Hungerford massacre

The Hungerford massacre was a series of random shootings in Hungerford, England on 19 August 1987, when Michael Robert Ryan, an unemployed antiques dealer and handyman, shot dead 16 people, including an unarmed police officer and his own mother, before shooting himself. The shootings, committed using a handgun and two semi-automatic rifles, occurred at several locations, including a school he had once attended. Fifteen other people were also shot but survived. No firm motive for the killings has ever been established, although one psychologist has theorised Ryan's motive for the massacre had been a form of "anger and contempt for the ordinary life" around him, which he himself was not a tangible part of.[2]

| Hungerford massacre | |

|---|---|

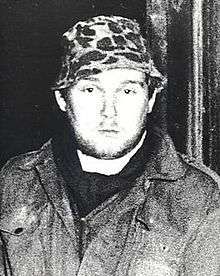

Michael Ryan in 1986[1] | |

| Location | Hungerford, Berkshire, England |

| Coordinates | 51.41°N 1.52°W |

| Date | 19 August 1987 c. 12:30 p.m. – c. 6:52 p.m. |

Attack type | Mass murder, spree shooting, murder-suicide, massacre, arson |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 17 (including the perpetrator) |

| Injured | 15+ |

| Perpetrator | Michael Robert Ryan |

| Motive | Inconclusive; mental illness suspected (acute schizophrenia and/or psychosis) |

A report on the massacre was commissioned by Home Secretary Douglas Hurd. The Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988 was passed in the wake of the incident, which bans the ownership of semi-automatic centre-fire rifles and restricts the use of shotguns with a capacity of more than three cartridges. The shootings remain one of the deadliest firearms incidents in British history.[3]

Perpetrator

Michael Robert Ryan was an unemployed labourer and antiques dealer. He was born at Savernake Hospital in Marlborough, Wiltshire, near Hungerford, Berkshire, on 18 May 1960.[4] His father, Alfred Henry Ryan (born 6 January 1905), was 55 years old when Michael was born. Alfred died in Swindon in May 1985 at the age of 80 from cancer. At the time of the shooting, Ryan lived with his mother, Dorothy (born 17 May 1924), a dinner lady at the local primary school. He had no siblings. There was extensive press comment on this, suggesting the relationship was "unhealthy" and that Ryan was "spoiled" by his mother. A Guardian headline described Ryan as a "mummy's boy". Ryan was a bachelor and had no children.

Ryan's true motives may never be known as he killed himself and his mother, the only other person who knew him well. Both John Hamilton (the medical director of Broadmoor Hospital[5]) and Jim Higgins (a consultant forensic psychiatrist for Mersey Regional Health Authority) thought he was schizophrenic and psychotic. Hamilton stated, "Ryan was most likely to be suffering from acute schizophrenia. He might have had a reason for doing what he did, but it was likely to be bizarre and peculiar to him."[6] The local vicar, David Salt, said on the first anniversary of the massacre, "No one has ever explained why Michael Ryan did what he did. And that's because, in my opinion, it is not something that can be explained."[6] Ryan's body was cremated at the Reading Crematorium on 3 September 1987, 15 days after the massacre.

Licensed firearms ownership

Ryan had been issued a shotgun certificate in 1978, and on 11 December 1986 he was granted a firearms certificate covering the ownership of two pistols. He later applied to have the certificate amended to cover a third pistol, as he intended to sell one of the two he had acquired since the granting of the certificate (a Smith & Wesson .38-caliber revolver) and to buy two more. This was approved on 30 April 1987. On 14 July, he applied for another variation, to cover two semi-automatic rifles, which was approved on 30 July. At the time of the massacre, he was in licensed possession of the following weapons:

- Zabala shotgun

- Browning shotgun

- Beretta 92FS semi-automatic 9 mm pistol

- CZ ORSO semi-automatic .32-calibre pistol

- Bernardelli .22-calibre pistol

- Norinco Type 56S 7.62×39mm semi-automatic rifle[7]

- M1 carbine .30 (7.62×33mm) semi-automatic rifle (a rare "Underwood" model)

Ryan used the Beretta pistol, and the Type 56 and M1 rifles, in the massacre. The CZ pistol was being repaired by a dealer at the time.[8] The Type 56 was purchased from firearms dealer Mick Ranger.[9]

