Hugh Gemmell Lamb-Smith

Hugh Gemmell Lamb-Smith (31 March 1889 – 26 December 1951), known as Gemmell, was an innovative Australian educator who landed at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, on Sunday, 25 April 1915 as a member of the Second Field Ambulance unit, and went on to serve in Europe for the duration of the war. He also served (immediately post-war) as an AIF Education Scheme Instructor in Belgium. He was a prominent (lay) member of the Melbourne Anglican community, and he taught at Caulfield Grammar School from 1913 to 1951.[2]

- "He was a man of wide and sympathetic culture. In addition to his love for music, he was a discriminating connoisseur of painting, and a devotee of ballet and the theatre. He was a devoted churchman and interested in manly sports. Above all, he was an idealist, but, unlike many idealists, he was ready to give practical expression to his ideals." — Webber (1981), p.248

active service, so get just the 1lb. of meat, ½lb. of bread, and ½lb.

biscuits (heavens, no wonder they are strict about teeth), and sundry

things, like salt, vegetables tea, &c.

We also carry two days' rations in little bags, which we sling on

our overcrowded persons; they are very cute affairs, and contain

tinned meat, biscuits, tin of soup powders, tea, and sugar.

To give you an idea of what army ambulance corps have to carry

I will make a list:– Belt, in which is first aid pouch and mess tin, own

waterbottle, own haversack in which are housewife,[4] towel, and little

things; iron rations, overcoat rolled to contain Balaclava, muffler,

spare socks, waterproof, blanket, and change of garments in a roll;

patients' waterbottle, and haversack of medical comfort.

Still, we can do it, so the training does something, you see. …

It is marvelous how the wounded stand being dragged by us over

all kinds of ghastly places.

The first day I think I bandaged everything from a shot-off finger

to a broken back.

We have all got little humpies dug out of the hill for safety, and at

present it is more like a foreshore camp of the "Gayboys" than a war.[5]

The weather is superb, not a cloud, but the nights are quite cold.

Gemmell Lamb-Smith | |

|---|---|

_-_in_1930.jpg) H.G. Lamb-Smith at C.G.S. (1930) | |

| Born | 31 March 1889 |

| Died | December 26, 1951 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Education | |

| Occupation |

Wangaratta Grammar School

|

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Vernon Lamb-Smith (née Harris) |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Signature | |

Family

The son of William and Margaret Serpine "Maggie" Lamb-Smith, née Gemmell, Hugh Gemmell Lamb-Smith was born on 31 March 1889, at Cheltenham, Victoria.[6] and died on 26 December 1951, at his home in East St Kilda, Victoria.[7]

Father and mother

His father, William Lamb-Smith (1846–1910), born in Renfrewshire, Scotland in 1846, was a Justice of the Peace, and a prominent auctioneer and land developer in the outskirts of Melbourne.[8] He was also, among many things: a Councillor of the Moorabbin Shire Council from 1899 until 1902 (when, due to his move from Beaumaris to Armadale, he was no longer residentially qualified to serve), and served as its President in 1893;[9][10] President of the Cheltenham Lawn Tennis Club;[11] President of the Mentone Erica Literary, Musical and Dramatic Society,[12] the Captain of the Cheltenham Rifle Club from its inception until his death (in Armadale, Victoria on 23 May 1910);[13] and the Consul-General for Paraguay.[14]

His mother, Margaret Serpine "Maggie" Lamb-Smith (1853–1938), née Gemmell — who had married William in St Kilda, Victoria on 19 April 1883[15] — was the daughter of Hugh Mitchell Campbell Gemmell (1827–1880), and Simonette Marie Gemmell, née Christiani (1824–1888). Born in the West Indies,[16] she "was much given to good works, and rated serving people more highly than reputation or wealth", and, moreover, "was sensitive to the beauties represented by art, and especially music".[17] She was a life governor of the Alfred Hospital, and a member of the foundation committee of the Convalescent Home for Men, at Cheltenham (which operated from 1886 to 1956). She died at St Kilda on 22 June 1938.[18]

Sister

Gemmell's only sibling, Mora Marie Lamb-Smith (1884–1945),[19] was a trained nurse.[20] She enlisted in World War I, and served in India, with the rank of Sister, in the Australian Army Nursing Service.[21] She returned to Australian on 17 May 1919, and her military appointment was terminated on 29 June 1919.[22] She married Hugh Gibson Gemmell Sloane (1875–1960), of Mulwala, New South Wales on 26 October 1921 at Christ Church in South Yarra;[23][24] they had two sons, one of whom died at the age of seven. Mora and her brother Gemmell were both confirmed at the same ceremony at Saint George's Anglican Church in Malvern, Victoria on 21 June 1904.[25]

Wife

One of the five daughters and four sons of William Marshall Harris, (1842–1905), bank manager, and Alderman of the Borough of Armidale, and Marina Jane Harris (1851–1914), née Ross,[26] Dorothy Vernon Harris (1885–1964) was born in Armidale on 3 September 1885.[27] One of her brothers, Second Lieutenant Philip Vernon Harris, A.I.F. (1880–1917), died of wounds on 11 June 1917, in France.[28]

Dorothy graduated from the Sydney Kindergarten Training College as a fully qualified kindergarten teacher in December 1908.[29] She married Gemmell Lamb-Smith at Turramurra (a suburb of Sydney), on 17 May 1924.[30] They had no children. Dorothy died in Sydney on 15 August 1964.[31]

From his own, direct, personal experience of Dorothy, Horace Webber (1981, p. 248), observed that she was a "gracious lady", and remarked that she was well aware of the sufferings Gemmell experienced as an ever-present consequence of the horrors of his wartime experiences, and that, once they were married, "her benign influence did much to restore his peace of mind" — and there's no doubt that Dorothy's innate, natural propensities in these directions had been considerably enhanced by her own extensive wartime experiences of working for the Red Cross, as a quartermaster, in Australian military hospitals in England from 1916 to 1919.[32][33][34]

She was one of the 2,300 Victorians that were awarded a Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal in June 1953.[35]

