Thomas Hoccleve

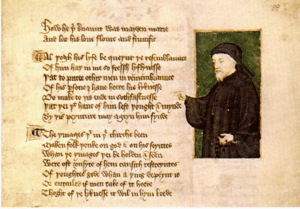

Thomas Hoccleve or Occleve (1368–1426) was an English poet and clerk who has been seen as a key figure in 15th-century Middle English literature.

Biography

Hoccleve was born in 1368, as he states when writing in 1421 (Dialogue, 1.246) that he has seen "fifty wyntir and three".[1] Nothing is known of his family, but they probably came from the village of Hockliffe in Bedfordshire.[2] In November 1420, Hoccleve's fellow Privy Seal clerk John Bailey returned land and tenements in Hockliffe to him, suggesting that Hoccleve may indeed have had family ties there.[3]

What is known of his life comes mainly from his works and from administrative records. He obtained a clerkship in the Office of the Privy Seal at the age of about twenty.[4] This would require him to know French and Latin. He retained the post on and off for about 35 years, despite grumbling. He had hoped for a church benefice, but none came. However, on 12 November 1399 he was granted an annuity by the new king, Henry IV.[5] The Letter to Cupid, the first datable poem of his was a 1402 translation of L'Epistre au Dieu d'Amours of Christine de Pisan, written as a sort of riposte to the moral of Troilus and Criseyde, to some manuscripts of which it is attached. La Male Regle (c. 1406), one of his most fluid and lively works, is a mock-penitential poem that gives some glimpses of dissipation in his youth.

By 1410 he had married "only for love" (Regiment..., 1.1561) and settled down to writing moral and religious poems. He was still married in November 1420 when he and his wife receive bequests in a will.[6] His best-known Regement of Princes or De Regimine Principum, written for Henry V of England shortly before his accession, is a homily on virtues and vices, adapted from Aegidius de Colonna's work of the same name, from a supposed epistle of Aristotle known as Secretum Secretorum, and a work of Jacques de Cessoles (fl. 1300) translated later by Caxton as The Game and Playe of Chesse. The Regement survives in at least 43 manuscript copies.[7] It comments on Henry V's lineage, to cement the House of Lancaster's claim to England's throne. Its incipit is a poem occupying about a third of the whole, containing further reminiscences of London tavern life in a dialogue between the poet and an old man. He also remonstrated with Sir John Oldcastle, a leading Lollard, calling on him to "rise up, a manly knight, out of the slough of heresy."

The Series, which combines autobiographical poetry, poetic translations and prose moralizations of the translated texts, begins with a description of a period of "wylde infirmitee". in which the Hoccleve-character claims he temporarily lost his "wit" and "memorie" (this stands as the earliest autobiographical description of mental illness in English).[8] He describes recovering from this "five years ago last All Saints" (Complaint, 11.55–6) but still experiencing social alienation as a result of gossip about this insanity.[7] The Series continues with "Dialog with a Friend," which claims to be written after his recovery and gives a pathetic picture of a poor poet, now 53, with sight and mind impaired. In it he tells the unnamed friend of his plans to write a tale he owes to his good patron, Humphrey of Gloucester, and of translating a portion of Henry Suso's popular Latin treatise on the art of dying – a task the friend discourages, pointing out that too much study was the cause of his mental illness.[9] The Series then fulfils this plan, continuing with his moralized tales of Jereslau's Wife and of Jonathas (both from the Gesta Romanorum). The Series next turns to Learn to die, a theologically and psychologically astute verse translation of Henry Suso's Latin prose Ars Moriendi (Book II, Chapter 2 of the Horologium Sapientiae).[10] The theme of mortality and strict calendar structure of the Series link this sequence of poems to the death of Hoccleve's friend and Privy Seal colleague John Bailey in November 1420.[11] This motivation is supported by the revised date of the Series - November 1420 to All Saints (1 November) 1421 - bringing forward the date of his mental illness to 1415.[12] Two autograph manuscripts of the Series survive.[13]

