Inch House, Edinburgh

Inch House, a former country house situated within Inch Park in Edinburgh, Scotland is a Grade A listed building.[1] The oldest part, a Scottish vernacular L-plan tower house, dates from the early 17th century. From 1660 it was owned by the Gilmour family, who arranged for additions and extensions to the house in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was sold to the then Edinburgh Corporation in 1945. Since then it has been used as a primary school and more recently as a community centre.

| Inch House | |

|---|---|

Inch House, south-east facade. The original tower is on the right and the west wing is on the left. | |

| Coordinates | 55.924808°N 3.158817°W |

| Built | 1617-1892 |

| Architect | George Smith (1841) MacGibbon & Ross (1891) |

| Owner | City of Edinburgh Council |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Designated | 14 July 1966 |

| Reference no. | LB28078 |

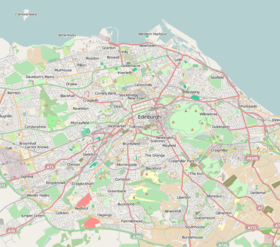

Location of Inch House in Edinburgh | |

Origins and ownership

The word ‘Inch’ derives from the Scots Gaelic ‘innis’ which can mean either 'island' or a dry area within marshland or a river meadow.[2][3] This suggests that the land on which it stands was originally dry land in the flood plain of the nearby Braid Burn.[4] The lands of Nether Liberton on which Inch House now stands were granted to the monks of Holyrood Abbey from the mid-15th century. The lands then came into the possession of Alexander Forrester, 6th of Corstorphine, confirmed by King James V in the lands and Barony of Corstorphine, which at that time included Nether Liberton.[5] It is possible that this family built an early tower on the site.[6] The present house was originally built as an L- shaped tower house in the Scottish vernacular style consisting of three floors and an attic.[7] There have been additions at different times in its history. The original house was built for James Winram (d.1632), Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland[8] who passed it to his son George Winram (Lord Liberton).[9] A supporter of the Covenanters, he died in 1650 from wounds sustained at the Battle of Dunbar where he fought against Oliver Cromwell's army.[9] After the battle the victorious Cromwell took over Inch House. In 1660 the property was bought by Sir John Gilmour of Craigmillar, Lord President of the Court of Session, and it remained in the hands of the Gilmour family until 1945. The last residents were Sir Robert Gordon Gilmour and his wife Lady Susan Gilmour (née Lygon) (1870 – 1962). Their son, Sir John Little Gilmour (1899-1977) sold the estate and the house to the then City of Edinburgh Council in 1946.[6] It was then used as a primary school with some of the children moving to the newly built Liberton Primary School in 1956. The remaining pupils were those of St John Vianney Roman Catholic Primary School, and these pupils finally moved to a new school in 1968. The house subsequently became a community centre.[6]

.jpg)

17th century

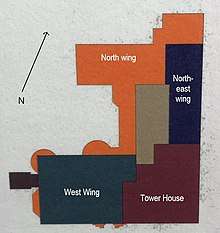

In 1607 James Winram (father of George Winram, Lord Liberton) bought the Nether Liberton lands which included the Inch estate. He commissioned the building of Inch House which was originally an L shaped tower, completed in 1617.[10] The doorway with the date 1617 embossed on the lintel is still present, but due to later alterations, is now entirely internal. New features were added in 1634. A large doorway was built in the internal angle of the ‘L’ to form a grand entrance leading to a wide spiral staircase. Also in 1634 a two-storey north-east wing was added to the tower.[7]

18th and 19th centuries

Sir John Gilmour of Craigmillar had also bought Craigmillar Castle which he made his home while renting out Inch House. His successors, the Gilmour baronets of Craigmillar, did the same. During the Jacobite rising of 1745 Government forces were stationed in Inch House.[11] A west wing was added late in the 18th century.[12] After the death of Sir Alexander Gilmour, 3rd Baronet in 1792, the house was modernised, and the Gilmour family lived there from 1796. Further modifications took place in 1813 and in 1834, including moving the main entrance to the south side of the building. Sir Robert Gordon Gilmour (1857-1939) inherited the house and in 1889 married Lady Susan Lygon (1870-1962), and they planned a major series of internal and external alterations which took place between 1890 and 1892. They commissioned the leading historical architectural firm MacGibbon and Ross, who had published a major historical survey of Scotland's towers and stately homes entitled The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the twelfth to the eighteenth centuries,[13] They were asked by the Gordon Gilmours to make the entrance to the house grander and more impressive and to make the house more comfortable for late 19th century living. MacGibbon and Ross achieved this while retaining much of the earlier historic character of the building. The modernisation and embellishment included enhancing the main entrance by creating an elaborate pilastered and pedimented porch, above which is inscribed the Gilmour family motto ‘Nil Penna Sed Usus’ ('the practice not the penmanship'). This doorway led to a grand entrance hallway and staircase. A fire destroyed this staircase in 1979, and it was replaced with one in a similar style. There were also external and internal modifications made to the 18th century west wing. The internal modifications included enlarging ground floor and first floor rooms by removing internal walls, enlarging windows, creating west-facing bay windows and stripping the plasterwork in the ground floor room of the tower to make the original stonework a feature. Externally the west wing was made to look grander with the addition of angle turrets and dormer windows.[14] There was further major expansion of the building at this time with the addition of a north wing which resulted in the formation of an inner courtyard. The 1890 modifications also included building a chimney on the original tower building to vent a very large fireplace created in the ground floor.[1][14]

