House of Dahn

Dahn, also Tan, Tann or Thann, is the surname of a noble family from the Palatinate region of Germany.

Name

The name Dahn, Tan, Tann or Thann often occurs in these variations as a surname. For example, there is also a Franconian aristocratic family, the von Tanns. The person who is often named in the literature as the progenitor of the lords of Dahn, Anshelmus de Tannicka, is clearly not connected to the Palatine Dahns, but just bore a similar name.

Ministeriales of the bishops of Speyer

It is probable that the Dahns who resided in the southern Palatinate Forest had not migrated there from elsewhere, but were a long-established family. They appear several times in late 12th century records as imperial ministeriales, but later acted more often as ministeriales for the bishops of Speyer. A ministerialis was someone appointed to work for an important clerical or secular lord. They were originally unfree knights who were used by their masters to manage their estates. Some of them made careers in the management and administration for their masters and rose in social standing, leaving their former unfree status behind them. An old fief of the Dahns was mentioned in 1285, which the family was granted by the Bishopric of Speyer in Hinterweidenthal, near the town of Dahn and which came from the imperial abbey of Hornbach. It is therefore quite possible that the southwest Palatine or Wasgau Dahns originally came from the retinue of the abbey at Hornbach. This connexion may be the reason that the Dahns were initially employed as imperial ministeriales and then increasingly as ministeriales to the bishop.

Castles of Dahn

To begin with, the family seat of the Dahns was probably Altdahn Castle. The first record of a castle seat on 3 May 1285, however, relates to Neudahn Castle (also enfeoffed by Speyer), as is evident from a list of the estates. The three castles at Dahn, especially Altdahn and Tanstein must have been older than that, however.[1] Until 1327, all the castles on the ridge above Dahn were referred to as "Than Castle" (Burg Than); only later were they given separate names. Occasionally even Tanstein was referred to as Old Than (Alt-Than). In 1288, four knights of Dahn at the burg zu tan were mentioned in a deed: Conrad III Mursel, John I, Henry IV Sumer and Conrad IV of Dahn. The amount of space they needed must have been considerable, which is why all five castle rocks were built on; Altdahn and Tanstein probably being the oldest elements, hence why there are fewere references to them.

Neudahn, which was built further away from the main castle group, was first mentioned in 1340 as nuwenburg zu Than.[1] The early history of the ministeriales of Dahn is largely unclear due to the complex ownership and family relationships.[2]

The first known recipient of the Dahn fief was Frederick I of Dahn between 1198 and 1236. At that time the castle was already an episcopal enfeoffment. From Berwartstein Castle, which was close by, we know that Emperor Frederick I gifted it in 1152 to the Bishopric of Speyer as a reward for their support.[3] This imperial castle (Reichsburg) thus became an episcopal fief-castle for the imperial ministeriales (Reichsministerialen) and, later, the ministeriales of the bishop. A similar situation may have pertained to the fief at Dahn.[4]

On the death of John I of Dahn in 1319 the family lost control over the third castle, Grafendahn, situated between Altdahn and Tanstein. After a feud over the inheritance the Bishop of Speyer re-enfeoffed the estate and it went to the counts of Sponheim.

In the early 15th century the knights of Dahn ran into difficulties. John VII and his brother, Henry X, of Dahn refused to attack Tannenberg Castle with Count Palatine Rupert III because members of the family lived in the castle. The king had Neudahn Castle seized, although it was later returned. Henry XIII of Dahn zu Tanstein was a follower of Franz von Sickingen. In the wake of the Sickingen Feud, Tanstein Castle was occupied by troops from Electoral Trier and not returned until 1544.

Towards the end of the Middle Ages the Dahn castles lost their significance and fell into ruins. Louis II of Dahn had a small schloss built in Burrweiler; this was first mentioned in 1571. Only a gate arch remains today.[5] The Dahns died out after Louis II of Dahn died in 1603 in Burrweiler. The fief then went back to the Bishopric of Speyer.

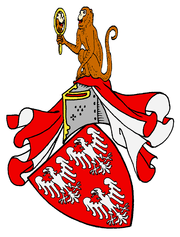

Coat of arms

The von Tann coat of arms consists of three silver eagles (2:1) on a red field.[6] On the helmet with its red and silver mantle is a monkey holding a mirror in its right hand.

Coat of arms of Bishop Conrad IV of Tann

The prince-bishop's coat of arms of Conrad IV of Tann as Bishop of Speyer (1233–1236) is usually quartered. The fields of the coat of arms alternate the family coat of arms of the von Tanns with the coat of arms of the Bishopric of Speyer, a silver cross on a blue field.

Literature

- Stefan Grathoff: Die Dahner Burgen. Alt-Dahn – Grafendahn – Tanstein. Führungsheft 21. Edition Burgen, Schlösser, Altertümer Rheinland Pfalz. Schnell und Steiner, Regensburg, 2003. ISBN 3-7954-1461-X

- Alexander Thon (ed.): ...wie eine gebannte, unnahbare Zauberburg. Burgen in der Südpfalz. 2nd improved edn. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg, 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1570-5 pp. 19–25,31,113.

References

- Grathoff 2003 p. 6

- Thon 2005 p. 113.

- Thon 2005 p. 31.

- Grathoff 2003 p. 4.

- burrweiler.de

- Hans Ammerich: Das Bistum Speyer und seine Geschichte, Band 2: Von der Stauferzeit (1125) bis zum Beginn des 16. Jahrhunderts; Kehl am Rhein, 1999; ISBN 3-927095-44-3. pp. 4–6.