Education

He was educated at Scotch College, Melbourne from 1901 to 1904,[36][37] at various other schools, and, then, at Wangaratta Grammar School (in 1907),[38] where he not only completed his Junior Public Examination studies,[39] but was also (concurrently) employed as a teacher.[40] In 1910, he enrolled as an "evening student" in a Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Melbourne).[41]

In addition to the extra-curricular studies he had pursued in England under the auspices of the AIF Education Scheme prior to his return to Australia in November 1919, he resumed his "evening student" university studies in 1921,[42] having settled into his teaching role at Caulfield Grammar School once again. He eventually graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1931,[43] and a Diploma in Commerce in 1933.[44][45]

Teaching (1907–1914)

Having taught at Wangaratta Grammar School in 1907, he went on to teach at another two schools in New South Wales — Tudor House School, Mona Vale and Chatswood Preparatory School — before returning to Melbourne in 1910, and entering the Victorian State Government Education Department's Teaching Service. He commenced teaching at Caulfield Grammar School in 1913, having been recruited by its owner and principal, Walter Murray Buntine (1866–1953), "from a small school in Gippsland",[46][47] to serve as a "Resident Master".

First A.I.F.

.tiff.png)

On 11 September 1914, soon after the declaration of war (4 August 1914), Lamb-Smith — "[whose] sympathy lay with healing people rather than wounding them" (Webber, 1981, p. 248) — enlisted in the A.I.F.,[48] and joined the Expeditionary Camp at Broadmeadows.

On 15 December 1914, having completed his basic training, he was appointed to the Second Field Ambulance, a unit that had been raised at Broadmeadows, in mid-August 1914. During the five years that he served in the A.I.F., Private Lamb-Smith was temporarily promoted on a number of occasions to fill vacancies caused by the vacations, leave, or deployment of others — including temporary Lance Corporal, temporary Corporal, and temporary Sergeant — then, once the individual he had replaced had returned, he reverted to his earlier rank.[49]

Landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915

As a member of the Second Field Ambulance, he landed at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915. The historians at the Australian War Memorial write of a "casualties debacle":

- During the day the medical services were overwhelmed. The suffering of the wounded was pitiful; many men died on the beach, and it is estimated that hundreds more lay in the hills out of the reach of help. Most notably, there were inadequate arrangements for the critically wounded, who could not be taken back to the ships until after all the troops and stores had been landed. It was early evening before boats became available; many of the maimed and bleeding were sent off in filthy barges.

- No one knows for sure how many Australians died on the first day, perhaps 650. Total casualties, including wounded, must have been about 2,000.[50]

Illness and injury

Lamb-Smith sought treatment for gastric illness from time to time at Gallipoli, and in November 1915 he was hospitalized in Egypt with a case of "Enteric Fever" (i.e., Typhoid fever), which was severe enough for him to be invalided back to Australia in December 1915,[51] where he recovered sufficiently, four months later, to be able to return to duty.[52] He rejoined the Second Field Ambulance, in France, in August 1916.

He was wounded-in-action in the left leg, in France, on 22 April 1917.[53] He was hospitalized for a month, released, and, then, re-admitted with a poisoned left leg five months later. He returned to active duty with the Second Field Ambulance in mid-December 1917, and continued to serve with them until the end of the war.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The A.I.F. Educational Scheme

The A.I.F. Education Scheme was created and administered by Brigadier-General George Merrick Long (1874–1930) — a former headmaster of Trinity Grammar School, in Victoria (1904–1911); and, at the time of his appointment as Director of Education, A.I.F., the Anglican Bishop of Bathurst — with the assistance, support, and guidance of Major Harry Thomson (1888–1933), a Rhodes Scholar, of Oxford and Adelaide Universities,[54] and Captain William James Mulholland (1888–1966), of Sydney University.[55] The Scheme had its origins in the A.I.F.’s response to the report made by Long in mid-1918:[56] at a time when it was obvious that it could take at least twelve months for the available transport to be able to repatriate all military personnel to Australia.[57]

Following his report, Long was commissioned to form the A.I.F.’s Education Service — which operated continuously from that time until late 1920 (at which time all of the overseas military personnel had been repatriated). Given that very few of its members were professional soldiers, and that all of its members were volunteers, the A.I.F. clearly understood its obligation to "refit the fighting man for his return to civil life and to make good as far as possible the wastage of the years spent at war" (Long, 1920, p. 141); and, in recognizing that "the longer the war goes on the more difficult becomes the [men's] taking up of the old life", its Education Scheme was specifically designed to meet the particular post-war needs of three quite different groups of men:[58]

- (a) those whose yet-to-be-completed occupational training had been abandoned upon their enlistment;

- (b) those who had enlisted at an early age and, as a consequence, had not yet begun to learn a trade or occupation — as well as those who, for other reasons (e.g., lack of opportunity), had not received any occupational training at all prior to their enlistment; and

- (c) those who, as a consequence of their A.I.F. experience, or as a consequence of technological developments, realized that they could not go back to their former occupation.

When applying for support from the scheme, the men provided particulars of their pre-enlistment occupation, their current military employment, their intended post-war occupation, the areas within which they desired training, and the details of any special courses of instruction that might prove beneficial. Training was freely available to all, always voluntary, and never compulsory. It was of a non-military nature, and was delivered to the men, as part of their individual post-war demobilization procedure, through two separate but inter-dependent programmes:[59]

- (a) "Internal": through in-service training, relying on the resources available within the A.I.F., conducted whist the individual remained within the army (and, moreover, this in-service training was also continued on the transport ships back to Australia, and only ceased on their disembarkation);[60]

- (b) "External": where the soldier, although on full-pay, was released from all military duty, and attended a university, college, school, workshop, farm, etc. in order to acquire specific skills or to undergo specific formal training.[61]

- Further, in relation to "undergraduate studies", the (greatly-overcrowded-with-individuals-returned-from service) British Universities were quite unable to service the needs of those still-overseas Australians desiring to resume/commence undergraduate studies. Recognizing this, General Sir John Monash, Commander of the Australian Forces, "granted early repatriation [to Australia] to undergraduates so that they might rejoin their Universities in March, 1919 … [in order] to save the wastage of still another year from [their] professional career" (Long, 1920, p145).

