House of Bellême

* This article is based in part on a translation of the article fr:Famille de Bellême from the French Wikipedia on 19 July 2012.

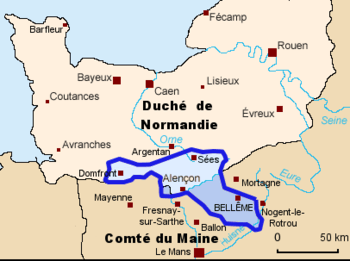

House of Bellême also referred to as the Family of Bellême was an important seigneurial family during the 10th through the 12th centuries. Members of this family held the important castles of Bellême, Alençon, Domfront and Sées as well as extensive lands in France, Normandy and Maine.

Rapid rise to prominence

The first known progenitor of this family is Yves de Bellême who was probably the son of Yves de Creil,[lower-alpha 1][1] The caput of the lordship was the castle of Bellême, constructed "a quarter of a league from the old dungeon of Bellême" in Maine.[2] The second lord, William of Bellême, with the consent of Richard I, Duke of Normandy constructed two castles, one at Alençon and the other at Domfront, the caput of the lordship remained the castle of Bellême.[2] Yet in a charter to the abbey of Lonlay of the lands of Neustria Pia, he describes himself as William princeps and provinciae principatum gerens indicating he considered himself an independent ruler or prince of his own domains.[3] His sons Fulk and Warin died in his lifetime leaving Robert as his heir.[4] Robert de Bellême died a prisoner leaving the fourth son, Ives as lord of Bellême, who shortly thereafter became Bishop of Séez.[5] William Talvas, held the lands of Bellême in right of his brother Bishop Ives who retained the Lordship himself until his death at which time William came into possession of the lands of Bellême, Domfront and Alençon.[6] After the infamous incident (see below) with William fitz Giroie, his kinsmen sacked and destroyed the lands of William Talvas who would not face them in the field.[7] In turn Talvas' son Arnulf rebelled and exiled his father, now reviled by everyone.[7] He wandered until he was taken in by the de Montgomery family whose son Roger agreed to marry his daughter Mabel in return for the lands William lost.[8] Mabel inherited all the vast estates of her father (and in 1079 those of her uncle Bishop Ives) and married the heir of one of the most prominent families in Normandy, Roger de Montgomery, who became the 1st Earl of Shrewsbury.[9]

Apogee and decline

Mabel was succeeded by her son Robert of Bellême, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury, who continued the aggressive policy of his mother. He built several castles to ensure control of the vast lordship of Bellême and held in total forty castles, including those of Alençon and Bellême, defends the territory and form a barrier to any attempt to bid. In 1098 Robert's younger brother Hugh died, and Robert inherited, on payment of £3,000 in relief, the English properties that had been their father's, including the Rape of Arundel and the Earldom of Shrewsbury.[10] Robert had also acquired the countship of Ponthieu jure uxoris and the honor of Tickhill; all of which combined made him the wealthiest magnate in both England and Normandy.[10] Robert rebelled repeatedly against the King of England and Duke of Normandy. In 1112 Robert was sent as an envoy of the French king to Henry I at his court at Bonneville whereas Henry seized Robert and imprisoned him.[11] Robert spent the rest of his life as a prisoner; the exact date of his death is not known.[12]

Bellême family bishops

Even as early as the latter half of the tenth century members of this family held the bishoprics of Le Mans and Séez. Seinfroy (Seginfredus) sought the bishopric of Le Mans and offered Geoffrey I, Count of Anjou the hamlet of Coulaines and the villa of Dissay-sue-Courcillon including all fiscal rights if he could use his influence. Geoffrey interceded with King Lothair to obtain the see for Seinfroy who became Bishop c. 970-71.[13] Geoffrey's choice of bishop proved to be a useful ally against the counts of Maine.[14] Although their parentage is unknown, his sister, Godeheut, was the wife of Yves de Bellême.[15] He was followed as Bishop of Le Mans in 997 by his nephew, Avesgaud de Bellême, son of Godeheut and Yves de Bellême.[16] Throughout most of his reign as bishop he and Herbert Wakedog were locked in a bitter and seemingly endless power struggle.[17] At Avesgaud's death in 1036 his nephew Gervais de Bellême, son of his sister Hildeburge de Bellême succeeded him as Bishop of Le Mans.[18]

