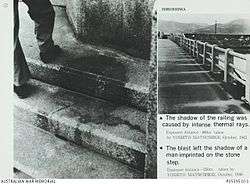

Human Shadow Etched in Stone

Human Shadow Etched in Stone (Japanese: 人影の石 hitokage no ishi)[2] is an exhibition at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. It is thought to be the residue of a person who was sitting at the entrance of Hiroshima Branch of Sumitomo Bank when the atomic bomb was dropped over Hiroshima. It is also known as Human Shadow of Death.[1]

Background

According to the museum, it is thought that the person had been sitting on the stone step waiting for the bank to open when the heat from the bomb burned the surrounding stone white and left their shadow.[3][4] A black deposit was also found on the shadow.[5] A piece of stone containing the artifact (3.3 meters wide by 2 meters high) was cut from the original location and moved to the museum.[6]

In January 1971, the museum acquired the stone on which the human shadow had become indistinct due to weathering. In April 1975, the museum began research into preserving the shadow.[7] In 1991, the museum reported that earnest investigation of preservation methods had commenced.[8] At present, the stone is surrounded by glass.[9][10]

It is thought that the person depicted in the stone died immediately with the flash of the atomic bomb, or after falling down after the explosion.[3][11] Some people stated that they saw the person sitting at the entrance just before the bombing.[12] A former soldier testified that he had recovered the person's body. However, the person's identity is still unknown.[12] As of 2016, the museum exhibit states that "Several people have suggested that the person could be a member of their family". In the past, the museum exhibit contained a statement that the person was a 42-year-old woman named Mitsuno Koshitomo (越智ミツノ).[12] As a result of these previous statements, some conclusions in the literature state that she was the person depicted in the stone.

According to museum staff, many visitors to the museum believe that the shadow is the outline of a human vaporized immediately after the bombing.[4] However, the possibility of human vaporization is not supported from a medical perspective. The ground surface temperature is thought to have ranged from 3,000 to 4,000 degrees Celsius just after the bombing. Exposing a body to this level of radiant heat would leave bones and carbonized organs behind. While radiation could severely inflame and ulcerate the skin, complete vaporization of the body is impossible.[4]

History

Hiroshima Branch of Sumitomo Bank

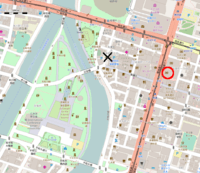

The black x-mark indicates ground zero, while the red circle is the Hiroshima Branch of Sumitomo Bank (now Sumitomo Mitsui Bank)

The black x-mark indicates ground zero, while the red circle is the Hiroshima Branch of Sumitomo Bank (now Sumitomo Mitsui Bank) Aerial photograph on July 25, 1945, before the bombing

Aerial photograph on July 25, 1945, before the bombing Aerial photograph on August 8, 1945, two days after the bombing

Aerial photograph on August 8, 1945, two days after the bombing

Human Shadow Etched in Stone was originally part of the stone steps at the entrance of the Hiroshima Branch of Sumitomo Bank, located 260 meters from ground zero.[1][3] The current location of the Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, Hiroshima Branch is Kamiya-cho 1 Chome.[lower-alpha 1]

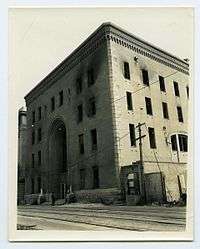

The bank was built in 1928. It was designed by Kenzo Takekoshi (竹腰健造) at the department of engineering of Sumitomo Group (now Nikken Sekkei), and was constructed by the Obayashi Corporation.[14] The building was constructed out of reinforced concrete, with four floors above ground and one below with an open ceiling up to the third floor. The rooms for business, reception and coinage were on the first floor, the meeting rooms and cafeteria on the fourth floor, and the boiler room in the basement.[14][15] It was built south of the head office of Geibi Bank (Now head office of Hiroshima Bank,) which had been built the year before and was almost the same size. It was designed in a general Romanesque architectural style, and was characterized by a large arch with molding on its front facade.[14]

It was not totally destroyed in the bombing of August 6, 1945. While the interior was destroyed, the exterior remained.[15] The coin room was not damaged, and the cash and passbooks remained.[15] Papers inside the building were blown as far away as Numata-cho by the blast.[lower-alpha 2][15]