Lamb-Smith not only worked immediately post-war as one of the scheme's in-service instructors — remaining overseas such that he was in one of the last groups repatriated — but he also used the opportunity the scheme provided for him, as a career educator, to spend some time at King's College London where, he studied (among other things) the approach of Henry Caldwell Cook, a British ex-soldier and teacher at an all-boys school, whose work emphasized the importance of making learning an exciting, inspirational, and imaginative exercise for all involved.[62] Following that sojourn in England, he also studied in France, before returning to his instructional duties in Belgium, from whence he was repatriated on 6 October 1919.

Teaching at Caulfield Grammar School (1920–1951)

Lamb-Smith returned to Australia from his overseas service on 6 November 1919,[63][64] and was officially discharged from the A.I.F. on 4 February 1920.[65] Inspired to deliver his teaching with an entirely new outlook, and in an entirely new way, he resumed his teaching career at Caulfield Grammar School in the first term of 1920, although he was in a rather fragile state and greatly affected by his horrific wartime experiences as a member of the Field Ambulance.

- "He was a member of the Anzac forces at Gallipolii. He served on the Western Front, surviving all dangers throughout the war. … He carried in the bleeding remnants of dying friends and companions. He saw the bones protruding from wounded limbs, the smashed faces, the horrors of gas. … The long and terrible strain had insidious effects, and for long after the war his mind was tortured with the memory of the dreadful things he had seen. … In 1920 he returned to Caulfield, at first with a mind still tortured in itself." — (Webber, 1981, pp.248, 249)[66]

- "History [at Caulfield Grammar] was taught by Lamb Smith, whose nerves had deteriorated because of his experiences overseas during the First World War. He had something of [W.S.] Morcom's eagle-like profile, but softened by a less prominent jaw and a kindlier disposition. Fair hair sprouted from his high forehead, lines radiated from his blue eyes when he laughed. Although Smith was a kind man, when he did lose his temper all his self-control went with it."[67]

As an (already) experienced teacher of boys and young men, Lamb-Smith had been greatly influenced by his wartime observations of the prior education, wants, needs, talents, and native abilities of the men who enrolled in the AIF Education Scheme in order to prepare themselves academically, occupationally, and personally for their return to post-war civilian life (often in an entirely new and different occupation from that which they followed at the time of their enlistment).

Having directly observed these men collectively — most of whom had completed their secondary education some years earlier — he began to recognize the importance of teaching in a far more interesting and engaging fashion. Moreover, he also came to recognize the considerable impact of the wide range of useful skills the men had (incidentally) acquired as a consequence of their military service; both in terms of unlocking their (otherwise) hidden talents, and in terms of making them far more useful to themselves and their society.

Hobbies

School will occupy one of the most elaborate school clubhouses In Victoria.

Twelve years ago a few boys were encouraged by Mr. H. G. Lamb Smith,

a member of the school staff, to compare notes on their hobbies and to bring to-

gether examples of their work in order to interest other boys. From this this

small beginning a number of groups were formed, and under the stimulus of

an annual exhibition the hobbies club became an energetic body.

With the assistance of the dramatic society it obtained much useful equip-

ment for school and leisure activities.

For the last two years the club has been working to provide a headquarters

building, and the boys, with the support of the parents' committee, have now

raised a sufficient sum to enable a large clubhouse to be built.

Work will begin on the erection of the building at once. The site is being

prepared, and the boys will carry out much of the work under the guidance of

qualified instructors. The building will be completed early next year.

Contained In the building which will be about 80ft long, will be a workshop,

a craftroom, a darkroom, and a radio-room. An area near by will be set aside

for gardening and nature study. The parents' committee will help the boys to

provide equipment.

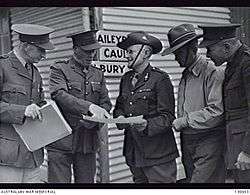

Cadet Corps

Some form of military training had been a part of the formal tuition at Caulfield Grammar School since its founding in 1881. When it officially raised its own Cadet Corps as a detachment of the Victorian Volunteer Cadet Corps on 3 March 1885,[68] it was the eighth school in Victoria to do so.[69] The Cadet Unit which had been completely disbanded in 1929,[70] was re-established, during wartime, in 1941. Lamb-Smith volunteered and was immediately made its O.I.C.[71] He continued in that role until December 1948.[72]

Other offices

In his lifetime he variously held the offices of lay Chairman of the (St Paul's) Cathedral Branch of the Church of England Men's Society,[75] President of the Old Caulfield Grammarians' Association, Chaplain of the Caulfield Grammarians' Masonic Lodge, the Treasurer of St James the Great Anglican Church, East St Kilda, Honorary Treasurer of the Victorian Amateur Athletic Association's Inter-Club Sports Committee,[76] and the Caulfield Branch of the All for Australia League.[77] He was a member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1914.[78]

Also, he was an active member of the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia (later, the Returned Sailors' Soldiers' and Airmens Imperial League of Australia), the Honorary Organizer of the Caulfield Grammar School's Memorial Hall Fund,[79] and, with his wife Dorothy, he worked actively for the Auxiliary of the Royal Children's Hospital.[80][81]

Remembrance and Thanksgiving at Caulfield Grammar School

Anzac Day

Among all of the Australian Schools, Caulfield Grammar School has an unusual, if not unique, relationship with 25 April.

- It is Anzac Day: the day that Australia, as a nation, commemorates the sacrifices of those who served in the armed forces, and honours their contributions to the nation, on the anniversary of the landing at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, on 25 April 1915 (at which Lamb-Smith, himself, had participated).