Notoriety

The chroniclers of ducal Normandy, William of Jumieges and Orderic Vitalis depict several members of the family as cruel and deceptive. While William Talvas was as treacherous and self-serving as any of his family before him he surpassed them in wickedness and cruelty.[19] He had married a Hildeburg, daughter of a nobleman named Arnulf, but he had his wife strangled on her way to church, according to Orderic, because she loved God and would not support his wickedness.[19] Then on the occasion of his second wedding, William Talvas invited one of his vassals William fitz Giroie to attend. Suspecting nothing, fitz Giroie, while a guest at the festivities, was suddenly seized by Talvas' men and imprisoned, then according to Orderic horribly mutilated and blinded before being released. Somehow William Giroie survived his torture and mutilation and retired to Bec Abbey to live out the remainder of his life as a monk.[20]

Of all of Orderic's female subjects William's daughter Mabel was the most cunning and treacherous; if not entirely for her own misdeeds then as the mother of Robert de Bellême, who had a reputation for savagery as well as cruelty.[21] In one passage Orderic describes her as "small, very talkative, ready enough to do evil, shrewd and jocular, extremely cruel and daring.[22] Mabel was hostile to most members of the clergy; but her husband loved the monks at Saint-Evroul so she found it necessary to be more subtle.[23] She deliberately burdened their limited resources by visiting the abbey for extended stays with a large retinue of her soldiers. When rebuked by Theodoric the abbot for her callousness she snapped back that the next time she would visit with an even larger group. The abbot predicted that if she did not repent of her evilness she would suffer great pains and that very evening she did.[23] She left the abbey in great haste as well as in great pain and did not abuse their hospitality again.[23] In continuing her family's feud with the Giroie family she set her sights on Arnold de Echauffour, she son of William fitz Giroie who her father had mutilated at his wedding celebration.[24] She attempted to poison Arnold of Echauffour by placing it in a glass of wine but he declined to drink.[24] Her husband's brother, Gilbert, refreshing himself after a long ride, drank the wine and died shortly thereafter.[24] In the end though she bribed Arnold's chamberlain providing him with the necessary poison, this time being successful.[24] In 1077 she took the hereditary lands of Hugh Bunel by force.[25] Two years later while resting after a bath, she was murdered in her bed by the same Hugh Bunel[26]

But, Orderic Vitalis may have been most strongly biased against Robert de Bellême and his treatment of that magnate belies a moral interpretation of his actions.[27] The basis for Orderic's animosity towards Robert and his de Bellême predecessors was the longstanding and bitter feud between the Giroie family, patrons of Orderic's Abbey of Saint-Evroul, and the de Bellême family.[28] William Talvas (de Bellême), Robert's grandfather, had blinded and mutilated William fitz Giroie.[lower-alpha 2][8] Robert did at times appropriate church properties and was not a major donor to any ecclesiastical house. But Robert's attitudes toward the church are typical of many of his contemporaries; certainly no worse than the secular rulers and other magnates of his day.[29] The assessment of William II Rufus by R.W. Southern could well apply to Robert de Bellême as well: "His life was given over to military designs, and to the raising of money to make them possible; for everything that did not minister to those ends he showed a supreme contempt".[29]

Prominent members

The five generations of this well-known if not notorious family are represented by:

- Yves de Bellême

- Avesgaud de Bellême, Bishop of Le Mans

- William 'Princeps' de Bellême

- Ives de Bellême, Seigneur de Bellême and Bishop of Sées

- William I Talvas

Notes

- Yves de Criel and Yves de Bellême are confused by several sources and thought to be the same person by some. Yves de Criel, who was instrumental in saving young Richard I of Normandy would not chronologically be possible to be the same as Yves de Bellême, the subject of this article, who died c. 1005. Geoffrey White believed Yves de Criel was probably the father of Yves de Bellême, which was also accepted by all the French writers, but was of the opinion it should not be stated as fact as it was by Prentout. See: Geoffrey H. White, The First House of Bellême, TRHS, Vol. 22 (1940), pp. 70-71.