On the morning of the bombing, the bank was to be open as usual. Most of the employees were on their way to the office when the bomb was dropped. There were 29 employees killed immediately (including those in the branch and those on their way to work), 40 were injured and none missing.[15] Some of the survivors died within a few days from radiation sickness, while others worked until retirement.[15] Passersby took refuge in the building as it was close to ground zero, and a large number of bodies were recovered.[15]

The branch reopened after the war, and the entrance soon became a famous landmark of the damage caused by the atomic bombing. It was officially recognized by Hiroshima City as an A-bomb site.[17] In those days, the shadow was called "Human Shadow of Death".[1][18] According to a testimony, it was the second most famous sight next to the Atomic Bomb Dome.[19] Sumitomo Bank went to great lengths to preserve the shadow. In 1959 they built a fence surrounding the stone, and in 1967 they covered the stone with tempered glass to prevent deterioration.[1][6][18]

In 1971, the Hiroshima Branch was planned to be rebuilt. The stone around the shadow was cut out and donated to the museum.[1][6]

Human vaporization

According to Masaharu Hoshi (1947–), a radiology scientist, in his childhood he heard that the shadow had been generated by "human vaporization".[4] "Journal on the damage of atomic bombing in Hiroshima" (広島原爆戦災誌), published by Hiroshima City in 1971, also contains a description implying human vaporization, which is now proven to be impossible.[4]

Within a radius of 500 meters of the ground zero, (Omitted) people were killed almost immediately as if they had been vaporized … bodies and bones were burned thoroughly almost not to be found, and everything was destroyed, which was buried in white ash.

— Hiroshima City, Journal on the damage of atomic bombing in Hiroshima vol.2[20] (translation mine)

In the 1994 Committee on Health and Welfare of the House of Councillors, Eimatsu Takakuwa mentioned the stone, saying "One was vaporized and vanished immediately. Only the shadow remained."[21]

Notes

References

- "ヒロシマの記録 貴重な「記憶」次代へ" (in Japanese). Chugoku Shimbun. 2004-03-22. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "Human Shadow Etched in Stone". Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "人影の石" (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "熱線で「人が蒸発」本当?" (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Media Center. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "ヒロシマの記録2000 3月" (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Media Center. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "ヒロシマの記録1971 1月" (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Media Center. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "ヒロシマの記録1975 4月" (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Media Center. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "ヒロシマの記録1991 5月" (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Media Center. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "針折れる 広島資料館の収蔵資料約2万点、劣化進む". Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). 2015-12-12. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- "オバマ大統領広島訪問直前に巻き起こった原爆資料館批判" (in Japanese). News Post Seven. 2016-05-25. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "人影の石" (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "「人影の石」説明板に名前追加" (in Japanese). Chugoku Shimbun. 1997-08-02. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- A-bombed Buildings Investigation Committee (1996). ヒロシマの被爆建造物は語る (in Japanese). Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. p. 44.

- Li, MING; ISHIMARU, Norioki (2006). "The Study on the Activities and Their Features of Architects in Hiroshima Before World War Two: The study on the architects activity form and feature in local city". Journal of Architecture. Architectural Institute of Japan. 71 (608): 197–204. doi:10.3130/aija.71.197_4. ISSN 1340-4210.

- Hiroshima City (2005) [1971]. 広島原爆戦災誌 (PDF) (in Japanese). 3. Hiroshima City. pp. 149–152. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "地理院地図" (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

- "ヒロシマの記録 消えた「原爆十景」追う" (in Japanese). Chugoku Shimbun. 2007-04-30. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "1945年8月~被爆した広島、長崎~ 写真特集". Jiji Press. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "巻頭言:被爆建物の記憶" (in Japanese). DDK Cooperative (協同組合DDK). 2013. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- Hiroshima City (2005) [1971]. 広島原爆戦災誌 (PDF) (in Japanese). 2. Hiroshima City. p. 5. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- "参議院会議録情報 第131回国会 厚生委員会 第11号". Full-text Database System for the Minutes of the Diet (in Japanese). National Diet Library. Retrieved 2017-09-22.