ruby, p. 85

- Ruby, p. 81

- Steele 1957, p. 11.

- Mooney 1896, pp. 754 and 758.

- Powell & Jensen 1976.

- Bright 1984.

Bibliography

- Bright, William (1984), "The virtues of illiteracy", American Indian linguistics and literature, Berlin: Mouton Publishers, pp. 149–159

- Francis, John (2011). The Ragged Edge of Silence: Finding Peace in a Noisy World. Washington, DC: National Geographic Books. ISBN 9781426207235. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Mooney, James (1896), "The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890", Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1892–1893, U.S. Government Printing Office

- Powell, Jay; Jensen, Vickie (1976), Quileute: An introduction to the Indians of La Push, Seattle: University of Washington Press

- Ruby, Robert H.; & Brown, John A. (1996). John Slocum and the Indian Shaker Church. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2865-8.

- Steele, E.N. (1957), The rise and decline of the Olympia oyster (PDF), Elma, Washington: Fulco Publications, doi:10.5962/bhl.title.6544

Further reading

- Amoss, Pamela T. (1990). The Indian Shaker Church. In W. Suttles (Ed.), Northwest Coast. Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 7). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Barnett, H. G. (1957). Indian Shakers: A messianic cult of the Pacific Northwest. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Castile, George P. (1982). The 'Half-Catholic' movement: Edwin and Myron Eells and the rise of the Indian Shaker Church. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 73, 165-174.

- Eells, Myron. (1886). Ten years of missionary work among the Indians at Skokomish, Washington Territory, 1874-1884 (pp. 180–237). Boston.

- Fredson, Jean T. (1960). Religion of the Shakers. In H. Deegan (Ed.), History of Mason County Washington. Shelton, WA.

- Giovannetti, Joseph M. (1994). Indian Shaker Church. In Native America in the twentieth century: An encyclopedia (pp. 266–267). New York: Garland Publishing.

- Gunter, Erna. (1977). The Shaker Religion of the Northwest. In J. A. Halseth & B. A. Glasrud (Eds.), The Northwest mosaic: Minority conflicts in Pacific Northwest history. Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing Company.

- Harmon, Alexandra. (1999). Indians in the making: Ethnic relations and Indian identities around Puget Sound (pp. 125–130). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Harmon, Ray. (1971). Indian Shaker Church, The Dalles. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 72, 148-158.

- Ober, Sarah E. (1910). A new religion among the West Coast Indians. The Overland Monthly, 56 (July–December).

- Sackett, Lee. (1973). The Siletz Indian Shaker Church. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 64 (July), 120-26.

- Valory, Dale. (1966). The focus of Indian Shaker healing. The Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers (No. 35). Berkeley: Kroeber Anthropological Society.

- From the University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections - American Indians of the Pacific Northwest Collection:

- The Siletz Indian Shaker Church

- The "Half-Catholic" movement: Edwin and Myron Eells and the rise of the Indian Shaker Church

- The Indian Connection: Judge James Wickersham and the Indian Shakers (1990)

- The Present Status and Probable Future of the Indians of Puget Sound (1914) (see: pp. 18–20)

- The Swinomish People and Their State (1936) (see: pp. 293–295)