- For more on the feud between the Bellêmes and the Giroies see the article William I Talvas

References

- Geoffrey H. White, The First House of Bellême, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fourth Series, Vol. 22 (1940), p. 73

- Thomas Stapleton, Magni Rotuli Scaccarii Normanniae sub Regibus Angliae, Tomis I (Sumptibus Soc. Antiq. Londinensis, Londini, 1840), p. lxxii

- Kate Norgate, England Under the Angevin Kings, Vol. I (Macmillan and Co., New York, 1887), p. 114 & n. 1

- Geoffrey H. White, 'The First House of Bellême', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fourth Series, Vol. 22 (1940), p. 78

- Geoffrey H. White, 'The First House of Bellême', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fourth Series, Vol. 22 (1940), p. 81

- Jean Jacques Gautier, Histoire d'Alençon (Poulet-Malassis, Imprimeur-Libraire, Place Bourbon, 1805), p. 24

- The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Vol. II, Ed. & Trans. elisabeth M.C. Van Houts (The Clarendon Press, Oxford & New York, 1995), pp. 110-12

- Geoffrey H. White, 'The First House of Bellême', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fourth Series, Vol. 22 (1940), p. 84

- George Edward Cokayne, The Complete Peerage; or, a History of the House of Lords and all its Members from the Earliest Times, Volume XI, Ed. Geoffrey H. White (The St. Catherine Press, Ltd., London, 1949), p. 686 & note (j)

- C. Warren Hollister, Henry I (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2003), p. 155

- Kathleen Thompson, 'Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Bellême', Journal of Medieval History, Vol. 20 (1994), p. 138

- J. F. A. Mason, 'Roger de Montgomery and His Sons (1067-1102)', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th series vol. 13 (1963) p. 24

- Bernard S. Bachrach, 'Geoffrey Greymantle, Count of the Angevins, 960-987', State Building in Medieval France (Brookfield, VT & Aldershot Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 1995), III, 25-6

- Bernard S. Bachrach, 'Geoffrey Greymantle, Count of the Angevins, 960-987', State Building in Medieval France (Brookfield, VT & Aldershot Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 1995), III, 26

- Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band III Teilband 4 (Marburg, Germany: Verlag von J. A. Stargardt, 1989), Tafel 636

- Kate Norgate, England Under the Angevin Kings, Vol. I (Macmillan and Co., New York, 1887), p. 204.

- Jean Jacques Gautier, Histoire d'Alenτon (Poulet-Malassis, Imprimeur-Libraire, Place Bourbon, 1805), p. 24

- Steven Fanning, 'A Bishop and His World Before the Gregorian Reform: Hubert of Angers, 1006-1047', Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vo. 78, Part 1 (1988), pp. 132-33

- Geoffrey H. White, 'The First House of Bellême', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fourth Series, Vol. 22 (1940), p. 83

- The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, Ed. Marjorie Chibnall, Volume II (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1993), P. 15

- Violence Against Women in Medieval Texts, Ed. Anna Roberts (University Press of Florida, 1998), p. 49

- Geoffrey H. White, The First House of Bellême, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fourth Series, Vol. 22 (1940), p. 86

- Geoffrey H. White, The First House of Bellême, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fourth Series, Vol. 22 (1940), p. 87

- David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 414

- Elisabeth Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK, 2000), p. 276 & n. 300

- Pauline Stafford, 'Women and the Norman Conquest', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Sixth Series, Vol. 4, (1994), p. 227

- Kathleen Thompson, 'Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Bellême', Journal of Medieval History, Vol. 20 (1994), p. 133

- Kathleen Thompson, 'Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Bellême', Journal of Medieval History, Vol. 20 (1994), p. 134

- Kathleen Thompson, 'Robert of Bellême Reconsidered', Anglo-Norman Studies XIII; Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1990, Ed. Marjorie Chibnall (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1991), p. 280