- It is the anniversary of the founding of Caulfield Grammar School, on 25 April 1881 — this is an extraordinary coincidence, for it is clear, from a number of different advertisements, that the school's founder, Joseph Henry Davies (1856–1890), had always intended to open the school on Wednesday, 20 April 1881;[84] however, just at the last minute, Davies postponed the opening until Monday, 25 April.[85][86][87]

Remembrance Day

The idea of a moment of silence at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month was first suggested by an Old Caulfield Grammarian, journalist Edward George Honey (1885–1922), in letter he wrote on 8 May 1919, to The Evening News of London.[88]

Death

Having discharged "the heavy responsibilities" of reading out the "names of the Fallen" (the majority of whom Lamb-Smith had directly known in person, the remainder by reputation) at Caulfield Grammar's annual Remembrance Day Ceremony in November 1951, Lamb-Smith returned to his office, "suffered a severe stroke, and collapsed" — "he lived on for some weeks, but never recovered from the illness", and died at his home in East St Kilda on 26 December 1951 (Webber, 1981, pp. 250–251).

Legacy

In a number of ways, Lamb-Smith's legacy is deeply embedded within Caulfield Grammar School:

- "The wide range of clubs and organizations, the varied extra-curricular activities now available to boys at Caulfield Grammar School is a direct result of this wonderful man." — (Weber, 1981, p. 249)

- A posthumous portrait, commissioned by the Caulfield Grammarians' Association in 1973, and painted by Noel Counihan (1913–1986), a former student of Lamb-Smith's,[89] now stands on permanent display in the Caulfield Campus's "Cripps Centre" — the building complex which, in 2005, replaced the Memorial Hall that had been destroyed by fire on "Cup Day" 2000.

- The wooden crafts and hobbies complex built in 1936, named Lamb Smith House in recognition of Lamb-Smith's influence,[90] was dismantled, stored, and removed from the Caulfield campus in 1954, when the land it occupied was needed to erect six new classrooms. It was carefully re-assembled a couple of years later at the school's Yarra Junction property. It served a number of different purposes over the years; and, in 1989, extensive renovations converted Lamb Smith House into a far more comfortable recreation area for students visiting the "YJ" campus.[91]

- A Lamb Smith Prize for Leadership is awarded to the most outstanding student leader during the school's leadership camps (which are conducted at the school's "YJ" campus).

Footnotes

- He was born at Dinas Bran, Wells Road, then Cheltenham, Victoria, (now Beaumaris, Victoria).

- He gave his family name as "Lamb-Smith"; sometimes others (including Caulfield Grammar) used "Lamb Smith". His university enrolment lists him as "Smith, Hugh Gemmell Lamb" (UOM, 1926, 1932, and 1934). His initial A.I.F. enlistment document (see HGLSd) also registered him as "Smith, Hugh Gemmell Lamb", despite the fact that he signed the enlistment form with "Gemmell LambSmith" (one word, capital "S", no hyphen) on 11 September 1914. In the process of his deployment with the Second Field Ambulance on 15 December 1914, at which time he was given the Service number 279, the family name on his military service record was amended to read "Lamb-Smith" (see HGLSd); and from that time, all of his service record documents identify him as "Lamb-Smith, H.G.". Also, after the war, he signed the separate official receipts (each of which identified him as "Lamb-Smith, H.G.") for his three service medals with "G LambSmith" (see HGLSd).

- The Age, 29 June 1915.

- A "housewife", also known as an Australian Army Sewing Kit, was issued to all personnel. It was a small pouch that contained everything a soldier might need to carry out any necessary repairs to his clothing. It contained a thimble, darning wool, linen thread wound around a card, needles, and replacement uniform and shirt buttons (see External images (below).

- The term "Gayboys" specifically refers to the bohemian painters in the Heidelberg School, who set up their "artist camps" along the banks of the Yarra River in order to engage in en plein air painting.

- Weekly Times, 13 April 1889.

- The Age, 28 December 1951.

- Prahran Telegraph, 28 May 1910.

- Oakleigh Leader, 18 March 1983.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 28 May 1910.

- Mornington Standard, 21 January 1892.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 18 March 1899.

- The Argus, 30 May 1910.

- AGG, 1902, 1907; and Johns (1908), p.46.

- The Age, 23 April 1883.

- Illustrated Australian News, 10 January 1880.

- Webber (1981), pp.246–247.

- The Argus, 24 June 1938.

- See The Argus, 19 May 1884, and 31 December 1945.

- Ballarat Star, 30 June 1910.

- See MMLSa, MMLSb, MMLSc, and MMLSd. Note that, as a member of the Australian Army Nursing Service, she had no service Number.

- MMLSd.

- The Australasian, 10 December 1921.

- See Farmer & Settler, 22 July 1955; and Sydney Morning Herald, 4 October 1960.

- C. of E. Messenger, 1 August 1904.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 10 August 1872, 24 June 1905, and 24 June 1914; Armidale Chronicle, 16 January 1897; and Murrumburrah Signal, 7 July 1905.

- "Births Search Results: Harris Dorothy". NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- PVH; Sydney Morning Herald, 6 November 1880, and 21 July 1917; and Brisbane Courier, 27 July 1917.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 19 December 1908.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 19 July 1924.

- The Age, 17 August 1964.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 31 January 1917; (Sydney) Evening News, 31 August 1918; and West Australian, 18 October 1919.

- From the newspaper accounts (especially Sydney Morning Herald, 31 January 1917, and 10 November 1919), and from her rank of quartermaster, and from the fact that she was a guest of the wife of the Governor-General, in Melbourne, whilst in transit to Sydney, it is clear that she was not in England as one of the voluntary Australian Red Cross medical orderlies, known as V.A.D.s (see Voluntary Aid Detachment).

- Also, note that the "Sister Harris" who travelled to France in early July 1916 with the Australian Jockey Club sponsored Red Cross team of "Bluebirds", was an entirely different individual: she was Fanny May Harris (1893–1964), a Warrnambool trained nurse.

- The Argus, 2 June 1953.

- Scotch College Archive records.