Shootings

Savernake Forest

The first shooting occurred seven miles (11 km) to the west of Hungerford in Savernake Forest in Wiltshire, at 12:30 in the afternoon of 19 August. Susan Godfrey, 35, had come to the area with her two children, Hannah (4) and James (2), from Reading for a family picnic. Ryan approached them with his gun raised and forced Susan to place the children in her Nissan Micra. He then marched her into bushes at gunpoint and shot her 13 times in the back, using the whole magazine of the Beretta pistol. Police were alerted to the scene after Godfrey's two children approached a lone pensioner, Myra Rose. Hannah told Rose that a "man in black has shot our mummy."[10] Authorities were still responding when Ryan continued his massacre.[11]

A4 petrol station

Ryan drove his silver Vauxhall Astra GTE from the forest along the A4 towards Hungerford, and stopped at the Golden Arrow petrol station just outside the village of Froxfield, three miles (5 km) from the town.[12] After waiting for a motorcyclist, Ian George, to depart from the garage, he began to pump petrol into his car before shooting at the female cashier, Kakaub Dean, missing her. Ryan entered the store and again tried to shoot her at close range with his M1 carbine,[8] but the rifle's magazine had fallen out, probably because he inadvertently hit the release mechanism. He then left and continued towards Hungerford. Meanwhile, George, having witnessed the attempted shooting of Dean, stopped in Froxfield and placed the first emergency call to the police, reporting that he had seen an attempted armed robbery.

Hungerford

South View and Fairview Road

At around 12:45, Ryan was seen at his home in South View, Hungerford. He loaded his car with his weapons and attempted to drive away, but the car would not start. He then fired four shots into the right side of the car. Neighbours reported seeing him agitatedly moving between the house and the car before he returned indoors and shot and killed the family dog or dogs (accounts disagree on whether there were one or two dogs in the house). Ryan then doused his home with the petrol he had bought earlier in the day and set his house alight. The fire subsequently destroyed three adjoining properties.[13] Ryan then removed the three guns from the boot of his car and shot and killed Roland and Sheila Mason, who were in the back garden of their house: Roland was shot six times and Sheila once in the head.[6]

Ryan walked towards the town's common, critically injuring two more people; Marjorie Jackson was shot once in the lower back as she watched Ryan from the window of her living room and 14-year-old Lisa Mildenhall four times in both legs and abdomen as she stood outside her home. Mildenhall later recalled that Ryan smiled at her before crouching and shooting. Mildenhall was treated in a nearby home and survived.[14] Meanwhile, Jackson pulled 77-year-old Dorothy Smith into her home as she rebuked Ryan for making noise. Jackson first called 999 before telephoning George White, a colleague of her husband Ivor Jackson. She informed White that she had been injured. Her husband insisted on returning home and White offered to drive him. Jackson survived; Smith was uninjured.[15]

On the footpath towards the common, Ryan encountered a family walking their dog.[16] Upon seeing Ryan with his weapons, 51-year-old Kenneth Clements raised his arms in a gesture of surrender, diverting Ryan's attention as Clement's family climbed over a wall and ran to safety. Ryan ignored the gesture and shot Clements once at close range in the chest, killing him instantly. He fell to the ground still clutching the lead of his dog.[1] Looping back to South View, Ryan fired 23 rounds at PC Roger Brereton, a police officer who had just arrived at the scene in response to reports of gunfire. Brereton was hit four times in his chest:[17] his Vauxhall Senator veered and crashed into a telephone pole. He died sitting in his patrol car, radioing to his colleagues that he had been shot.[18] Ryan next turned his weapons on Linda Chapman and her teenage daughter, Alison, who had turned onto South View moments after Brereton was shot. Ryan fired 11 rounds from his semi-automatic into their Volvo 360; the bullets travelled through the bonnet of the car, hitting and critically wounding Alison in her right thigh. Ryan also shot through the windscreen, hitting Linda with glass and a bullet in the left shoulder. As Ryan reloaded his weapons, Linda reversed, exited South View and drove to the local doctor. A bullet was subsequently found lodged at the base of Alison's spine; during an operation to remove it, surgeons decided that the risk of paralysis was too great, and the bullet was left in place.[19]

After the Chapmans had driven away from South View, George White's Toyota Crown drove towards Ryan; Ivor Jackson was in the passenger seat. Ryan opened fire with his Type 56, killing White with a single shot to the head and leaving Jackson severely injured in his head and chest. White's Toyota crashed into the rear of Brereton's police car. Jackson played dead and hoped that Ryan would not move in for a closer look.[20]