In addition to writing his own poetry, Hoccleve seems to have supplemented the income from his Privy Seal clerkship by working as a scribe. He was "Scribe E" on a manuscript of John Gower's Confessio Amantis, which also features "Scribe B", copyist of the Hengwrt_Chaucer and Ellesmere_Chaucer manuscripts, and the prolific copyist "Scribe D".[14] He also compiled a formulary of more than a thousand model Privy Seal documents in French and Latin for the use of other clerks.[15]

On 4 March 1426 the Exchequer issue rolls record a last reimbursement to Hoccleve (for red wax and ink for office use). He died soon after. On 8 May 1426 his corrody at Southwick Priory was granted to Alice Penfold to be held "in manner and form like Thomas Hoccleve now deceased".[7]

Work

Like his more prolific, better known contemporary John Lydgate, Hoccleve is a key figure in 15th-century English literature. For much of the 20th century his work was little valued, but it is now seen as offering great insight into the literate culture of England under the Lancastrian regime. It represented for the 15th century the literature of their time, keeping alive the innovations to vernacular poetics originally made by their "maister" Geoffrey Chaucer, to whom Hoccleve pays affectionate tribute in three passages in his De Regimine Principum. Hoccleve's first work for which a certain date is known is "Letter of Cupid" (1402).[16]

The main interest in Hoccleve's poems today is for portraying the character of his time. His hymns to the Virgin, ballades to patrons, complaints to the king and the kings treasurer, versified homilies and moral tales, with warnings to heretics like Oldcastle, illustrate the blight that had fallen upon poetry with Chaucer's death. The nearest approach to the realistic touch of his master occurs in Hoccleve's Male Regle. Compared to Lydgate and his humorous "London Lickpenny", these pictures of 15th-century London are more serious, as they ruminate on a civil servant's place in an unstable Lancastrian bureaucracy.

Yet Hoccleve claimed to know the limits of his powers. His diction is relatively simple and straightforward, and as a metrist he is highly self-deprecating. While he confesses that "Fader Chaucer fayn wolde han me taught, But I was dul and learned lite or naught," this pose was conventional in 15th-century poetry and an inheritance from Chaucer himself, whose alter-ego Geoffrey was portrayed as fat and dimwitted in both the "House of Fame" and The Canterbury Tales. Later known as the "humility topos", this posture would become a conventional form of authorial self-presentation in the Renaissance.[17]

The scansion of his verses seems occasionally to call in French fashion for an accent on an unstressed syllable. Yet the seven-line rhyme royal and eight-line stanzas to which he limited himself are perhaps more reminiscent of Chaucer's rhythm than Lydgate's.

The Oxford English Dictionary cites Hoccleve as one of the initial users of the term "slut" in its modern sense, though not in its modern spelling.

A poem, Ad beatam Virginem, generally known as Mother of God and once attributed to Chaucer, is copied among Hoccleve's works in manuscript in Phillipps 8151 (Cheltenham), and so may be regarded as his work. Hoccleve found an admirer in the 17th century in William Browne, who included his Jonathas in Shepheard's Pipe (1614). Browne added a eulogy of the poet, whose works he intended to publish in their entirety (Works, ed. WC Hazlitt, 1869, ii. f 96-198). In 1796 George Mason printed Six Poems by Thomas Hoccleve never before printed ...; De Regimine Principum was printed for the Roxburghe Club in 1860, and by the Early English Text Society in 1897. (See Frederick James Furnivall's introduction to Hoccleve's Works; I. The Minor Poems, in the Phillipps manuscript 8131, and the Durham manuscript III. p, Early English Text Society, 1892.)

