Battle of Hormozdgan

The Battle of Hormozdgan (also spelled Hormozgan) was the climactic battle between the Arsacid and the Sasanian dynasties that took place on April 28, 224. The Sasanian victory broke the power of the Arsacid dynasty, effectively ending almost five centuries of Parthian rule in Iran, and marking the official start of the Sasanian era.

| Battle of Hormozdgan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

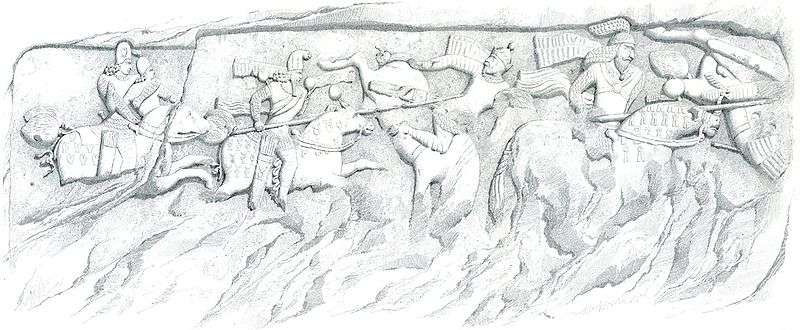

1840 illustration of a Sasanian relief at Firuzabad, showing Ardashir I's victory over Artabanus IV and his forces | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Parthian Empire | Sasanian Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Artabanus IV † Dad-windad |

Ardashir I Prince Shapur (or maybe Farn-Sasan the last Indo-Parthian king)[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| An army larger than Ardashir I's army[2] | 10,000 cavalry[2] | ||||||

Background

Around 208 Vologases VI succeeded his father Vologases V as king of the Arsacid Empire. He ruled as the uncontested king from 208 to 213, but afterwards fell into a dynastic struggle with his brother Artabanus IV,[lower-alpha 1] who by 216 was in control of most of the empire, even being acknowledged as the supreme ruler by the Roman Empire.[3] Artabanus IV soon clashed with the Roman emperor Caracalla, whose forces he managed to contain at Nisibis in 217.[4] Peace was made between the two empires the following year, with the Arsacids keeping most of Mesopotamia.[4] However, Artabanus IV still had to deal with his brother Vologases VI, who continued to mint coins and challenge him.[4] The Sasanian family had meanwhile quickly risen to prominence in their native Pars, and had now under prince Ardashir I begun to conquer the neighboring regions and more far territories, such as Kirman.[3][5] At first, Ardashir I's activities did not alarm Artabanus IV, until later, when the Arsacid king finally chose to confront him.[3]

History

_and_Papak_(right).jpg)

The location of the battle has not been found. The Arabic chronicle Nihayat al-arab states that the battle took place in bʾdrjʾan or bʾdjʾn, which Widengren translated as *Jurbadhijan (Golpayegan).[6] This is however improbable, due to Ardashir I operating around Kashkar before the battle.[6] According to an unfinished work by Bal'ami, the battle took place at Khosh-Hormoz, which is another name for the notable city of Ram-Hormoz, situated near Arrajan and Ahvaz.[6] This implies that Ram-Hormoz was perhaps another word for Hormozdgan, and also clarifies why the latter is not mentioned by Islamic geographers whilst the former is reported in detail.[6] The town of Ram-Hormoz still endures today, and is 65 km east of Ahvaz, "in a wide plain just at the foot of the hills that form the northeastern tail of the Bengestan Mountain of the Zagros chain."[6] According to Shahbazi, "the plain nearby is admirably suited for a cavalry engagement."[6]

According to al-Tabari, whose work was probably based on Sasanian sources,[7] Ardashir I and Artabanus IV agreed to meet in Hormozdgan at the end of the month of Mihr (April).[8] Nonetheless, Ardashir I went to the place before due time to occupy an advantageous spot on the plain.[8] There he dug out a ditch to defend himself and his forces. He also took over a spring at the place.[8] Ardashir I's forces numbered 10,000 cavalry, with some of them wearing flexible chain armor akin to that of the Romans.[6] Artabanus IV led a greater number of soldiers, who, however, were less disposed, due to wearing the inconvenient lamellar armor.[6] Ardashir I's son and heir, Shapur, as portrayed in the Sasanian rock reliefs, also took part in the battle.[9] The battle was fought on 28 April 224, with Artabanus IV being defeated and killed, marking the end of the Arsacid era and the start of 427-years of Sasanian rule.[6]

