International Chemical Identifier

The IUPAC International Chemical Identifier (InChI /ˈɪntʃiː/ IN-chee or /ˈɪŋkiː/ ING-kee) is a textual identifier for chemical substances, designed to provide a standard way to encode molecular information and to facilitate the search for such information in databases and on the web. Initially developed by IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) and NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) from 2000 to 2005, the format and algorithms are non-proprietary.

| Developer(s) | InChI Trust |

|---|---|

| Initial release | April 15, 2005[1][2] |

| Stable release | 1.05

/ March 2017 |

| Operating system | Microsoft Windows and Unix-like |

| Platform | IA-32 and x86-64 |

| Size | 4.3 MB |

| Available in | English |

| License | IUPAC / InChI Trust Licence |

| Website | https://www.inchi-trust.org/ |

The continuing development of the standard has been supported since 2010 by the not-for-profit InChI Trust, of which IUPAC is a member. The current software version is 1.05 and was released in January 2017.

Prior to 1.04, the software was freely available under the open-source LGPL license,[3] but it now uses a custom license called IUPAC-InChI Trust License.[4]

Overview

The identifiers describe chemical substances in terms of layers of information — the atoms and their bond connectivity, tautomeric information, isotope information, stereochemistry, and electronic charge information.[5] Not all layers have to be provided; for instance, the tautomer layer can be omitted if that type of information is not relevant to the particular application.

InChIs differ from the widely used CAS registry numbers in three respects: 1) they are freely usable and non-proprietary; 2)they can be computed from structural information and do not have to be assigned by some organization; and 3) most of the information in an InChI is human readable (with practice).

InChIs can thus be seen as akin to a general and extremely formalized version of IUPAC names. They can express more information than the simpler SMILES notation and differ in that every structure has a unique InChI string, which is important in database applications. Information about the 3-dimensional coordinates of atoms is not represented in InChI; for this purpose a format such as PDB can be used.

The InChI algorithm converts input structural information into a unique InChI identifier in a three-step process: normalization (to remove redundant information), canonicalization (to generate a unique number label for each atom), and serialization (to give a string of characters).

The InChIKey, sometimes referred to as a hashed InChI, is a fixed length (27 character) condensed digital representation of the InChI that is not human-understandable. The InChIKey specification was released in September 2007 in order to facilitate web searches for chemical compounds, since these were problematic with the full-length InChI.[6] Unlike the InChI, the InChIKey is not unique: though collisions can be calculated to be very rare, they happen.[7]

In January 2009 the final 1.02 version of the InChI software was released. This provided a means to generate so called standard InChI, which does not allow for user selectable options in dealing with the stereochemistry and tautomeric layers of the InChI string. The standard InChIKey is then the hashed version of the standard InChI string. The standard InChI will simplify comparison of InChI strings and keys generated by different groups, and subsequently accessed via diverse sources such as databases and web resources.

Format and layers

| Internet media type |

chemical/x-inchi |

|---|---|

| Type of format | chemical file format |

Every InChI starts with the string "InChI=" followed by the version number, currently 1. This is followed by the letter S for standard InChIs, which is a fully standardized InChI flavor maintaining the same level of attention to structure details and the same conventions for drawing perception. The remaining information is structured as a sequence of layers and sub-layers, with each layer providing one specific type of information. The layers and sub-layers are separated by the delimiter "/" and start with a characteristic prefix letter (except for the chemical formula sub-layer of the main layer). The six layers with important sublayers are:

- Main layer

- Chemical formula (no prefix). This is the only sublayer that must occur in every InChI.

- Atom connections (prefix: "c"). The atoms in the chemical formula (except for hydrogens) are numbered in sequence; this sublayer describes which atoms are connected by bonds to which other ones.

- Hydrogen atoms (prefix: "h"). Describes how many hydrogen atoms are connected to each of the other atoms.