- Whilst at Scotch he performed well as an athlete (Under 14: The Age, 9 November 1901; Tennis, The Age, 16 December 1904) and won various prizes for his academic performance (IVB (Lower): The Age, 12 December 1902; Class IVB: The Argus, 16 December 1903)

- The Argus, 21 January 1908.

- At the 1908 Wangaratta Grammar School Speech Day, the headmaster commented that, in late 1907, Lamb-Smith had "completed the examination in which he has formerly passed some subjects at another school, and obtained distinction in history" (The Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 26 December 1908).

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 27 April 1907.

- UOM (1920), p.20; and UOM (1926), p.254.

- The Age, 12 January 1922.

- By coincidence, Lamb-Smith received his Bachelor of Arts in the same graduation ceremony as his CGS teaching colleague, Harold Pennefather (who had also attended CGS as a student 1912–1914, and went on to teach there from 1930 to 1969), received his Master of Arts: The Age, 20 April 1931; UOM, 1932, pp.1074 (Lamb-Smith), 1079 (Pennefather).

- The Age, 10 April 1933; UOM, 1934.

- At the 1933 speech night, the headmaster noted that, "the rapid development of our commercial side under Mr Lamb Smith, B.A, Dip. Com. has enabled us to teach intermediate accountancy" (The Argus, 13 December 1933).

- Webber (1981), p.247.

- Buntine was born in Gippsland, had also attended Scotch College, and had many professional and personal connexions within the Gippsland area.

- HGLSa; HGLSb; and HGLSc.

- See HGLSd.

- AWM-DOTL.

- HGLSd; and The Age, 23 December 1915.

- HGLSd; and The Argus, 4 April 1916.

- HGLSd; The Argus, 22 May 1917.

- The Register, 16 June 1919.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 3 December 1940.

- See Birdwood & Long, 1918.

- According to Grey (1999, p.115), at the time of the armistice (11 November 1918), there were 95,951 and 17,255 soldiers still serving in France and the Middle East (respectively), and 58,365 soldiers located in depots, bases, and hospitals in England — as well as those Australian nurses still serving in Salonika and India — all of whom required transportation back to Australia.

- Richmond River Herald, 27 September 1918.

- Long, 1920.

- Long (1920, p.145) notes that, in relation to the internal provisions of the scheme, there had been "126,000 attendances at lectures and classes during six weeks of April and May [1919]" (this included those who participated whilst in transit to Australia).

- Long (1920, p.145) states that "10,000 men were placed out for various periods in universities, colleges, workshops, farms, etc." under the scheme's external provisions.

- Cook's approach, which he termed as "the play way", stressed its central feature of using student created dramatic productions (i.e., rather than the term "play" meaning "games") as a vehicle for learning. His school also released six handbooks over an eight year period, known as the Perse Playbooks, containing various items produced by the school's pupils. (For details of Cook's approach, see Sydney Morning Herald, 5 January 1920 and, also, Cook (1917)).

- The Argus, 5 November 1919.

- Dorothy had returned, via Melbourne, to Sydney on a different transport, on 9 November 1919 (Sydney Morning Herald, 10 November 1919).

- HGLSd.

- Horace Webber's observations were based on his own direct experience of Lamb-Smith at Caulfield Grammar School: Webber had been a student of Lamb-Smith's in 1920, and had also been his teaching colleague from 1926 to 1945. Webber (p.248) notes that, "according to Patsy Adam Smith's The Anzacs, in no section was the casualty rate higher than among members of the Field Ambulance".

- Noel Counihan's personal recollection of Lamb-Smith (taken from Smith, 1993, p.45), who was his history teacher at Caulfield Grammar (in 1928), and the subject of Counihan's (1973) portrait that now hangs in the school's Cripps Centre.

- POV, 1887; The Advertiser, 28 May 1910.

- The Argus, 4 March 1885.

- According to Penrose (2006, p.42), compulsory military training for boys aged 12 to 14 was abolished in 1922, and for boys aged 15 to 18 in 1929.

- Webber (1881), p.250; and Penrose (2006), p.42.

- Provisionally promoted to Lieutenant on 24 February 1941 (AGG, 1941), he retired, with the temporary rank of Captain, on 31 December 1948 (AGG, 1949).

- At the extreme right of the photo is Lieutenant Herbert McDonell Shaw (1905–1990) (VX80952), Second AIF — see Service Record: Shaw, Herbert McDonell (VX80952) — an ex-student of Lamb-Smith's at Caulfield Grammar School, and Member of the Caulfield Grammar School Council from 1939 to 1978.

- See Senior Cadets: Camp Training this week, The Age, (Wednesday, 26 August 1942), p.2, Cadets go into Camp: Fine Response by Schools, The Age, (Saturday, 29 August 1942), p.3, and Cadets Settle Down in Camp: 8 Days’ Training, The Age, (Monday, 31 August 1942), p.3.

- The Argus, 4 December 1944. The President of the Cathedral Branch, Dean Henry Thomas Langley (1877–1968), who had attended Caulfield Grammar School in the 1890s, served on the Council of Caulfield Grammar School from 1931 to 1945 (Webber, 1981, pp.277, 301).

- The Age, 26 November 1948.

- The Age, 3 December 1931; the President of the branch was Walter Murray Buntine, headmaster of Caulfield Grammar School (The Argus, 25 March 1931).

- List of Members: Melbourne, 1914, BAAS (1915), p.128.

- The Argus, 11 October 1946.

- The Age, 19 November 1941.

- See Obituary, The Age, 28 December 1951, and Webber (1981), pp.246–251.

- Lithgow Mercury, 14 May 1915.

- The verse was first published in a letter to the Editor of the London Morning Post in early 1915. Its author, "Mrs. Nesta Blennerhassett" – viz., Clara Nesta Richarda Blennerhassett (1864–1945) — was a Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse in World War I; she was awarded MBE in January 1918.

- See, for example, The Argus, 2 April and 9 April 1881.

- See, for example, The Argus, 19 and 20 April 1881.

