Hodotermes

Hodotermes (from Greek ὁδός (hodós), travelling; Latin termes, woodworm) is a genus of African harvester termites in the Hodotermitidae. They range from Palaearctic North Africa, through the East African savannas to the karroid regions of southern Africa.[2][3] As with harvester termites in general, they have serrated inner edges to their mandibles, and all castes have functional compound eyes.[3] They forage for grass at night and during the day, and their pigmented workers[4] are often observed outside the nest.[3]

| Hodotermes | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| H. mossambicus workers cutting dry grass at dusk, and a soldier defending workers at the unobtrusive nest entrance, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Hodotermes Hagen, 1853 |

| Species[1] | |

| |

| |

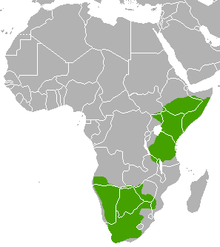

| Core range of H. mossambicus | |

Nests

They nest by excavating in the soil,[3] and the diffuse subterranean system of H. mossambicus may contain several spherical hives which may be 60 cm in diameter. They are interconnected by galleries and are located from near the surface to more than 6 m deep.[3][4] Loose particles of excavated soil are brought to the surface and dumped at various points around the nest.[3]

Diet

The diet of H. mossambicus consists primarily of ripe and/or frost- or drought-killed grass, though tree and shrub material is consumed to a lesser degree. In a stable isotope study of H. mossambicus, the grass component was found to constitute upwards of 94% of their food intake.[5] In this species, the sixth instar larvae digest and distribute food within the colony[5] by means of stomodeal trophallaxis. The mutual feeding also reinforces the colony's integrity, as the feeders discriminate against individuals with unfamiliar intestinal microbiota.[6]

Castes and activity patterns

_(6856939924).jpg)

The foraging worker caste of H. mossambicus consists of two types, named "small" and "large",[7][8] and the larger workers are characterized by very large flattened heads.[9] Soldiers of the genus stay near the nest, and are not known to accompany workers on their expeditions.[9] H. mossambicus is known to exhibit a seasonal cycle in its activities, which involves intensive diurnal winter surface foraging followed by a shift to sporadic nocturnal foraging at the beginning of the rainy season.[10][11][12] With the advent of spring a shift from a diurnal to a nocturnal foraging pattern is evident.[13]

Breeding

Some three to five days after the first major rains,[14] swarms of flying termites, alates (winged reproductives) emerge from their underground nests during summer evenings. When sufficiently distant from the parent nest, they land, shrug off their wings, and scout about for a mate. The pair then excavates a burrow to start a new colony. A week after swarming, the female lays her first eggs, which are tended by the couple, a task soon taken over by the maturing workers. After some four months, the nest is sufficiently developed to send foraging workers to the surface. For the next few years, most of the eggs develop into workers and a small number of soldiers. When the nest is sufficiently large, winged reproductives again develop.[15]

Predators

Harvester termites in general form the main component in the diet of the diurnal bat-eared fox in east and southern Africa.[16] For this unusual diet, these foxes have 48 small teeth compared to the 42 teeth of all other dogs. They also have large ears to hear the insects in their underground chambers, before they are dug up. Though the aardwolf is a specialized predator of certain Trinervitermes, they may assume a partially diurnal habit in winter to obtain harvester termites.[17] The worker castes present the dominant, and seasonally the exclusive food item of some Chondrodactylus, Pachydactylus and Ptenopus gecko species. Ptenopus females especially, seem to gorge on nocturnal foraging congregations in spring to supplement their vitellogenic requirements.[9]

Economic impact

They can deplete grass in pastures and contribute to soil erosion, but are less effective when grasslands are not overgrazed or disturbed.[3][4] Over the long term, however, their decomposing and recycling of plant material contribute to soil fertility and the global cycling of carbon, nitrogen, and other elements.[5]

References

- " Hodotermes Hagen, 1853". Isoptera. biolib.cz. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- Abe, Takuya; et al. (2000–2002). Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-7923-6361-3.

- Scholtz, Clarke H.; et al. (1985). Insects of Southern Africa. Durban: Butterworths. p. 57. ISBN 978-0409-10487-5.

- Picker, Mike; et al. (2004). Field Guide to Insects of South Africa. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-77007-061-5.

- Symes, Craig T.; Woodborne, Stephan (1 April 2011). "Estimation of food composition of Hodotermes mossambicus (Isoptera: Hodotermitidae) based on observations and stable carbon isotope ratios". Insect Science. 18 (2): 175–180. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7917.2010.01344.x.

- Minkley, Nina; et al. "Nestmate discrimination in the harvester termite Hodotermes mossambicus". IUSSI. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Hegh, E. 1922. Les Termites. Imprimerie Industrielle et Financiere, Bruxelles

- Watson, J. A. L. 1973. The worker caste of the hodotermitid harvester termites. Insects Sociaux 20: 1-20

- Bauer, A. M.; Russell, A. P.; Edgar, B. D. (2 October 2015). "Utilization of the termite (Hagen) by gekkonid lizards near Keetmanshoop, South West Africa". South African Journal of Zoology. 24 (4): 239–243. doi:10.1080/02541858.1989.11448159.

- Sands, W. A. 1965. Mound population movements and fluctuations in Trinervitermes ebenerianus Sjöst. (Isoptera, Termitidae, Nasutitermitinae). Insects Sociaux 12: 49-58

- Nel, J. J. C. 1968. Distribution of the foraging holes and soil temperatures of the harvester termite Hodotermes mossambicus (Hagen). S. Afr. J. Agric. Sci. 11: 173-182

- Coaton, W. G. H.; Sheasby, J. L. 1975. National survey of the Isoptera of Southern Africa. 10. The genus Hodotermes Hagen (Hodotermitidae). Cimbebasia, Ser. A. Vol. 3: 105-138

- Coaton, W. G. H. 1958. The hodotermitid harvester termites of South Africa. Dept. Agri. Sci. Bull., S. Afr., Entomol. Ser. 375: 1-112

- Nel, J. J. C.; Hewitt, P. H. 1978. Swarming in the harvester termite Hodotermes mossambicus (Hagen). J. Entom. Soc. South Afr. 41: 195-198

- Bell, R. A. (1999). "Insect Pests: Harvester Termites". Veld in KwaZulu-Natal 11.1. KwaZulu-Natal Department of Agriculture and Environmental Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- Ewer, R. F. (1973). The Carnivores. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 161.

- Holekamp, Kay E.; et al. "Aardwolf: Diet and Foraging". The extant (living) hyaena species. IUCN, Hyaena Specialist Group. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hodotermes. |

- Wolf spider's termite hunt goes wrong, Earth Touch, 2011, YouTube