- Charge layer

- proton sublayer (prefix: "p" for "protons")

- charge sublayer (prefix: "q")

- Stereochemical layer

- double bonds and cumulenes (prefix: "b")

- tetrahedral stereochemistry of atoms and allenes (prefixes: "t", "m")

- type of stereochemistry information (prefix: "s")

- Isotopic layer (prefixes: "i", "h", as well as "b", "t", "m", "s" for isotopic stereochemistry)

- Fixed-H layer (prefix: "f"); contains some or all of the above types of layers except atom connections; may end with "o" sublayer; never included in standard InChI

- Reconnected layer (prefix: "r"); contains the whole InChI of a structure with reconnected metal atoms; never included in standard InChI

The delimiter-prefix format has the advantage that a user can easily use a wildcard search to find identifiers that match only in certain layers.

| Structural formula | standard InChI |

|---|---|

InChI=1S/C2H6O/c1-2-3/h3H,2H2,1H3 | |

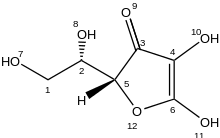

L-ascorbic acid |

InChI=1S/C6H8O6/c7-1-2(8)5-3(9)4(10)6(11)12-5/h2,5,7-8,10-11H,1H2/t2-,5+/m0/s1 |

InChIKey

The condensed, 27 character InChIKey is a hashed version of the full InChI (using the SHA-256 algorithm), designed to allow for easy web searches of chemical compounds.[6] The standard InChIKey is the hashed counterpart of standard InChI. Most chemical structures on the Web up to 2007 have been represented as GIF files, which are not searchable for chemical content. The full InChI turned out to be too lengthy for easy searching, and therefore the InChIKey was developed. There is a very small, but nonzero chance of two different molecules having the same InChIKey, but the probability for duplication of only the first 14 characters has been estimated as only one duplication in 75 databases each containing one billion unique structures. With all databases currently having below 50 million structures, such duplication appears unlikely at present. A recent study more extensively studies the collision rate finding that the experimental collision rate is in agreement with the theoretical expectations.[8]

InChIKey consists of hyphen-separated three parts, of 14, 10 and one character(s), respectively, like XXXXXXXXXXXXXX-YYYYYYYYYY-Z. The first 14 characters result from a hash of the connectivity information of the InChI. The second part consists of 8 characters resulting from a hash of the remaining layers of the InChI, a single character indicating the kind of InChIKey and a single character indicating the version of InChI used. At last, a single character indicates protonation.[9]

Example

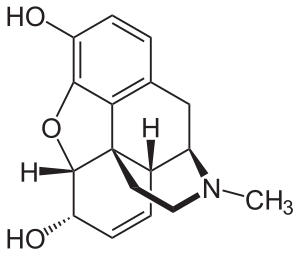

Morphine has the structure shown on the right. The standard InChI for morphine is InChI=1S/C17H19NO3/c1-18-7-6-17-10-3-5-13(20)16(17)21-15-12(19)4-2-9(14(15)17)8-11(10)18/h2-5,10-11,13,16,19-20H,6-8H2,1H3/t10-,11+,13-,16-,17-/m0/s1

and the standard InChIKey for morphine is BQJCRHHNABKAKU-KBQPJGBKSA-N.[10]

InChI resolvers

As the InChI cannot be reconstructed from the InChIKey, an InChIKey always needs to be linked to the original InChI to get back to the original structure. InChI Resolvers act as a lookup service to make these links, and prototype services are available from National Cancer Institute, the UniChem service at the European Bioinformatics Institute, and PubChem. ChemSpider has had a resolver until July 2015 when it was decommissioned.[11]

Name

The format was originally called IChI (IUPAC Chemical Identifier), then renamed in July 2004 to INChI (IUPAC-NIST Chemical Identifier), and renamed again in November 2004 to InChI (IUPAC International Chemical Identifier), a trademark of IUPAC.

Continuing development

Scientific direction of the InChI standard is carried out by the IUPAC Division VIII Subcommittee, and funding of subgroups investigating and defining the expansion of the standard is carried out by both IUPAC and the InChI Trust. The InChI Trust funds the development, testing and documentation of the InChI. Current extensions are being defined to handle polymers and mixtures, Markush structures, reactions[12] and organometallics, and once accepted by the Division VIII Subcommittee will be added to the algorithm.