- Although no reason for the postponement was ever provided, it may simply be because, even though Davies had become (academically) qualified for the award of the degree in March 1881 (see The Argus, 24 November 1880, 24 March 1881), he would not have been (technically) entitled to present himself as a "Bachelor of Arts" until the degree had been officially conferred upon him (either in person or in absentia) — and that he had been physically given his official testamur bearing the University's seal — at a formal graduation ceremony . He graduated B.A. on Saturday, 23 April 1881 (see The Argus, 25 April 1881).

- A further extraordinary (much later) coincidence: Stephen Hibbert Newton, the eighth headmaster of Caulfield Grammar School (from 1993 to 2011) was born on 25 April 1955.

- The West Australian, 11 November 1931; Australian Women's Weekly, 12 November 1969; DVAa.

- Dimmack (1974), p.125; Smith, R. (1981), p.33; and Smith, B. (1993), p.45.

- The Argus, 10 October 1936; and The Age, 12 October 1936.

- See CGS, 2010 for its location at "YJ".

References

Newspapers

- Marriages: Harris—Ross, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 10 August 1872), p.7.

- The Late Mr. H.M.C. Gemmell (Portrait), Illustrated Australian News, (Monday, 10 January 1880), p.5.

- The Late Mr. H.M.C. Gemmell (Obituary), Illustrated Australian News, (Monday, 10 January 1880), p.10.

- Births: Harries, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 6 November 1880), p.1.

- University of Melbourne: Third Year Arts, The Argus, (Wednesday, 24 November 1880), p.7.

- The University of Melbourne: Honour Examination, The Argus, (Thursday, 24 March 1881), p.6.

- Tutors, Governesses, Clerks, &c: Caulfield Grammar School, The Argus, (Saturday, 2 April 1881), p.1.

- Educational: Caulfield Grammar School, The Argus, (Saturday, 9 April 1881), p.11.

- Tutors, Governesses, Clerks, &c: Caulfield Grammar School, The Argus, (Tuesday, 19 April 1881), p.1.

- Tutors, Governesses, Clerks, &c: Caulfield Grammar School, The Argus, (Wednesday, 20 April 1881), p.1.

- University of Melbourne: The Annual Commencement, The Argus, (Monday, 25 April 1881), p.6.

- Marriages: Smith—Gemmell, The Age, (Monday, 23 April 1883), p.1.

- Births: Smith, The Argus, (Monday, 19 May 1884), p.1.

- (News in Brief), The Argus (Wednesday, 4 March 1885), p.5.

- Announcements: Births, The Weekly Times, (Saturday, 13 April 1889), p.11.

- Erica Society, The Brighton Southern Cross, (Saturday, 18 March 1899), p.3.

- Cheltenham Lawn Tennis Club, The Mornington Standard, (Thursday, 21 January 1892), p.3.

- Borough of Armidale, The Armidale Chronicle, (Saturday, 16 January 1897), p.5.

- Shire of Moorabbin, The Oakleigh Leader (Saturday, 18 March 1898), p.5.

- The Cadet Corps System, The (Adelaide) Advertiser, (Tuesday, 28 May 1901), p.7.

- Scotch College Sports, The Age, (Saturday, 9 November 1901), p.13.

- Scotch College, The Age, (Friday, 12 December 1902), p.9.

- Scotch College, The Argus, (Wednesday, 16 December 1903), p.4.

- Confirmations: June 21st, St.George's, Malvern, The Church of England Messenger for Victoria and Ecclesiastical Gazette for the Diocese of Melbourne, (Monday, 1 August 1904), p.88.

- Scotch College, The Age, (Friday, 16 December 1904), p.8.

- Deaths: Harris, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 24 June 1905), p.10.

- Death of Mr W. M. Harris, The Murrumburrah Signal and County of Harden Advocate, (Friday, 7 July 1905), p.2.

- Advertisement: Wangaratta Grammar School, The Ovens and Murray Advertiser, (Saturday, 27 April 1907), p.7.

- University of Melbourne: Public and Matriculation Examinations: Successful Candidates: Junior Public Examination: Country Candidates, The Argus, (Tuesday, 21 January 1908), p.7.

- Kindergarten Training College, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 19 December 1908), p.17.

- Wangaratta Grammar School: Speech Day, The Ovens and Murray Advertiser, (Saturday, 26 December 1908), p.10.

- Obituary: Ex-Cr. Wm. Lamb Smith, The Brighton Southern Cross, (Saturday, 28 May 1910), p.4.

- Personal, The Prahran Telegraph, (Saturday, 28 May 1910), p.5.

- Rifle Notes, by Marker, The Argus, (Monday, 30 May 1910), p.5.

- Nurses' Examination: Successful Candidates: Children's Hospital, The Ballarat Star, (Thursday, 30 June 1910), p.1.

- Deaths: Harris, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 24 June 1914), p.6.

- Items of Interest, The Lithgow Mercury, (Friday, 14 May 1915), p.6.

- Soldiers' Letters: Teeth-Testing Rations, (Tuesday, 29 June 1915), p.5.

- Caulfield Grammar School: Roll of Honour, The Argus, (Tuesday, 27 July 1915), p.8.

- God Bless Our Splendid Men, The Leader, (Saturday, 4 December 1915), p.41.

- Sick and Wounded: A Further List of Victorians: 2nd. Fld. Amb., The Age, (Thursday, 23 December 1915), p.8.

- Australian Casualties: 160th List Issued: Returned to Duty, The Argus, (4 April 1916), p.5.

- Anzac Commemoration: Observance in Schools, The Argus, (Saturday, 22 April 1916), p.16.

- From Near and Far, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Wednesday, 31 January 1917), p.5.

- Anzac Anniversary: Commemoration in Schools, The Argus, (Wednesday, 25 April 1917), p.9.

- Australian Casualties: List No.301: Wounded: Victoria, The Argus, (22 May 1917), p.8.

- Roll of Honour: Harris, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 21 July 1917), p.12.

- Personal Notes, The Brisbane Courier, (Friday, 27 July 1917), p.7.

- Fair Sydney Nurses, The (Sydney) Evening News, (Saturday, 31 August 1918), p.2.

