Hoover High School (San Diego)

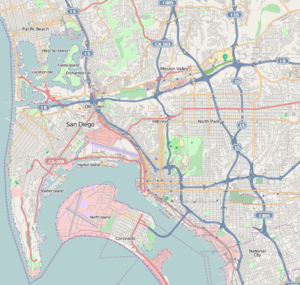

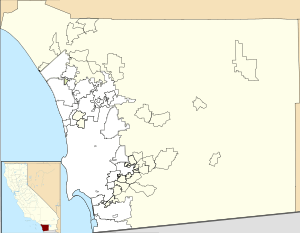

Herbert Hoover High School is a comprehensive, public secondary school located in the City Heights neighborhood of San Diego, California, United States.[2] It is part of the San Diego Unified School District.

| Herbert Hoover High School | |

|---|---|

| Address | |

Herbert Hoover High School  Herbert Hoover High School  Herbert Hoover High School  Herbert Hoover High School | |

4474 El Cajon Blvd. , United States | |

| Coordinates | 32°45′22″N 117°05′53″W |

| Information | |

| Type | Public |

| Opened | 1930 |

| School district | San Diego Unified School District |

| Superintendent | Cindy Marten |

| Principal | Jason Babineau |

| Faculty | 91.67 (FTE)[1] |

| Grades | 9–12 |

| Enrollment | 2,167 (2018–19)[1] |

| Student to teacher ratio | 23.64[1] |

| Color(s) | |

| Mascot | Cardinal |

| Rival | Crawford High School |

| Website | Hoover High School |

%26groups%3D_2be186c50336ff26451d0df10c9a8c9973fd8c80.svg)

| |

It is one of the oldest schools in San Diego.[3]

History

The school was established in 1930 and named in honor of then U.S. President Herbert Hoover. The first principal was Floyd Johnson.[4] It originally opened as a beige stucco building with a red-tile roof and unreinforced concrete, giving it a Spanish-style appearance. As part of a tradition related to signing their yearbooks, 12th grade (senior) students climbed a tower that became a signature defining aspect of the campus.[3]

In 1954 California Concerts (also referred to as Jazz Goes to High School) was a live album by saxophonist and bandleader Gerry Mulligan featuring performances recorded at the Stockton High School in Stockton and Hoover High.

The school underwent renovations in the early 1970s. The tower and other architectural features were erased by the renovation.[3]

As of 2004, Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and Douglas Williams, the authors of Five Years Later, stated that before 1998, Hoover had been known as the "ghetto school" of San Diego USD, and that schools with higher academic performances poached the best students from Hoover.[5] Adam Berman,[6] who previously taught at Hoover,[7] wrote that in 1988 Hoover had low teacher morale, acts of violence, and a high dropout rate in addition to poor academic performance.[6]

The school joined the City Heights Educational Initiative, along with two other high schools and San Diego State University, in 1998 as part of an effort to improve.[8] In 2000 the school met its California state accountability target. This was the first time it had done so in 15 years.[7] Circa 2000 Berman,[6] by then a California Department of Education employee, wrote an independent review of the changes made at Hoover.[7] The review, titled "A focus on literacy: Hoover High School in San Diego," was published in the California High School Newsletter.[6]

Around 2015 the school was scheduled to receive a renovation of the administrative area and main entrance, and parents and community members lobbied for a restoration of the tower and other historic architectural features as part of this renovation. Burt Nestor, a member of the Hoover class of 1946, gave the school a 2-square-foot (0.19 m2) chunk of an ornamental archway from the original building. His son gave it to him as a gift around 1973, as the renovation had destroyed portions of the original campus. The piece is to be either used in the 2015 renovation, or displayed separately.[3]

In 2015 Michael Shefcik, the supervisor of plant operations at Hoover, discovered that a sculpture in the library was actually a 1940 30-inch (760 mm) Works Progress Administration (WPA) statue, titled Girl Reading and created by Donal Hord, depicting a girl reading a book.[9]

Student body

As of 2016 the school had over 2,100 students. The school consists of 73% Hispanic, 10% African American, 10% Indochinese, with Asian at 1.8% and white at 1%.[10] Hoover is a Title 1 school. That status is determined by the number of students who receive free or reduced lunch. 90% of Hoover students qualify for meal eligibility.[10]

The City Heights neighborhood, in the school's attendance area, houses many immigrant families and low income families.[2]