Ryan moved along Fairview Road, killing Abdul Rahman Khan while he was mowing his lawn. Further along the road he wounded his next door neighbour, Alan Lepetit, who had helped build Ryan's gun display unit. He then shot at an ambulance which had just arrived, shattering the window and injuring paramedic Hazel Haslett, who sped away before Ryan was able to fire at her and her colleague again.[16]

Ryan shot at windows and at people who appeared on the street. Ryan's mother, Dorothy, then drove into South View and was confronted by her burning house, her armed son, and the dead and injured strewn along the street.[21] Ivor Jackson, who was still slumped in White's Toyota, heard Dorothy open the door of the car and say, "Oh, Ivor..." before attempting in vain to reason with her son.[17] Ryan shot her in her abdomen and legs before firing two fatal shots into her back as she lay on the ground.[21] Ryan then wounded Betty Tolladay, who had stepped out of her house to admonish Ryan for making noise, as she had assumed he was shooting at paper targets in the woods.[22] Ryan then ran towards Hungerford Common.

The police were now informed of the situation but the evacuation plan was not fully effective. Ryan's movements were tracked via police helicopter almost an hour after he set his home alight, but this was hampered by media helicopters and journalists responding to reports of the attacks. A single police officer, who observed Ryan, recommended that armed police be used, as the weapons he saw in Ryan's possession were beyond the capabilities of Hungerford police station's meagre firearms locker.[23]

Hungerford Common and town centre

On Hungerford Common, Ryan went on to shoot and kill young father-of-two, Francis Butler, as he walked his dog, and shot at, but missed, teenager Andrew Cadle, who sped away on his bicycle.[1] Local taxi driver Marcus Barnard slowed down his Peugeot 309 as Ryan crossed in front of him. Ryan shot him with the Type 56, causing a massive injury to his head and killing him. Barnard had been redirected towards the Common by a police diversion as communication between ground forces and the police helicopter remained sporadic. Ann Honeybone was slightly injured by a bullet as she drove down Priory Avenue. Ryan then shot at John Storms, a washing-machine repairman who had parked on Priory Avenue.[24] Hit in the face, Storms crouched below the dashboard of his Renault Express.[25] He heard Ryan fire twice more at his van and felt the vehicle shake, but he was not hit again. A local builder named Bob Barclay ran from his nearby house and dragged Storms out of his van and into the safety of his home.[26]

Ryan then walked towards the town centre of Hungerford, where police were attempting to evacuate the public. During this, Ryan killed 67-year-old Douglas Wainwright and injured his wife Kathleen in their car. Kathleen would later say that her husband hit the brakes as soon as the windscreen shattered. Ryan fired eight rounds into the Wainwrights' Datsun Bluebird,[10] hitting Douglas in the head and Kathleen in the chest and shoulder. Kathleen, seeing that her husband was dead and that Ryan was approaching the car whilst reloading, unbuckled her seatbelt and ran.[1] The pair were visiting their son, a policeman on the Hungerford force. Coincidentally, Constable Wainwright had signed Ryan's request to extend his firearm certificate only weeks earlier. Next was Kevin Lance, who was shot in the upper arm[27] as he drove his Ford Transit along Tarrant's Hill.[26]

Further up Priory Avenue, a 51-year-old handyman named Eric Vardy[28] and his passenger, Steven Ball, drove into Ryan's path while travelling to a job in Vardy's Leyland Sherpa. Ball later recalled that he saw Lance clutching his arm and running into a narrow side street. As Ball focused on Lance, Ryan shattered the windscreen with a burst of bullets. Vardy was hit twice in the head and upper torso[13] and crashed his van into a wall; he would later die of shock and haemorrhage from his neck wound. Ball suffered no serious injuries.[1]

Throughout his movements, Ryan had also opened fire on a number of other people, some of whom were grazed or walking wounded. Many of these minor casualties were not counted in the eventual total.

At around 13:30,[27] Ryan crossed Orchard Park Close into Priory Road, firing a single round at a passing red Renault 5. This shot killed the driver, 22-year-old Sandra Hill.[29] A passing soldier, Carl Harries, rushed to Hill's car and attempted in vain to apply first aid, but Hill died in his arms.[30]

