Hugh III of Maine

Hugh III (c. 960 – c. 1015) became Count of Maine on his father Hugh II's death, c. 991.

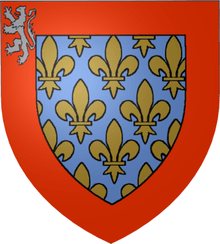

Hugh III count of Maine | |

|---|---|

Arms of the Counts of Maine (modern depiction) | |

| Born | c. 960 |

| Died | c. 1015 |

| Noble family | Hugonide Carolingian |

| Father | Hugh II, Count of Maine |

Life

He was the son of Hugh II, Count of Maine and succeeded his father as Count of Maine c. 991[1] He constructed the fortress at Sablé[2] but by 1015 it ended up being held by the viscounts of Maine.[3] He was a supporter of Richard II, Duke of Normandy.[lower-alpha 1][4] Allied with Odo II, Count of Blois, he fought against the kings Hugh Capet and Robert II of France, but he was forced to acknowledge the Count of Anjou as his suzerain. During the siege of Tillières, Hugh narrowly escaped from the Norman forces pursuing him by disguising himself as a local shepherd.[5] Throughout the tenth century the dynasty of counts of Maine, of which Hugh III, his father Hugh II, and grandfather Hugh I were all members struggled to control both the city of Le Mans and church investitures[6] and in that effort were in near constant warfare with the Bishops of Le Mans, notably Segenfridus and Avesgaudus.[7] Between 995 and 1015 Hugh III donated several properties including four vineyards and three mills in Le Mans to the monks of Mont Saint-Michel In Normandy.[8] When approached by Abbot Hildebert in 1014 in requesting more land in the area of Le Mans, Hugh III generously gave the land of Voivres and personally placed the offering on the altar at Mont Saint-Michel.[8] Hugh died c. 1014–1015.[1]

.svg.png)

Issue

While the name of his wife is not known it is very probable she was a sister of Judith of Rennes wife of Richard II, Duke of Normandy.[9] Their son was:

- Herbert I, Count of Maine[1] who succeeded him.

References

- Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band III Teilband 4 (Verlag von J. A. Stargardt, Marburg, Germany, 1989), Tafel 692

- W.Scott Jessee, Robert the Burgundian and the Counts of Anjou, ca. 1025-1098 (Catholic University of America Press, 2000), p. 44

- Richard E. Barton, Lordship in the County of Maine, c. 890-1160 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2004), p. 122

- Francis Palgrave, The History of Normandy and of England (London: J.W. Parker & Son, 1864), pp. 123, 125

- The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumieges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Vol. II, Books V-VIII, ed. Elisabeth M.C. Van Houts (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1995), pp. 24-5

- Richard E. Barton, Lordship in the County of Maine, c. 890-1160 (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2004), p. 52

- Richard E. Barton, Lordship in the County of Maine, c. 890-1160 (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2004), p. 148

- Cassandra Potts, Monastic Revival and Regional Identity in Early Normandy(The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1997), pp. 93-4

- K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, Poppa of Bayeux And Her Family, The American Genealogist, Vol. 72 No.4, (July/October 1997), p. 194 & n. 26

Notes

- K.S.B. Keats-Rohan believes they were brothers-in-law, see: K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, Poppa of Bayeux And Her Family, The American Genealogist, Vol. 72 No.4, (July/October 1997), p. 194 & n. 26

| Preceded by Hugh II |

Count of Maine c.991–c.1014 |

Succeeded by Herbert I |