Editions

Furnivall's edition of Hoccleve's complete works, still largely standard in current scholarship, was reprinted in the 1970s, though Michael Seymour's Selections from Hoccleve, published by Clarendon Press (a division of Oxford U.P.) in 1981, provides an excellent sampling of the poet's major and minor works for readers trying to get the sense of Hoccleve's work. J. A. Burrow's 1999 EETS edition of Thomas Hoccleve's Complaint and Dialogue is becoming the standard edition of these two excerpts from the Hoccleve's later works (now collectively known as The Series), as is Charles Blyth's TEAMS Middle English Text Series edition of The Regiment of Princes from the same year – particularly for its modernised spelling, which makes it easier to use in the classroom. These three recent editions all contain introductions offering a thorough sense of a poet hitherto under-appreciated.

Scholarship

- Knapp, Ethan. The Bureaucratic Muse: Thomas Hoccleve and the Literature of Late Medieval England, Penn State Press, 2001 ISBN 0-271-02135-7

- Perkins, Nicholas (2001), Hoccleve's Regiment of Princes: Counsel and Constraint, Boydell & Brewer

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2019), Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author, Oxford University Press ISBN 9780198790785, Chapter 2, 'The Series: Hoccleve's Year of Mourning', pp. 65-100.

- Watt, David (2013), The Making of Thomas Hoccleve's 'Series'

References

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2019). Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author in Late Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780198790785.

- J. A. Burrow: Hoccleve, Thomas...: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: OUP, 2004; online ed., January 2008 Retrieved 24 November 2010. Subscription required.

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2019). Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author in Late Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 65–73. ISBN 9780198790785.

- He remarks in the Regiment of Princes (c. 1411, 11.804–5) that he has been writing for the seal "xxti year and iiij, come Estren" (quoted by A. Burrow: Hoccleve, Thomas....)

- £10 per annum, raised to 20 marks (£13 6s. 8d.) in 1409, the last half-yearly payment being made on 11 February 1426. His fringe benefits included board and lodging, money for robes at Christmas, two corrodies, occasional bonuses, and fees and favours from clients. A Burrow: Hoccleve, Thomas....

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2019). Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author in Late Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 9780198790785.

- A. Burrow: Hoccleve, Thomas.

- (Complaint, 11.40 ff.)

- Kinch, Ashby (2013), Imago Mortis: Mediating Images of Death in Late Medieval Culture, Brill

- Rozenski, Steven (2008), "'Your Ensaumple and Your Mirour': Hoccleve's Amplification of the Imagery and Intimacy of Henry Suso's Ars Moriendi", Parergon, 25: 1–16

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2019). Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author in Late Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–100. ISBN 9780198790785.

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2019). Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author in Late Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 74–87. ISBN 9780198790785.

- Burrow, J. A., ed. (2002), Thomas Hoccleve: A Facsimile of the Autograph Verse Manuscripts, ISBN 9780197224205

- A. I. Doyle and M. B. Parkes, "The Production of Copies of the Canterbury Tales and the Confessio Amantis in the Early Fifteenth Century", in Medieval Scribes, Manuscripts and Libraries: Essays Presented to N. R. Ker, ed. M. B. Parkes and Andrew G. Watson (London: Scolar Press, 1978), pp. 163–210.

- BL, Add. MS 24062.

- Medium Ævum, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1971 Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- The seminal study of this self-effacing performance typical of 15th-century writers is David Lawton's 1987 ELH article "Dullness and the Fifteenth Century".

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Hoccleve |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas Hoccleve |

- The International Hoccleve Society: Devoted to promoting scholarship on the late-medieval poet Thomas Hoccleve

- The Hoccleve Archive: Resources for Scholars, Teachers, and Students interested in Thomas Hoccleve, his Works, and their Textual History

- MS 1083/30 Regiment of princes; Consolation of philosophy at OPenn

- The Regiment of Princes,, edited by Charles R. Blyth. TEAMS, Middle English Text Series

- Hoccleve's short poetry, edited by Frederick J. Furnivall and I. Gollancz based on his holograph manuscripts

- Works by or about Thomas Hoccleve at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Hoccleve at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)