Adoption

The InChI has been adopted by many larger and smaller databases, including ChemSpider, ChEMBL, Golm Metabolome Database, OpenPHACTS, and PubChem.[13] However, the adoption is not straightforward, and many databases show a discrepancy between the chemical structures and the InChI they contain, which is a problem for linking databases.[14]

See also

- Molecular Query Language

- Simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES)

- Molecule editor

- SYBYL Line Notation

- Bioclipse generates InChI and InChIKeys for drawn structures or opened files

- the Chemistry Development Kit uses JNI-InChI to generate InChIs, can convert InChIs into structures, and generate tautomers based on the InChI algorithms

Notes and references

- "IUPAC International Chemical Identifier Project Page". IUPAC. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- Heller, S.; McNaught, A.; Stein, S.; Tchekhovskoi, D.; Pletnev, I. (2013). "InChI - the worldwide chemical structure identifier standard". Journal of Cheminformatics. 5 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1758-2946-5-7. PMC 3599061. PMID 23343401.

- McNaught, Alan (2006). "The IUPAC International Chemical Identifier:InChl". Chemistry International. 28 (6). IUPAC. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- http://www.inchi-trust.org/download/104/LICENCE.pdf

- Heller, S.R.; McNaught, A.; Pletnev, I.; Stein, S.; Tchekhovskoi, D. (2015). "InChI, the IUPAC International Chemical Identifier". Journal of Cheminformatics. 7: 23. doi:10.1186/s13321-015-0068-4. PMC 4486400. PMID 26136848.

- "The IUPAC International Chemical Identifier (InChI)". IUPAC. 5 September 2007. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- E.L. Willighagen (17 September 2011). "InChIKey collision: the DIY copy/pastables". Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- Pletnev, I.; Erin, A.; McNaught, A.; Blinov, K.; Tchekhovskoi, D.; Heller, S. (2012). "InChIKey collision resistance: An experimental testing". Journal of Cheminformatics. 4 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/1758-2946-4-39. PMC 3558395. PMID 23256896.

- "Technical FAQ - InChI Trust". inchi-trust.org. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "InChI=1/C17H19NO3/c1-18..." Chemspider. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- InChI Resolver, 27 July 2015, http://www.chemspider.com/InChiResolverDecommissioned.aspx

- Grethe, Guenter; Blanke, Gerd; Kraut, Hans; Goodman, Jonathan M. (9 May 2018). "International chemical identifier for reactions (RInChI)". Journal of Cheminformatics. 10 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s13321-018-0277-8. PMC 4015173. PMID 24152584.

- Warr, W.A. (2015). "Many InChIs and quite some feat". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 29 (8): 681–694. Bibcode:2015JCAMD..29..681W. doi:10.1007/s10822-015-9854-3. PMID 26081259.

- Akhondi, S. A.; Kors, J. A.; Muresan, S. (2012). "Consistency of systematic chemical identifiers within and between small-molecule databases". Journal of Cheminformatics. 4 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/1758-2946-4-35. PMC 3539895. PMID 23237381.

External links

Wikidata has the property:

|

- IUPAC InChI site

- Description of the canonicalization algorithm

- Googling for InChIs a presentation to the W3C.

- InChI Release 1.02 InChI final version 1.02 and explanation of Standard InChI, January 2009

- NCI/CADD Chemical Identifier Resolver Generates and resolves InChI/InChIKeys and many other chemical identifiers

- PubChem online molecule editor that supports SMILES/SMARTS and InChI

- ChemSpider Compound APIs ChemSpider REST API that allows generation of InChI and conversion of InChI to structure (also SMILES and generation of other properties)

- MarvinSketch from ChemAxon, implementation to draw structures (or open other file formats) and output to InChI file format

- BKchem implements its own InChI parser and uses the IUPAC implementation to generate InChI strings

- CompoundSearch implements an InChI and InChI Key search of spectral libraries

- SpectraBase implements an InChI and InChI Key search of spectral libraries

- JSME is a free JavaScript based molecular editor that generates InChI and InChI Key in a web browser, which allows for easy web searches of chemical compounds