- The A.I.F. Education Scheme, The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser, (Friday, 27 September 1918), p.2.

- Educating the Soldiers: Major Thomson on Things Accomplished, The (Adelaide) Register, (Monday, 16 June 1919), p.5.

- A.I.F. Education Scheme: Work Done in England: Excellent Results Achieved, The Age, (Tuesday, 17 June 1919), p.5.

- Returning Soldiers: Osterley List: Non-Members, The West Australian, (Saturday, 18 October 1919), p.8.

- Troops returning: Expected Arrivals: On S.S. Pakeha: Nursing Staff, The Argus, (Wednesday, 5 November 1919), p.6.

- Personal, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Monday, 10 November 1919), p.6.

- Soldiers at School: Wide Field of Work Education, The Argus, (Wednesday, 31 December 1919), p.6.

- The New Teaching: At Cambridge: The Perse School, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Monday, 5 January 1920), p.6.

- What the A.I.F. Educational Scheme in Europe Meant: Explained by Brigadier-General W. Ramsay McNicoll, C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O., C.O.G., The Urana Independent and Clear Hills Standard, (Friday, 30 January 1920), p.4.

- Marriages: Sloane—Lamb-Smith, The Australasian, (Saturday, 10 December 1921), p.3.

- University of Melbourne: December Annual Examination, 1921: Ordinary Degree: Arts: Passed in One Subject, The Age, (Thursday, 12 January 1922), p.7.

- "Lest We Forget" — Victoria Commemorates Anzac Deeds, The Argus, (Thursday, 26 April 1923), p.7.

- Marriages: Lamb Smith—Harris, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 19 July 1924), p.14.

- School Speech Days: Caulfield Grammar: Record Year Concluded, The Argus, (Tuesday, 13 December 1927), p.13.

- Caulfield Grammar School, Malvern Standard, (Thursday, 11 December 1930), p.5.

- Caulfield Grammar School: The School's Future, The Age, (Friday, 12 December 1930), p.6.

- All For Australia: League Growing Rapidly: Meeting at Caulfield To-night, The Argus, (Wednesday, 25 March 1931), p.8.

- Conferring of Degrees: Bachelor of Arts, The Age, (Monday 20 April 1931), p.8.

- Civic Services: Caulfield Grammar School, The Age, (Monday, 27 April 1931), p.8.

- Origin of a Great Idea, The West Australian, (Wednesday, 11 November 1931), p.13.

- Meetings and Lectures, The Age, (Thursday, 3 December 1931), p.3.

- The University: Conferring of Degrees: Diploma in Commerce, The Age, (Monday, 10 April 1933), p.11.

- Associated Grammar Schools, The Age, (Wednesday, 26 April 1933), p.10.

- Caulfield Grammar School: 52nd Anniversary, The Argus, (Wednesday, 26 April 1933), p.12.

- School Speech Nights: Caulfield Grammar School, The Age, (Wednesday, 13 December 1933), p.17.

- Associated Grammar Schools, The Age, (Thursday, 26 April 1934), p.8.

- Associated Grammar Schools, The Age, (Friday, 26 April 1935), p.10.

- Services in Many Schools: Lessons of Sacrifice and Loyalty: Remembrance of the Fallen: Associated Grammar Schools, The Argus, (Friday, 26 April 1935), p.9.

- The Schools: Hobbies Clubhouse, The Argus, (Thursday, 12 December 1935), p.14.

- Notes from Classroom and Playing Field: Caulfield Hobbies Club, The Argus, (Saturday, 10 October 1936), p.33.

- Caulfield Grammar: Hobbies House Opened, The Age, (Monday, 12 October 1936), p.10.

- For Young People: Among the Schools: Extra Class Activities, The Age, (Tuesday, 13 October 1936), p.3.

- In the Schools, The Age, (Tuesday, 26 April 1938), p.6.

- Caulfield Grammar: 57 Years Old Yesterday, The Age, (Tuesday, 26 April 1938), p. 7.

- In the Schools: Caulfield Grammar, The Argus, (Tuesday, 26 April 1938), p.3.

- Obituary: Mrs. W. Lamb Smith, The Argus, (Friday, 24 June 1938), p.2.

- The Schools: Pictures of "The Landing", The Argus, (Friday, 26 April 1940), p.7.

- Army Education Service: A Need in the New A.I.F.: Experience of the Great War, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Tuesday, 3 December 1940), p.8.

- Packing Hampers, The Age, (Wednesday, 19 November 1941), p.4.

- Personal, The Argus, (Monday, 4 December 1944), p.2.

- Deaths: Sloane, The Argus, (Monday, 31 December 1945), p.2.

- Caulfield Grammar To Have Memorial Hall, The Argus, (Friday, 11 October 1946), p.3.

- Wrong Idea About Park, The Age, (Friday, 26 November 1948), p.8.

- Deaths: Lamb-Smith, The Age, (Friday, 28 December 1951), p.2.

- Obituaries: Mr. H Lamb-Smith, The Age, (Friday, 28 December 1951), p.2.

- Coronation Medal Awards list: Mrs. Dorothy L. Smith, The Argus, (Tuesday, 2 June 1953), p.15.

- Jervis, James, "Recalling the Pioneers: No.36—Alexander Sloane", The Farmer and Settler, (Friday, 22 July 1955), p.17.

- Deaths: Sloane, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Tuesday, 4 October 1960), p.36.

- Deaths: Lamb Smith, The Age, (Monday, 17 August 1964), p.16.

- He Originated Silent Tribute to the Fallen, The Australian Women's Weekly, (Wednesday, 12 November 1969), p. 67.

Others

- (2FA-WD) Australian Imperial Force: War Diaries of Second Australian Field Ambulance (April 1915 – April 1919).

- (AGG, 1902) Appointment of Consul-General for Paraguay in the Commonwealth of Australia, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No.46, (Friday, 26 September 1902), p.503.

- (AGG, 1907) Resignation, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No.96, (Saturday, 21 December 1907), p.1461.