After shooting Hill, Ryan shot his way into a house further down Priory Road and killed the occupants. Jack Gibbs was killed instantly as he attempted to shield his wheelchair-bound wife, Myrtle, from Ryan with his own body. Myrtle died of her injuries two days later. Ryan also fired shots into neighbouring houses from the Gibbses' house, injuring Michael Jennings at 62 Priory Road and Myra Geater at 71 Priory Road.[1] Ryan continued down Priory Road where he encountered 34-year-old Ian Playle, who was returning from a shopping trip with his wife and two young children in their Ford Sierra. Playle crashed into a stationary car after being shot in the neck by Ryan. His wife and children were unhurt. Harries again rushed over to administer first aid, but Playle's wound proved to be fatal[1] as he died in an Oxford hospital two days later.[31]

Suicide

After shooting and injuring 66-year-old George Noon in his garden, Ryan broke into the John O'Gaunt Community Technology College, where he had formerly been a pupil. The school was closed and empty for the summer holidays. Ryan barricaded himself in a classroom. Police surrounded the building and found a number of ground-staff and two children who had seen Ryan enter. They offered guidance to the police on how to enter, and of hiding places. Ryan shot at circling helicopters and waved what appeared to be an unpinned grenade through the window, though reports differ whether Ryan actually possessed a grenade. Police attempted negotiations to coax Ryan out of the school, but these attempts failed. He refused to leave before knowing what had happened to his mother, saying that her death was "a mistake". At 18:52, Ryan shot himself in the head with the Beretta pistol.[32]

One of the statements Ryan made towards the end of the negotiations was widely reported: "Hungerford must be a bit of a mess. I wish I had stayed in bed."[33]

Murdered victims

The dead were:

- Susan Godfrey – mother with children – shot at Savernake Forest

- Roland Mason – neighbour – shot on South View

- Sheila Mason – neighbour – shot on South View

- Kenneth Clements – father walking with his family – shot on Hungerford Common

- Roger Brereton – unarmed police officer – shot on South View

- George White – driver – shot on South View

- Abdul Rahman Khan – neighbour – shot on South View

- Dorothy Ryan – Ryan's mother – shot on South View

- Francis Butler – father walking his dog – shot in Memorial Gardens

- Marcus Barnard – taxi driver – shot on Bulpit Lane

- Douglas Wainwright – police officer's father – shot on Priory Avenue

- Eric Vardy – van driver – shot on Tarrants Hill

- Sandra Hill – driver – shot on Priory Road

- Victor Gibbs – occupant of a house Ryan invaded – shot on Priory Road

- Myrtle Gibbs – occupant of a house Ryan invaded – shot on Priory Road

- Ian Playle – driver with family – shot on Priory Road

Police response

Hungerford was policed by two sergeants and twelve constables, and on the morning of 19 August 1987 the duty cover for the section consisted of one sergeant, two patrol constables and one station duty officer.[34] A number of factors hampered the police response:[18]

- The telephone exchange could not handle the number of 999 calls made by witnesses.

- The Thames Valley firearms squad were training 40 miles (64 km) away.

- The police helicopter was in for repair, though it was eventually deployed.

- Only two phone lines were in operation at the local police station, which was undergoing renovation.

Official report

The Hungerford Report was commissioned by Home Secretary Douglas Hurd from the Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police, Colin Smith. Ryan's collection of weapons had been legally licensed, according to the Report. The Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988[35], which was passed in the wake of the massacre, bans the ownership of semi-automatic centre-fire rifles and restricts the use of shotguns with a capacity of more than three cartridges (in magazine plus the breech).

Notoriety

The Hungerford massacre remains, along with the 1996 Dunblane school massacre, and the 2010 Cumbria shootings, one of the worst criminal atrocities involving firearms to occur in the United Kingdom. The Dunblane and Cumbria shootings had a similar number of fatalities, and in both cases the perpetrators killed themselves. Only one person died in the 1989 Monkseaton shootings, but 14 others were wounded, and the perpetrator did not kill himself.

In the days following the massacre, the British tabloid press was filled with stories about Ryan's life. Press biographies all stated that he had a near-obsessive fascination with firearms. The majority claimed that Ryan had possessed magazines about survival skills and firearms, Soldier of Fortune[36] being frequently named.

Cultural references

In literature

- J. G. Ballard's novel, Running Wild, centres on the fictitious Richard Greville, a Deputy Psychiatric Advisor with the Metropolitan Police Service who authored "an unpopular minority report on the Hungerford killings" and is sent to investigate mass murder in a gated community.[37] Ballard professed an interest in the Hungerford massacre and other "pointless crimes" such as that in Dunblane and the murder of Jill Dando.

