I-beam

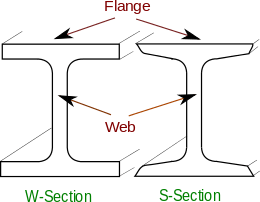

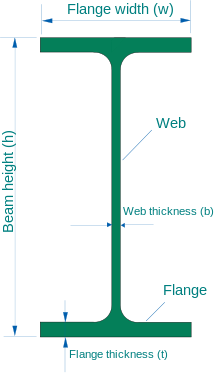

An I-beam, also known as H-beam (for universal column, UC), w-beam (for "wide flange"), universal beam (UB), rolled steel joist (RSJ), or double-T (especially in Polish, Bulgarian, Spanish, Italian and German), is a beam with an I or H-shaped cross-section. The horizontal elements of the I are flanges, and the vertical element is the "web". I-beams are usually made of structural steel and are used in construction and civil engineering.

The web resists shear forces, while the flanges resist most of the bending moment experienced by the beam. The Euler-Bernoulli beam equation shows that the I-shaped section is a very efficient form for carrying both bending and shear loads in the plane of the web. On the other hand, the cross-section has a reduced capacity in the transverse direction, and is also inefficient in carrying torsion, for which hollow structural sections are often preferred.

History

The method of producing an I-beam, as rolled from a single piece of steel, was patented by Alphonse Halbou of the company Forges de la Providence in 1849.[1]

Bethlehem Steel was a leading supplier of rolled structural steel of various cross-sections in American bridge and skyscraper work of the mid-twentieth century.[2] Today, rolled cross-sections have been partially displaced in such work by fabricated cross-sections.

Overview

There are two standard I-beam forms:

- Rolled I-beam, formed by hot rolling, cold rolling or extrusion (depending on material).

- Plate girder, formed by welding (or occasionally bolting or riveting) plates.

I-beams are commonly made of structural steel but may also be formed from aluminium or other materials. A common type of I-beam is the rolled steel joist (RSJ)—sometimes incorrectly rendered as reinforced steel joist. British and European standards also specify Universal Beams (UBs) and Universal Columns (UCs). These sections have parallel flanges, as opposed to the varying thickness of RSJ flanges which are seldom now rolled in the UK. Parallel flanges are easier to connect to and do away with the need for tapering washers. UCs have equal or near-equal width and depth and are more suited to being oriented vertically to carry axial load such as columns in multi-storey construction, while UBs are significantly deeper than they are wide are more suited to carrying bending load such as beam elements in floors.

I-joists—I-beams engineered from wood with fiberboard and/or laminated veneer lumber—are also becoming increasingly popular in construction, especially residential, as they are both lighter and less prone to warping than solid wooden joists. However, there has been some concern as to their rapid loss of strength in a fire if unprotected.

Design

I-beams are widely used in the construction industry and are available in a variety of standard sizes. Tables are available to allow easy selection of a suitable steel I-beam size for a given applied load. I-beams may be used both as beams and as columns.

I-beams may be used both on their own, or acting compositely with another material, typically concrete. Design may be governed by any of the following criteria:

- deflection: the stiffness of the I-beam will be chosen to minimize deformation

- vibration: the stiffness and mass are chosen to prevent unacceptable vibrations, particularly in settings sensitive to vibrations, such as offices and libraries

- bending failure by yielding: where the stress in the cross section exceeds the yield stress

- bending failure by lateral torsional buckling: where a flange in compression tends to buckle sideways or the entire cross-section buckles torsionally

- bending failure by local buckling: where the flange or web is so slender as to buckle locally

- local yield: caused by concentrated loads, such as at the beam's point of support

- shear failure: where the web fails. Slender webs will fail by buckling, rippling in a phenomenon termed tension field action, but shear failure is also resisted by the stiffness of the flanges

- buckling or yielding of components: for example, of stiffeners used to provide stability to the I-beam's web.

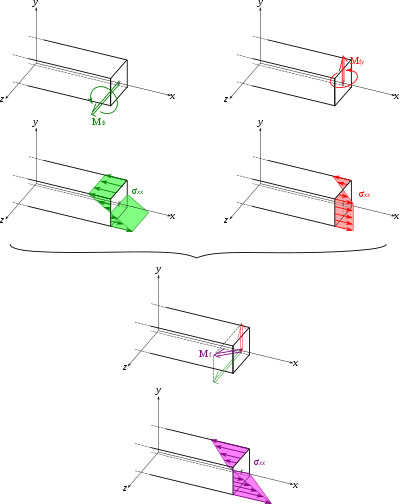

Design for bending

A beam under bending sees high stresses along the axial fibers that are farthest from the neutral axis. To prevent failure, most of the material in the beam must be located in these regions. Comparatively little material is needed in the area close to the neutral axis. This observation is the basis of the I-beam cross-section; the neutral axis runs along the center of the web which can be relatively thin and most of the material can be concentrated in the flanges.

The ideal beam is the one with the least cross-sectional area (and hence requiring the least material) needed to achieve a given section modulus. Since the section modulus depends on the value of the moment of inertia, an efficient beam must have most of its material located as far from the neutral axis as possible. The farther a given amount of material is from the neutral axis, the larger is the section modulus and hence a larger bending moment can be resisted.

