Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (23 March 1899 – 10 March 1998) was a German avant-garde and commercial photographer who produced pioneering monochrome images during the inter-war era.

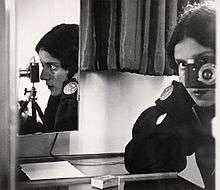

Ilse Bing | |

|---|---|

Self portrait in 1931 | |

| Born | 23 March 1899 |

| Died | 10 March 1998 (aged 98) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse(s) | |

Early life

Bing was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Frankfurt, Germany in 1899.[1] She was well-educated, with particular attention to the arts and music.[2] Bing initially enrolled at the University of Frankfurt to study mathematics in 1920, but eventually moved to Vienna to study art history.[2] In 1924, Bing began a doctoral program studying architecture.[1] It was during her time as a doctoral student photographing buildings for her dissertation that Bing developed her lifelong interest in photography.[3] In 1929, inspired by the work of Florence Henri, Bing moved to Paris to work with Henri and other Modernists.[3]

Career

Her move from Frankfurt to the burgeoning avant-garde and surrealist scene in Paris in 1930 marked the start of the most notable period of her career.[3] She produced images in the fields of photojournalism, architectural photography, advertising and fashion, and her work was published in magazines such as Le Monde Illustre, Harper's Bazaar, and Vogue.[1] Respected for her use of daring perspectives, unconventional cropping, use of natural light, and geometries, she also discovered a type of solarisation for negatives independently of a similar process developed by the artist Man Ray.[3]

Her rapid success as a photographer and her position as the only professional in Paris to use an advanced Leica camera earned her the title "Queen of the Leica"[4] from the critic and photographer Emmanuel Sougez. In 1936, her work was included in the first modern photography exhibition held at the Louvre, and in 1937 she traveled to New York City where her images were included in the landmark exhibition "Photography 1839–1937" at the Museum of Modern Art.[4] She remained in Paris for ten years, but in 1940, when Paris was taken by the Germans during World War II, she and her husband who were both Jews, were expelled and interned in separate camps in the South of France. Bing spent six weeks in a camp in Gurs, in the Pyrenees, before rejoining her husband in Marseille, where they waited for nine months for the US visas. They were finally able to leave for America in June 1941.[1] There, she had to re-establish her reputation, and although she got steady work in portraiture, she failed to receive important commissions as in Paris.[1]

When Bing and her husband fled Paris, she was unable to bring her prints and left them with a friend for safekeeping. Following the war, her friend shipped Bing's prints to her in New York, but Bing could not afford the custom fees to claim them all. Some of her original prints were lost when Bing had to choose which prints to keep.[5]

By 1947, Bing came to the realization that New York had revitalized her art. Her style was very different; the softness that characterized her work in the 1930s gave way to hard forms and clear lines, with a sense of harshness and isolation. This was indicative of how Bing’s life and worldview had been changed by her move to New York and the war-related events of the 1940s.[2]

For a short time in the 1950s, Bing experimented with color, but soon gave up photography altogether. She felt the medium was no longer adequate for her, and seemed to have tired of it.[1]

In the mid-1970s, the Museum of Modern Art purchased and showed several of her photographs.[4] This show sparked renewed interest in Bing's work, and subsequent exhibitions included a solo show at the Witkins Gallery in 1976, and a traveling retrospective entitled, ''Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography,''[4][2] organized by the New Orleans Museum of Art. In 1993, the National Arts Club awarded her the first gold medal for photography.[6]

In the last few decades of her life, she wrote poetry, made drawings and collages, and occasionally incorporated bits of photos. She was interested in combining mathematics, words, and images.[3] When she gave up photography in the 1950s, Ilse Bing noted that she had said all she wanted to say with a camera. (Ref NY Times obituary - 1998)

Documentary

Bing was one of three female photographers portrayed in Drei Fotografinnen: Ilse Bing, Grete Stern, Ellen Auerbach, a 1993 documentary by Berlin filmmaker Antonia Lerch.[7]

Public collections

- Art Institute of Chicago[8]

- New Orleans Museum of Art[8]

- Glyndebourne[8]

- Jewish Museum, Berlin[8]

- Jewish Museum (Manhattan)[8]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art[8]

- MOCA Grand Avenue[8]

- Museum Folkwang[8]

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)[8]

- National Gallery of Canada[8]

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam[9]

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art[8]

- Victoria & Albert Museum[8]

References

- webmaster@vam.ac.uk, Victoria and Albert Museum, Online Museum, Web Team. "Ilse Bing Biography". www.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- "Ilse Bing | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- Loke, Margarett (1998-03-15). "Ilse Bing, 98, 1930's Pioneer Of Avant-Garde Photography". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- arts, Roberta Hershenson; Roberta Hershenson writes frequently about the (1986-02-23). "Camera Pioneer Aluted at Icp". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- "Ilse Bing | German-born photographer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- Brozan, Nadine (1993-03-08). "Chronicle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- "Film | Drei Fotografinnen: Ilse Bing, Grete Stern, Ellen Auerbach | absolut MEDIEN". absolutmedien.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- London, ArtFacts.Net Ltd. "Ilse Bing - Biography". www.artfacts.net. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- Collection Rijksmuseum

Further reading

- Barrett, Nancy (1985). Ilse Bing, three decades of photography. New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0894940224. OCLC 469479874.

- Dryansky, Larisa (2006). Ilse Bing: photography through the looking glass. New York: H.N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810955462. OCLC 608305260.

- Reynaud, François (1987). Ilse Bing : Paris 1931-1952. Paris, France: Musée Carnavalet. OCLC 680579906.

- Schmalbach, Hilary (1996). Ilse Bing: Fotografien 1929-1956. Aachen, Germany: Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum Aachen. ISBN 978-3929203127. OCLC 432873363.

- Misselbeck, Reinhold, ed. (1996). 20th Century Photography. Germany: Museum Ludwig Cologne. Taschen. ISBN 978-3822858677. OCLC 680579906.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Greenspoon, Leonard J. (2013). Fashioning Jews: Clothing, Culture, and Commerce. West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557536570. OCLC 1058492422.

- Wilson, Dawn (Winter 2012). "Facing the Camera: Self-portraits of Photographers as Artists". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 70 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6245.2011.01498.x. JSTOR 42635856.

- David, Travis (1987). "In and of the Eiffel Tower". Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. 13 (1): 5–23. JSTOR 4115922.

- Sarah, Kennel (Autumn 2005). "Fantasies of the Street: Emigré Photography in Interwar Paris". History of Photography. 29 (3): 287–300. doi:10.1080/03087298.2005.10442803. JSTOR 4115922.