- The Hungerford massacre inspired Christopher Priest's novel The Extremes (1998).[38]

In music

In television

- In September 2003, the BBC's third series of Waking the Dead featured a storyline in the episode "Multi-story" which closely resembled the events of the Hungerford massacre. The episode focuses on an unemployed and socially awkward man named Carl McKenzie who has been convicted of opening fire on a town centre crowd from a multi-storey car park, and killing a number of people including his own parents and a police officer.

See also

- Hoddle Street massacre

- List of massacres in Great Britain

- List of rampage killers

- Port Arthur massacre (Australia), a similar spree killing in Tasmania (Australia), that took place 9 years after the Hungerford massacre, which prompted similar gun law reforms

- Southcliffe

- Ughill Hall shootings, which occurred eleven months earlier in Sheffield

References

- "Hungerford Massacre". Jeremyjosephs.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- "Death in the Afternoon". 8 December 2004. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "BBC: On this Day". 19 August 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Jeremy Josephs. Hungerford – One Man's Massacre. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "OBITUARY: J R Hamilton". British Medical Journal. 301: 116. 14 July 1990. doi:10.1136/bmj.301.6743.116. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Hungerford Massacre". 4 January 2006. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006.

- Chinese copy of the Russian Kalashnikov AK-47.

- The Hungerford Report – Shooting Incidents At Hungerford On 19 August 1987, Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police Colin Smith to Home Secretary Douglas Hurd. Retrieved 24 August 2007. Archived 22 January 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Barnett, Antony (27 April 2003). "Exposed: Global dealer in death". The Guardian. London.

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 169

- Courtroom Television Network (2005). Michael Ryan – The Hungerford UK Mass Murderer Archived 4 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 October 2005.

- Marshall, Brian Robert (2010). Golden Arrow Service Station, Froxfield, Marlborough (3), Geograph, Accessed 24 May 2017.

- "The Crimes – Michael Ryan and the Hungerford Massacre on Crime and Investigation Network". Crimeandinvestigation.co.uk. 19 August 1987. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Parry, Gareth (20 August 1987). "Gunman in combat gear kills himself after 14 die in shooting spree". The Guardian. London.

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 12

- Mass Murderers, p. 172 ISBN 0-7835-0004-1

- "Michael Ryan, the Hungerford UK Mass Murderer – Whatever Moves – Crime Library on". Trutv.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Grice, Elizabeth (7 December 2004). "Ryan shot at me, then at my mother". London: The Telegraph.

- How I Survived the Hungerford Massacre – Sky The Magazine – August 2007

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 173

- "Michael Ryan, the Hungerford UK Mass Murderer – Ryans Rampage – Crime Library on". Trutv.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 174

- Mass Murderers, p. 173 ISBN 0-7835-0004-1

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 178

- "HUNGERFORD MASSACRE ANNIVERSARY". www.itnsource.com.

- "Hungerford Report Ryan Police August Pistol 1987 Station". Economicexpert.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 179

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 179–180

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 180

- Courtenay-Smith, Natasha (10 August 2007). "Haunted by Hungerford". Daily Mail. London.

- "The Glasgow Herald – Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 184

- Michael Ryan – The Hungerford UK Mass Murderer Archived 29 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 October 2005.

- The Hungerford Report – Shooting Incidents At Hungerford On 19 August 1987, Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police Colin Smith to Home Secretary Douglas Hurd Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988 (c. 45). Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- – Errol Mason (1993). "Critical Factors in Firearms Control" (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. p. 209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2005.

- – Cultural Studies, edited by Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, Paula Treichler (1991), p220. Google Print. ISBN 0-415-90345-9 (accessed 28 October 2005). Also available in print from Routledge (UK).

- Charles Platt (2017). Dream Makers. Orion. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-4732-1968-7.

- – Mac Randall (1 September 2004). Exit Music: The Radiohead Story, 119. Google Print. ISBN 1-84449-183-8 (accessed 28 October 2005). Also available in print from Omnibus Press.

- "If You'd Rather Be Playing Golf......or Rugby: December 2004".

Sources

- Josephs, Jeremy (21 February 2013). The Hungerford Massacre (Kindle ed.). Simba Books. ASIN B00BJP4UQA.

- M. Barker and J. Petley (eds) (26 April 2001). Ill Effects: The Media Violence Debate (Communication & Society. Routledge; 2Rev Ed editio. pp. 63–77. ISBN 0-415-22513-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Webster, Duncan (May 1989). "Whodunnit? America did: Rambo and post-Hungerford rhetoric". Cultural Studies. Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group. 3 (2): 173. doi:10.1080/09502388900490121.