When designing a symmetric I-beam to resist stresses due to bending the usual starting point is the required section modulus. If the allowable stress is and the maximum expected bending moment is , then the required section modulus is given by[3]

where is the moment of inertia of the beam cross-section and is the distance of the top of the beam from the neutral axis (see beam theory for more details).

For a beam of cross-sectional area and height , the ideal cross-section would have half the area at a distance above the cross-section and the other half at a distance below the cross-section.[3] For this cross-section

However, these ideal conditions can never be achieved because material is needed in the web for physical reasons, including to resist buckling. For wide-flange beams, the section modulus is approximately

which is superior to that achieved by rectangular beams and circular beams.

Issues

Though I-beams are excellent for unidirectional bending in a plane parallel to the web, they do not perform as well in bidirectional bending. These beams also show little resistance to twisting and undergo sectional warping under torsional loading. For torsion dominated problems, box beams and other types of stiff sections are used in preference to the I-beam.

Wide-flange steel materials and rolling processes (U.S.)

In the United States, the most commonly mentioned I-beam is the wide-flange (W) shape. These beams have flanges in which the planes are nearly parallel. Other I-beams include American Standard (designated S) shapes, in which flange surfaces are not parallel, and H-piles (designated HP), which are typically used as pile foundations. Wide-flange shapes are available in grade ASTM A992,[4] which has generally replaced the older ASTM grades A572 and A36. Ranges of yield strength:

- A36: 36,000 psi (250 MPa)

- A572: 42,000–60,000 psi (290–410 MPa), with 50,000 psi (340 MPa) the most common

- A588: Similar to A572

- A992: 50,000–65,000 psi (340–450 MPa)

Like most steel products, I-beams often contain some recycled content.

The American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC) publishes the Steel Construction Manual for designing structures of various shapes. It documents the common approaches, Allowable Strength Design (ASD) and Load and Resistance Factor Design (LRFD), (starting with 13th ed.) to create such designs.

Standards

The following standards define the shape and tolerances of I-beam steel sections:

Euronorms

- EN 10024, Hot rolled taper flange I sections – Tolerances on shape and dimensions.

- EN 10034, Structural steel I and H sections – Tolerances on shape and dimensions.

- EN 10162, Cold rolled steel sections – Technical delivery conditions – Dimensional and cross-sectional tolerances

Other

- DIN 1025-5

- ASTM A6, American Standard Beams

- BS 4-1

- IS 808 – Dimensions hot rolled steel beam, column, channel and angle sections

- AS/NZS 3679.1 – Australia and New Zealand standard[5]

Designation and terminology

- In the United States, steel I-beams are commonly specified using the depth and weight of the beam. For example, a "W10x22" beam is approximately 10 in (25 cm) in depth (nominal height of the I-beam from the outer face of one flange to the outer face of the other flange) and weighs 22 lb/ft (33 kg/m). Wide flange section beams often vary from their nominal depth. In the case of the W14 series, they may be as deep as 22.84 in (58.0 cm).[6]

- In Canada, steel I-beams are now commonly specified using the depth and weight of the beam in metric terms. For example, a "W250x33" beam is approximately 250 millimetres (9.8 in) in depth (height of the I-beam from the outer face of one flange to the outer face of the other flange) and weighs approximately 33 kg/m (67 lb/yd).[7] I-beams are still available in U.S. sizes from many Canadian manufacturers.

- In Mexico, steel I-beams are called IR and commonly specified using the depth and weight of the beam in metric terms. For example, a "IR250x33" beam is approximately 250 mm (9.8 in) in depth (height of the I-beam from the outer face of one flange to the outer face of the other flange) and weighs approximately 33 kg/m (22 lb/ft).[8]

- In India I-beams are designated as ISMB, ISJB, ISLB, ISWB. ISMB: Indian Standard Medium Weight Beam, ISJB: Indian Standard Junior Beams, ISLB: Indian Standard Light Weight Beams, and ISWB: Indian Standard Wide Flange Beams. Beams are designated as per respective abbreviated reference followed by the depth of section, such as for example "ISMB 450", where 450 is the depth of section in millimetres (mm). The dimensions of these beams are classified as per IS:808 (as per BIS).

- In the United Kingdom, these steel sections are commonly specified with a code consisting of the major dimension (usually the depth)-x-the minor dimension-x-the mass per metre-ending with the section type, all measurements being metric. Therefore, a 152x152x23UC would be a column section (UC = universal column) of approximately 152 mm (6.0 in) depth 152 mm width and weighing 23 kg/m (46 lb/yd) of length.[9]

- In Australia, these steel sections are commonly referred to as Universal Beams (UB) or Columns (UC). The designation for each is given as the approximate height of the beam, the type (beam or column) and then the unit metre rate (e.g., a 460UB67.1 is an approximately 460 mm (18.1 in) deep universal beam that weighs 67.1 kg/m (135 lb/yd)).[5]