Programs

As of 2015 Hoover High is establishing a wellness center which will offer counseling services as well as some medical services.[2]

Student discipline

In 2013 the school enacted a program in which teachers learn to recognize signs of trauma in students. Suspensions from school were reduced by 80%.[2]

Academic performance

In 1999 the school had a 444/1000 Academic Performance Index (API),[7] the lowest score in San Diego County. It had a statewide rank of the lowest 10% (first decile),[5] and the lowest 20% of schools with similar demographics.[8] The Gates-MacGinitie reading assessments at this school resulted in a 5.9 grade level equivalent for the average student. At that time the school was among the twenty high schools in California with the worst academic performance.[5]

In 2002 it had an API of 506, an increase by 62 points. By 2000 the reading achievement scores had risen by an average of 2.4 years.[7]

Athletics

By the 2010s Hoover High received renovations that improved its football stadium. Artie Ojeda of NBC San Diego stated that it then had "one of the nicer high school stadium facilities in San Diego".[11]

In 2012 the school began holding football games at night. Some residents of Talmadge were unhappy with this, so a legal battle between the school and residents was begun, and night football games stopped in September 2013. In 2014 a judge ruled that the night football games could continue.[11]

Notable alumni

- Tony Banks, former NFL quarterback

- Ben Chase, former NFL player

- Michael Davis, played for Oakland A's and for LA Dodgers 1988 World Series team

- Jerry DaVanon, former MLB infielder[12]

- Bob deLauer, former NFL player

- Bennie Edens, 2002 NFL High School Coach of the Year

- William Gay, former NFL defensive end

- Ted Giannoulas, San Diego Chicken (The Famous Chicken)[3]

- Gene Leek, baseball player for first Los Angeles Angels team

- Bill McColl (born 1930), collegiate All-American and NFL player

- Dave Morehead, former MLB pitcher, Boston Red Sox

- Volney Peters, former NFL defensive tackle

- Robert O. Peterson, founder of the Jack in the Box restaurant chain

- Rick Shaw, former CFL defensive back and wide receiver

- Gina Simmons, psychotherapist and writer

- Willie Steele, Olympic gold medalist

- Burr Van Nostrand (born 1945), avant-garde composer[13]

- Ted Williams, Major League Baseball Hall of Fame, Boston Red Sox[3]

- Eddie Williams, former MLB first and third baseman

- Mickey Wright, pro golfer, member of World Golf Hall of Fame

See also

- Primary and secondary schools in San Diego, California

- List of high schools in San Diego County, California

- List of high schools in California

References

- Fisher, Douglas, Nancy Frey, and Douglas Williams. Five Years Later (Chapter 9). In: Strickland, Dorothy S. and Donna E. Alvermann. Bridging the Literacy Achievement Gap, Grades 4-12 (Language and literacy series). Teachers College Press, January 1, 2004. ISBN 0807744875, 9780807744871. START: p. 147.

Notes

- "Hoover High". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Burks, Megan. "San Diego Campus Builds On School Discipline Reform With Wellness Center." KPBS. Friday August 21, 2015. Retrieved on May 18, 2016.

- Bell, Diane. "Historic chunk of Hoover High reappears" (Archive). San Diego Union-Tribune. July 27, 2015. Retrieved on January 18, 2016.

- North Park Historical Society. San Diego's North Park (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing, September 8, 2014. ISBN 1439647178, 9781439647172. p. 78.

- Douglas, Frey, and Williams, p. 147.

- Douglas, Frey, and Williams, p. 160.

- Douglas, Frey, and Williams, p. 159.

- Douglas, Frey, and Williams, p. 148.

- Bell, Diane. "WPA art is discovered 'hidden in plain sight'" (Archive). San Diego Union-Tribune. October 2, 2015. Retrieved on January 18, 2016.

- Data Analysis and Reporting Department (April 26, 2017). "Grades K to 12 Fall Enrollment Data" (PDF). sandi.net. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- Ojeda, Artie. "Judge: Hoover HS Night Games Can Resume ." NBC San Diego. February 7, 2014. Retrieved on May 18, 2016.

- "Jerry DaVanon Stats". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

High School: Herbert Hoover HS (San Diego, CA)

- American Composers Alliance. "Burr Van Nostrand". Retrieved 25 January 2017.