20th century

Inch House was bought in 1946 by the then Edinburgh Corporation. It was used as a primary school, and the courtyard was roofed over to form a dining room. Some pupils transferred in 1956 to the nearby purpose built Liberton Primary School. The remaining primary school, St John Vianney Roman Catholic Primary school, was transferred to a newly built school of the same name in nearby Ivanhoe Crescent in 1968.[6] The building has since been a community centre. A brutalist-style fire escape was added to the wall of the west wing, ruining the west facade around 1970. The Inch Community Centre uses many of the rooms in the house including general purpose rooms, music rehearsal rooms, areas for arts and crafts, a photography room, a kitchen and an office.[15] The centre runs a variety of activities, classes and clubs.[15][16]

Description

Inch House is located in the south of Edinburgh, two miles south east of the city centre. The district is now known as The Inch and contains Inch Park and the Inch housing development. Access from the west is by a roadway off Gilmerton Road, through the original west gate of the property. Access from the east is from Old Dalkeith Road by a roadway which skirts the northern boundary of the City of Edinburgh Council's Inch plant nursery and horticultural training centre, formerly the walled garden of Inch House. Originally a tower house, several major additions have been made to the building over the centuries.[13]

The Seventeenth century tower house

The original L-shaped tower dates from 1617. The wide staircase added at the re-entrant angle of the tower in 1634 was an unusual feature in towers of this period. The large doorway, created on the north side of the tower at the same time, is now internal as a result of later additions. The lintel carries the date 1617, the motto "Blessed be God" above the initials James Winram (IW) and his wife Jean Swinton (JS). The ground floor room, originally a vault or cellar, occupies the entire breadth of the tower. It has a barrel vaulted ceiling, and the original stonework is now revealed as a feature. There are smaller rooms on the second and third floors from where a turret stair leads to a roof area which commands panoramic views.[7][8][12]

The north east wing

This three storey extension, added in 1634, connects the tower block to the north wing. On the west external wall above two windows are the initials 'IW' and 'IS' again representing James Winram and Jean Swinton. The date 1634 is inscribed on one of the dormers.[10][13]

The west wing

The two storey west wing was built in the 1790s and was modified internally and externally in 1891-92. The large room on the ground floor is of a similar size to the equivalent room in the tower house, while the first floor also has a large room of similar size along the length of the wing. Both these rooms have large bay windows added in 1892. Third floor rooms are smaller and feature dormer windows added in 1891-92.[10][13]

References

- "Inch House, Glenallan Drive, Old Dalkeith Road And Gilmerton Road (LB28078)". portal.historicenvironment.scot. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- "innis - Scottish Gaelic-English Dictionary". Glosbe. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- "Gaelic Place-Names: 'Eilean' and 'Innis'". The Bottle Imp. 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- Old Edinburgh Club (1917). The book of the Old Edinburgh Club. Edinburgh : The Old Edinburgh Club. pp. 3.

- "Forrester of Corstorphine, Lord (S, 1633)". www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- "Inch House - A Brief History - South Edinburgh Net :: South Edinburgh's Community Network". www.southedinburgh.net. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- Sweet, Andy. "Inch House | Castle in Edinburgh, Midlothian | Stravaiging around Scotland". Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- Gifford, John; McWilliam, Colin; Wilson, Christopher; Walker, David (1984). The Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. pp. 585–586. ISBN 014071068X. OCLC 13328161.

- "Winram [Windrahame], George, of Liberton, Lord Liberton (d. 1650), politician and judge | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". www.oxforddnb.com. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29749. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- Coventry, Martin (2000). The Castles of Scotland: A Comprehensive Reference and Gazetteer to More Than 2700 Castles and Fortified Cities. Musselburgh: Goblinshead. ISBN 978-1-899874-27-9.

- Nimmo, Ian (1996). Edinburgh’s Green Heritage Recreation : Discovering the Capital's Parks, Woodlands and Wildlife. Edinburgh: The City of Edinburgh Council. pp. 77, 78. ISBN 0952521954.

- The City of Edinburgh Council. "Gardens and Designed Landscapes site reports | The City of Edinburgh Council". www.edinburgh.gov.uk. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- MacGibbon, David; Ross, Thomas (1887). The castellated and domestic architecture of Scotland from the twelfth to the eighteenth century. Volume 3. Edinburgh: David Douglas. pp. 528-531.

- "Inch House, Glenallan Drive, Old Dalkeith Road And Gilmerton Road (LB28078)". portal.historicenvironment.scot. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- "Inch Community Education Centre". www.evocredbook.org.uk. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- "Inch Community Centre - South Edinburgh Net :: South Edinburgh's Community Network". www.southedinburgh.net. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

Further reading

- Coventry, Martin (2001) The Castles of Scotland. Goblinshead, Musselburgh

- McKean, Charles, with David Walker (1982) Edinburgh: An Illustrated Architectural Guide. RIAS Publications, Edinburgh

- Wallace, Joyce M. (1998) The Historic Houses of Edinburgh. John Donald Publishers Ltd., Edinburgh