Hollow-Face illusion

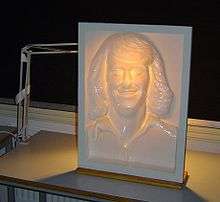

The Hollow-Face illusion (also known as Hollow-Mask illusion) is an optical illusion in which the perception of a concave mask of a face appears as a normal convex face.

While a convex face will appear to look in a single direction, and the gaze of a flat face, such as the Lord Kitchener Wants You poster, can appear to track a moving viewer, a hollow face can appear to move its eyes faster than the viewer: looking forward when the viewer is directly ahead, but looking at an extreme angle when the viewer is only at a moderate angle.

According to Richard Gregory, "The strong visual bias of favouring seeing a hollow mask as a normal convex face is evidence for the power of top-down knowledge for vision".[1] This bias of seeing faces as convex is so strong it counters competing monocular depth cues, such as shading and shadows, and also very considerable unambiguous information from the two eyes signalling stereoscopically that the object is hollow. (Lighting a concave face from below to reverse the shading cues making them closer to those of a convex face lit from above can reinforce the illusion.)

The Hollow-Face illusion has been used to study the dissociation between vision-for-perception and vision-for-action (see Two-streams hypothesis).[2] In this experiment,[3] people used their finger to make a quick flicking movement at a small target attached to the inside surface of the hollow – but apparently normal – face, or on the surface of a normal protruding face. The idea was that the fast flicking (rather like flicking a small insect off the face) would engage the vision-for-action networks in the dorsal stream – and thus would be directed to the actual rather than the perceived position of the target. The results were clear. Despite the presence of a robust illusion in which people perceived the hollow face as if it were a normal protruding face, the flicking movements they made were accurately directed to the real, not the illusory location of the target. This result suggests that the bottom-up cues that drive the flicking response are distinct from the top-down cues that drive the Hollow-Face illusion.

Another example of the Hollow-Face illusion is the "Gathering 4 Gardner" dragon. This dragon's head seems to follow the viewer's eyes everywhere (even up or down), when lighting, perspective and/or stereoscopic cues are not strong enough to tell its face is actually hollow. Keen observers will note that the head doesn't actually follow them, but appears to turn twice as fast around its center than they do themselves.

The Hollow-Face illusion is weaker among people with schizophrenia and other populations with psychotic symptoms, perhaps as a result of reduced tendency to interpret any kind of ambiguous 3D object as convex. It appears to be related to current mental state, namely in regard to current positive symptoms, inappropriate affect, and need for structure.[4][5] The illusion seems to strengthen among successfully treated patients.[6]

Further examples

Hollow-face in snow

Hollow-face in snow An optical illusion. A paper dragon shown from four angles across the 90 degree effective viewing area

An optical illusion. A paper dragon shown from four angles across the 90 degree effective viewing area The back of the paper dragon

The back of the paper dragon

See also

References

- Gregory, Richard (1970). The Intelligent Eye. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Goodale MA, Milner AD (1992). "Separate visual pathways for perception and action". Trends Neurosci. 15 (1): 20–5. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(92)90344-8. PMID 1374953.

- Króliczak G, Heard P, Goodale MA, Gregory RL (2006). "Dissociation of perception and action unmasked by the hollow-face illusion". Brain Res. 1080 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.107. PMID 16516866.

- Emrich HM (1989). "A three-component-system hypothesis of psychosis. Impairment of binocular depth inversion as an indicator of a functional dysequilibrium". British Journal of Psychiatry. 155 (5): S37-39. doi:10.1192/S0007125000295962. PMID 2690888.

- Keane BP, Silverstein SM, Wang Y, Papathomas TV (2013). "Reduced depth inversion illusions in schizophrenia are state-specific and occur for multiple object types and viewing conditions" (PDF). J Abnorm Psychol. 122 (2): 506–12. doi:10.1037/a0032110. PMC 4155576. PMID 23713504.

- Schneider U, Borsutzky M, Seifert J, Leweke FM, Huber TJ, Rollnik JD, et al. (2002). "Reduced binocular depth inversion in schizophrenic patients". Schizophr Res. 53 (1–2): 101–8. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00172-9. PMID 11728843.