Aftermath

The chief secretary of the deceased Arsacid king, Dad-windad, was afterwards executed by Ardashir I.[10] Thenceforth, Ardashir I assumed the title of shahanshah ("King of Kings") and started the conquest of an area which would be called Iranshahr (Ērānshahr).[11] He celebrated his victory by having two rock reliefs sculptured at the Sasanian royal city of Ardashir-Khwarrah (present-day Firuzabad) in his homeland, Pars.[12][13] The first relief portrays three scenes of personal fighting; starting from the left, a Persian aristocrat seizing a Parthian soldier; Shapur impaling the Parthian minister Dad-windad with his lance; and Ardashir I ousting Artabanus IV.[13][6] The second relief, conceivably intended to portray the aftermath of the battle, displays the triumphant Ardashir I being given the badge of kingship over a fire shrine from the Zoroastrian supreme god Ahura Mazda, while Shapur and two other princes are watching from behind.[13][12]

Vologases VI was driven out of Mesopotamia by Ardashir I's forces soon after 228.[14][3] The leading Parthian noble-families (known as the Seven Great Houses of Iran) continued to hold power in Iran, now with the Sasanians as their new overlords.[12][7] The early Sasanian army (spah) was identical to the Parthian one.[15] Indeed, the majority of the Sasanian cavalry composed of the very Parthian nobles that had once served the Arsacids.[15] This demonstrates that the Sasanians built up their empire thanks to the support of other Parthian houses, and has due to this has been called "the empire of the Persians and Parthians".[16] However, memories of the Arsacid Empire never completely vanished, with efforts trying to restore the empire in the late 6th-century made by the Parthian dynasts Bahram Chobin and Vistahm, which ultimately proved unsuccessful.[17][18]

- The rock relief of Ardashir I's triumph over Artabanus IV

- Ardashir I receiving the badge of kingship over a fire shrine from the Zoroastrian supreme god Ahura Mazda

Notes

- Artabanus IV is erroneously known in older scholarship as Artabanus V. For further information, see Schippmann (1986a, pp. 647–650)

References

- Kalani 2017: 32,33

- Shahbazi 2003, p. 469–470.

- Schippmann 1986a, pp. 647–650.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 3.

- Schippmann 1986b, pp. 525–536.

- Shahbazi 2004, pp. 469–470.

- Wiesehöfer 1986, pp. 371–376.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 5: p. 13.

- Shahbazi 2002.

- Rajabzadeh 1993, pp. 534–539.

- Daryaee 2014, pp. 2–3.

- Shahbazi 2005.

- McDonough 2013, p. 601.

- Chaumont & Schippmann 1988, pp. 574–580.

- McDonough 2013, p. 603.

- Olbrycht 2016, p. 32.

- Shahbazi 1988, pp. 514–522.

- Shapur Shahbazi 1989, pp. 180–182.

Sources

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.). The History of Al-Ṭabarī. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chaumont, M. L.; Schippmann, K. (1988). "Balāš VI". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 6. pp. 574–580.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 0857716662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kalani, Reza., (2017). Multiple Identification Alternatives for Two Sassanid Equestrians on Fīrūzābād I Relief: A Heraldic Approach, Tarikh Negar Monthly, Tehran. (Google Books)

- McDonough, Scott (2013). "Military and Society in Sasanian Iran". In Campbell, Brian; Tritle, Lawrence A. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Warfare in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–783. ISBN 9780195304657.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2016). "Dynastic Connections in the Arsacid Empire and the Origins of the House of Sāsān". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785702082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rajabzadeh, Hashem (1993). "Dabīr". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 5. pp. 534–539.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schippmann, K. (1986a). "Artabanus (Arsacid kings)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 647–650.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schippmann, K. (1986b). "Arsacids ii. The Arsacid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 525–536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "Hormozdgān". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 469–470.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian Dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2002). "Šāpur I". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1989). "BESṬĀM O BENDŌY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 2. pp. 180–182. Retrieved 13 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1988). "Bahrām VI Čōbīn". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. London et al. pp. 514–522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiesehöfer, Joseph (1986). "Ardašīr I i. History". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 4. pp. 371–376.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Morony, Michael G. (2005) [1984]. Iraq After The Muslim Conquest. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-59333-315-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)