Indian Mounds Park (Saint Paul, Minnesota)

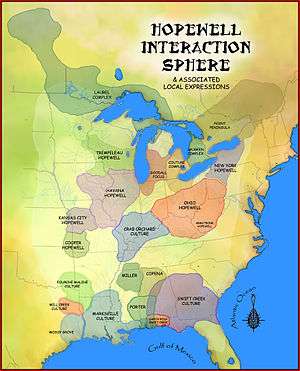

Indian Mounds Regional Park is a public park in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States, featuring six prehistoric Native American burial mounds overlooking the Mississippi River. The oldest mounds were constructed 1,500–2,000 years ago by people of the Hopewell tradition. Later the Dakota people interred their dead there as well.[2] At least 31 more mounds were destroyed by development in the late 19th century. They were the tallest Native American mounds in Minnesota or Wisconsin (except for the unique 45-foot (14 m) Grand Mound outside International Falls, Minnesota), and comprise one of the northwesternmost Hopewellian sites in North America.[4] Indian Mounds Regional Park is a component of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, a unit of the National Park System. The Mounds Group is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[5] The 2014 nomination document provides a description of the archaeology and the context.[6]

| Indian Mounds Regional Park | |

|---|---|

Two of the park's prehistoric burial mounds | |

Location of Indian Mounds Regional Park in Minnesota  Indian Mounds Park (Saint Paul, Minnesota) (the United States) | |

| Location | Ramsey, Minnesota, United States |

| Coordinates | 44°56′44″N 93°3′13″W |

| Area | 79 acres (32 ha) |

| Elevation | 876 ft (267 m)[1] |

| Established | 1893[2] |

| Governing body | Saint Paul Parks and Recreation |

Indian Mounds Park Mound Group | |

| Location | 1075 Mounds Boulevard, Saint Paul, Minnesota |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 44°56′45″N 93°3′24″W |

| Area | 3.6 acres (1.5 ha) |

| Built | c. 1000 BCE–1837 |

| NRHP reference No. | 14000140[3] |

| Added to NRHP | April 11, 2014 |

Early history

There were once at least 18 mounds, plus another 19 a short distance to the northwest directly above Carver's Cave.[7] The mounds of the second group were all quite small, under two feet (0.6 m) high.[4] Anthropologists ascribe the oldest mounds to mound builders of the Hopewell Tradition, but later cultures also added to the mounds.[8] No evidence of habitation has been found among the mounds, so the builders lived elsewhere nearby, probably in a village below the bluff.[4]

The Dakota village of Kaposia was established at the foot of the bluff before 1600 CE. English explorer Jonathan Carver described the site in 1766 and visited the recent burial of a Dakota leader among the mounds.[9]

Excavation

Burial mounds were first excavated by Edward Duffield Neill in 1856, followed by a dig sponsored by the Minnesota Historical Society.[8] In 1879 Theodore H. Lewis conducted a more thorough investigation.[9] Both mound groups revealed a variety of burial styles. At least three mounds were built around log tombs, and two others contained multiple cists made of limestone slabs.[8] Hopewellian grave goods included nothing but mussel shells in the simplest and most common burials, but projectile points, perforated bear teeth, and copper ornaments in others.[8] One burial contained a child's skull with clay pressed onto it in an apparent recreation of the individual's features.[4] No other such death masks have ever been documented in contemporaneous Native American burials.[8] Human remains in funeral bundles found in the upper parts of some mounds were interpreted as burials from more recent cultures.[8]

The early archaeologists exhumed around 20 mostly complete skeletons (though many were missing their skulls) and fragments of perhaps another 30 individuals.[4] Since the burials were likely made over several generations, only a relatively small number of individuals were marked with mounds. Who was chosen for mound burial, and what was done with the rest of the dead, are unknown.[4]

These 19th-century archaeologists, "some of them amateurs in their day, all of them amateurs by today's standards,"[4] may have destroyed as much information as they preserved. Theodore Lewis was a sophisticated researcher for his time, but worked hastily — once excavating seven mounds in one day — and didn't make detailed descriptions of his finds.[10] Most of his artifacts have since been lost, so it is impossible for modern archaeologists to identify more certainly the cultural affiliations and periods of the various mound users.[10]

In the late 19th century the bluff-face was successively demolished to widen the rail yard at its foot, destroying several mounds as well as the outer chamber of Carver's Cave.[11] In a time "when digging into a mound was a respectable Sunday pastime,"[4] locals also repeatedly looted and vandalized the mounds.[7]

The mound site received a modern archaeological field survey in 1981 from the Minnesota Historical Society.[7]

Park development

Interest in preserving the open land along the blufftop arose in the 1880s as the local population boomed. The City of Saint Paul struggled to buy the land from its various private owners, as some proved unwilling to sell and others sold to real estate speculators first. Enough property was assembled by 1896 for the city to begin landscaping and building visitor amenities.[9] In sharp contrast to modern practices, 11 mounds were leveled on the grounds that they blocked the view of the river.[10] Only the six largest mounds were left.[7]

The park was expanded to 82 acres (33 ha) in 1900, and in 1914 a still-standing brick pavilion was built to house a refreshment stand, restrooms, and space for open-air concerts.[9]

Indian Mounds Regional Park received a major restoration in the 1980s using state and federal funds for developing the Great River Road. The pavilion was restored, new amenities added, and houses and a road were removed. The Dayton's Bluff Community Council raised funds and placed decorative fences around the mounds as a protection from visitors.[9]

Airway beacon

Adjacent to the mounds is a 110-foot-high (34 m) airway beacon built in 1929 as part of a national network to aid pilots delivering airmail.[9] The Indian Mounds Park "Airway" Beacon, as it is officially known, helped mark the route between Saint Paul and Chicago. There were once over 600 of these beacons, but electronic navigation systems rendered them obsolete. Restored to its historical black and chrome-yellow color scheme in the mid-1990s, the Indian Mounds Park beacon has been kept operational and flashes its rotating light every 5 seconds.[12] It is one of the few remaining airway beacons in the United States.[9][12]

Recreation

Currently Indian Mounds Regional Park provides two electrified picnic shelters which can be rented by private groups. Other visitor amenities in the park include a playground, barbecue grills, fire rings, restrooms and a drinking fountain, paved trails, and a ball field and tennis courts.[8]

See also

References

- "Indian Mounds Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1980-01-11. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- "Indian Mounds Park". Mississippi National River and Recreation Area: Plan Your Visit. National Park Service. 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2001-04-21.

- http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/feature/places/14000140.htm

- Nelson, Paul D. (2008-05-20). "St. Paul's Indian Burial Mounds". Staff Publications. Paper 1. Retrieved 2001-04-21.

- Anderson, Jim (13 July 2014). "St. Paul mounds find their ground on National Register of Historic Places". Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/14000140.pdf

- "The Indian Mounds Park Site". From Site to Story: The Upper Mississippi's Buried Past. The Institute for Minnesota Archaeology. 1999-06-29. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- Woitas, Kay. "Indian Mounds Park (Regional)". City of St. Paul. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- Trimble, Steve (2000-07-02). "A Short History of Indian Mounds Park". Dayton's Bluff District Four Community Council. Archived from the original on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- Garvey, Dennis W. "Indian Mounds Park and Dayton's Bluff Mound Groups". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- "Lower Phalen Creek". Archived from the original on 2005-04-29. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- Cosimini, Greg (1999-07-09). "Indian Mounds Park "Airway" Beacon". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 2008-01-24. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indian Mounds Park (Saint Paul, Minnesota). |