American Standard Beams AISC

| Type | Beam height (in) | Flange width (in) | Web thickness (in) | Flange thickness (in) | Weight (lb/ft) | Cross-section area (in2) | Moment of inertia in torsion (J) (in4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W4x13 | 4.16 | 4.06 | 0.28 | 0.345 | 13 | 3.83 | 0.151 |

| W5x16 | 5.01 | 5 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 16 | 4.71 | 0.192 |

| W5x19 | 5.15 | 5.03 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 19 | 5.56 | 0.316 |

| W6x8.5 | 5.83 | 3.94 | 0.17 | 0.195 | 8.5 | 2.52 | 0.0333 |

| W6x9 | 5.9 | 3.94 | 0.17 | 0.215 | 9 | 2.68 | 0.0405 |

| W6x12 | 6.03 | 4 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 12 | 3.55 | 0.0903 |

| W6x15 | 5.99 | 5.99 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 15 | 4.43 | 0.101 |

| W6x16 | 6.28 | 4.03 | 0.26 | 0.405 | 16 | 4.74 | 0.223 |

Indian standard beams ISMB

| Type | Beam height (mm) | Flange width (mm) | Web thickness (mm) | Flange thickness (mm) | Weight (kg/m) | Cross-section area (cm2) | Moment of inertia in torsion (J) (cm4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISMB 80 | 80 | 46 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 7.64 | 0.7121 |

| ISMB 100 | 100 | 75 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 11.5 | 14.6 | 1.10 |

| ISMB 120 | 120 | 70 | 4.4 | 6.3 | 10.4 | 13.2 | 1.71 |

| ISMB 140 | 140 | 73 | 4.7 | 6.9 | 12.9 | 16.4 | 2.54 |

| ISMB 750 × 137 | 753 | 263 | 11.5 | 17 | 137 | 175 | 137.1 |

| ISMB 750 × 147 | 753 | 265 | 13.2 | 17 | 147 | 188 | 161.5 |

| ISMB 750 × 173 | 762 | 267 | 14.4 | 21.6 | 173 | 221 | 273.6 |

| ISMB 750 × 196 | 770 | 268 | 15.6 | 25.4 | 196 | 251 | 408.9 |

European wide flange beams HEA and HEB

| Type | Beam height (mm) | Flange width (mm) | Web thickness (mm) | Flange thickness (mm) | Weight (kg/m) | Cross-section area (cm2) | Moment of inertia in torsion (J) (cm4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HE 100 A | 96 | 100 | 5 | 8 | 16.7 | 21.2 | 5.24 |

| HE 120 A | 114 | 120 | 5 | 8 | 19.9 | 25.3 | 5.99 |

| HE 140 A | 133 | 140 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 24,7 | 31.4 | 8.13 |

| HE 160 A | 152 | 160 | 6 | 9 | 30.4 | 38.8 | 12.19 |

| HE 1000 × 415 | 1020 | 304 | 26 | 46 | 415 | 528.7 | 2714 |

| HE 1000 × 438 | 1026 | 305 | 26.9 | 49 | 437 | 557.2 | 3200 |

| HE 1000 × 494 | 1036 | 309 | 31 | 54 | 494 | 629.1 | 4433 |

| HE 1000 × 584 | 1056 | 314 | 35.6 | 64 | 584 |

Cellular beams

Cellular beams are the modern version of the traditional "castellated beam" which results in a beam approximately 40–60% deeper than its parent section. The exact finished depth, cell diameter and cell spacing are flexible. A cellular beam is up to 1.5 times stronger than its parent section and is therefore utilized to create efficient large span constructions.[10]

See also

- DIN 1025 – a DIN standard which defines the dimensions, masses and sectional properties of a set of I-beams

- I-joist

- Open web steel joist

- Reinforced concrete

- T-beam

- C-beam, also known as Structural channel or Parallel Flange Channel (PFC)

- Weld access hole

- Steel design

References

- Thomas Derdak, Jay P. Pederson (1999). International directory of company histories. 26. St. James Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-55862-385-9.

- The Morning Call (2003). "Forging America: The History of Bethlehem Steel". Morning Call Supplement. Allentown, PA, USA: The Morning Call. A detailed history of the company by journalists of the Morning Call staff.

- Gere and Timoshenko, 1997, Mechanics of Materials, PWS Publishing Company.

- "ASTM A992?A992M Standard Specification for Structural Steel Shapes". American Society for Testing and Materials. 2006. doi:10.1520/A0992_A0992M-06A.

- Hot rolled and structural steel products – Fifth edition Archived 2013-04-10 at the Wayback Machine — Onesteel. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- AISC Manual of Steel Construction 14th Edition

- Handbook of Steel Construction (9th ed.). Canadian Institute of Steel Construction. 2006. ISBN 978-0-88811-124-1.

- IMCA Manual of Steel Construction, 5th Edition.

- "Structural sections" (PDF). Corus Construction & Industrial. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-15.

- "Cellular Beams - Kloeckner Metals UK". kloecknermetalsuk.com. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

Further reading

- M. F. Ashby, 2005, Materials Selection in Mechanical Design, Elsevier. See chapters 8.4 - 8.5