- (AGG, 1941) Australian Military Senior Cadets: Southern Command: 3rd Military District, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No.96, (Thursday, 15 May 1941), p.1029.

- (AGG, 1949) Australian Military Senior Cadets: Southern Command: 3rd Military District: 3rd Cadet Brigade: 22nd Cadet Battalion, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No.29, (Thursday, 28 April 1949), p.1091.

- (AWM-DOTL) Dawn of the Legend: The Failed Plan: 25 April 1915: The Casualties Debacle, Australian War Memorial, n.d.

- (BAAS, 1915) List of Members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1914, British Association for the Advancement of Science, (London), 1915.

- (CGA, 2011) "The Story of Caulfield Grammar School (1958)", section of the Video Presentation made to the (1950s) Caulfield Grammarians' Association Dinner on 3 June 2011. Video on YouTube: (a) the (c.1958) amateur movie (most likely produced by a hobby group at CGS) commences at 5:33; (b) the section 8:01–8:46 features various aspects of "Hobbies"; and (c) 8:02–8:07 is footage of Hugh Gemmell Lamb-Smith.

- (CGA, 2016) Moran, Daryl, "Forgotten stories of Caulfield and Malvern Grammarians in the First World War", A Presentation to the Caulfield Grammarians' Association's Archer and Marsden Chapter Luncheon, 23 October 2015: Video on YouTube

- (CGS, 2010) Caulfield Grammar School: Yarra Junction Campus: 2010 Colour Map.

- (DVAa) Origin of Remembrance Day: Observation of Silence at 11 AM, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra.

- (HGLSa) First World War Nominal Roll: Corporal Hugh Gemmell Lamb-Smith (279) Second Field Ambulance.

- (HGLSb) First World War Embarkation Rolls: Lamb-Smith, Hugh Gemmel.

- (HGLSc) "Lambsmith, 279, H.G.", Roll of Honour: Casualties in the Australian Imperial Force: List dated May 16, 1917: N.C.O.’S and Men: Wounded: Army Medical Corps, The Anzac Bulletin, No.21, (London, 30 May 1917), p.15.

- (HGLSd) AIF Service Record: Lamb-Smith, Hugh Gemell (279).

- (MMLSa) First World War Nominal Roll: Sister Mora Mary Smith A.A.N.S.

- (MMLSb) First World War Embarkation Rolls: Smith, Mora Mary Lamb.

- (MMLSc) Smith, Mora Marie Lamb: Australian Nurses in World War I (Small-Smythe), 2013.

- (MMLSd) AIF Service Record: Smith, Mora Marie Lamb.

- (POV, 1887) Parliamentary Paper No.71: Regulations for Victorian Volunteer Cadet Corps (Amended), Parliament of Victoria, (Melbourne), 1887.

- (PVH) AIF Service Record: Harris, Philip Vernon (577).

- (UOM, 1920) Roll of War Service, The Melbourne University Magazine: War Memorial Number, (July 1920), pp.7–23.

- (UOM, 1926) Roll of Service Overseas 1914–1918: Roll of the Returned, Record of Active Service of Teachers, Graduates, Undergraduates, Officers and Servants in the European War, 1914–1918, University of Melbourne, (Melbourne), 1926, pp. 57–292.

- (UOM, 1932) "Degrees Conferred 1930–31: 18th April, 1931: Bachelor of Arts", University of Melbourne Calendar 1932, University of Melbourne, p.1074; "Master of Arts", p.1079.

- (UOM 1934) "Degrees Conferred 1932–33: 8th April, 1933: Diploma in Commerce", University of Melbourne Calendar 1934, University of Melbourne, p.1228.

- Adam-Smith, Patsy, The Anzacs, Thomas Nelson Australia, (West Melbourne), 1978.

- Birdwood, William R. & Long, George M., The A.I.F. Educational Scheme, Australian Imperial Force Print, 1918. (At pp. 5–13 of )

- Cook, Henry C., The Play Way: An Essay in Educational Method, William Heinemann, (London), 1917.

- Dimmack, Max, Noel Counihan, Melbourne University Press, (Carlton South), 1974.

- Grey, Jeffrey, A Military History of Australia (Revised Edition), Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1999.

- Johns, Fred, Johns's Notable Australians, and Who is Who in Australasia: A Dictionary of Biography Containing Records of the Careers of Men and Women of Distinction in the Commonwealth of Australia and the Dominion of New Zealand, Fred Johns, (Rose Park, Adelaide), 1908.

- Long, George M., "The A.I.F. Education Service", The Melbourne University Magazine: War Memorial Number, (July 1920), pp.143–147.

- Moran, Daryl, "A Noble Son Fall'n to Earth – The Short Life of Lt. Lyle Buntine MC", Military History and Heritage Victoria, 2016.

- Penrose, Helen, Outside the Square: 125 Years of Caulfield Grammar School, Melbourne University Publishing, (Melbourne), 2006. ISBN 0-522-85319-6

- Smith, Bernard, Noel Counihan: Artist and Revolutionary, Oxford University Press, (Melbourne), 1993. ISBN 0-19-553587-1

- Smith, Robert, Noel Counihan Prints 1931–1981: A Catalogue Raisonné, Hale & Iremonger (Sydney), 1981. ISBN 0-908094-80-9

- Thornton, Katherine, The Messages of Its Walls and Fields: A History of St Peter's College, 1847 to 2009, Wakefield Press, (Kent Town), 2010. ISBN 978-1-86254-922-7

- Webber, Horace, Years May Pass On . . . Caulfield Grammar School, 1881–1981, Centenary Committee, Caulfield Grammar School, (East St Kilda), 1981 ISBN 0-9594242-0-2

- Wilkinson, Ian R., The Fields At Play – 115 Years of Sport at Caulfield Grammar School 1881–1996, Playright Publishing, (Carringbah), 1997 ISBN 0-949853-60-7

- Wilson, Mary, The Making of Melbourne’s Anzac Day, Vol.20, No.2, (August 1974), pp. 197–209. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1974.tb01113.x