Hoa Hakananai'a

Hoa Hakananai'a is a moai (Easter Island statue) housed in the British Museum in London. It was taken from Orongo, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) in November 1868 by the crew of the British ship HMS Topaze,[1] and arrived in England in August 1869.[2] Though relatively small, it is considered to be typical of the island's statue form,[3][4] but distinguished by carvings added to the back, associated with the island's birdman cult.[5] It has been described as a "masterpiece"[6] and "without a doubt, the finest example of Easter Island sculpture".[7]

| Easter Island Statue | |

|---|---|

Hoa Hakananai'a in the Wellcome Gallery. | |

| Material | Flow lava |

| Size | Height: 2.42 metres (7.9 ft) |

| Created | c. 1000-1600 AD |

| Present location | British Museum, London, Gallery 24 |

| Registration | 1869,1005.1 |

Etymology

The statue was identified as Hoa Hakananai'a by islanders at the time it was removed, the British crew first recording the name in the form Hoa-haka-nana-ia or Hoa-haka-nama-ia.[8] It has been variously translated from the Rapa Nui language to mean breaking wave,[9] surfriding,[8] surfing fellow[10][11] or master wave-breaker;[12] and lost or stolen friend,[13] stolen friend or hidden friend[14] or doing robberies/mockeries friend.[10]

Provenance

When recorded in 1868, Hoa Hakananai'a was standing erect, part buried inside a freestone ceremonial "house" in the Orongo village at the south-western tip of the island. It faced towards an extinct volcanic crater known as Rano Kau, with its back turned to the sea.[15][16] It may have been made for this location, or first erected elsewhere before being moved to where it was found.[16][17]

Description

Most statues on Easter Island are of a reddish tuff,[18][19] but Hoa Hakananai'a is made from a block of dark grey-brown flow lava.[20] Though commonly described as basalt, quarried near to where the statue was found,[19] there is no record of petrological analysis to confirm this.[21][22] It stands 2.42 metres (7.9 feet) high, is 96 cm (3.15 ft) across, and weighs 4.2 tonnes.[13]

The base of the statue, now concealed in a modern plinth, may originally have been flat, and subsequently narrowed, or was rough and tapering from the start.[23][24][25]

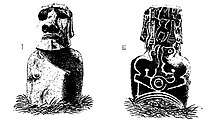

Typical of Easter Island moai, Hoa Hakananai'a features a heavy brow, blocky face with prominent nose and jutting chin, nipples, thin, lightly angled arms down the sides and hands reaching towards the stomach, which is near the base. It has a raised Y-shape in the centre of the chin, eyes hollowed out in a way characteristic of statues erected elsewhere on the island on ceremonial ahu platforms, and long, rectangular stylised ears. A line around the base of the neck is interpreted as representing the clavicles;[23][24][25] there is a semi-circular hollow for the suprasternal notch.

The front of Hoa Hakananai'a's Head

The front of Hoa Hakananai'a's Head Damage on Hoa Hakananai'a's hands at the front

Damage on Hoa Hakananai'a's hands at the front

In its original form, the back is thought to have been plain, apart from a maro, a belt or girdle, which consists of three raised lines and a circle above, and an M on a vertical line below. Near the base are slight indications of buttocks.[25]

Lower Back of Hoa Hakananai'a showing the maro, belt or girdle, and buttocks

Lower Back of Hoa Hakananai'a showing the maro, belt or girdle, and buttocks

The top of the head is smooth and flat,[22] and could originally have supported a pukao, a cylindrical stone "hat". A flat round stone found near the site of the statue may have been such a hat,[26] or, if the base was flat, a bed plate on which the statue once stood.[27] It has been suggested that the statue was originally erected so that the top of the head would have been horizontal.[28]

Date

No Easter Island statues have been scientifically dated, but statue making in general is said to have begun by at least 1000 AD,[29] and occurred mostly between 1300 and 1500 AD.[30] Manufacture is said to have ended by 1600 AD, when islanders began to topple them.[31]

Episode 70 of the 2010 BBC Radio 4 series A History of the World in 100 Objects describes the statue as being from 1000-1200 AD.

The Y on the chin and the clavicles are rare on Easter Island statues, and said to be late innovations.[32]

Carvings

The back of the statue, between the maro and the top of the head, is covered with relief carvings added at an unknown time after the statue was made.[5][33][34] They are similar in style to petroglyphs on the native rock around the Orongo village, where they are more common than anywhere else on the island.[35][36]

Either side and above the ring on the maro are two facing birdmen (tangata manu), stylised human figures with beaked heads said to represent frigatebirds. Above these, in the centre of the statue's head, is a smaller bird said to be a sooty tern (manutara). Either side of this is a ceremonial dance paddle (ao), a symbol of male power and prestige. Along the edge of the left ear is a third paddle, because of its smaller size possibly a rapa rather than an ao, and on the right ear a row of four vulva symbols (komari). Y-shaped lines drop down from the top of the head.[37][38]

When first seen by Europeans, the carvings were painted red against a white background. The paint was totally or mostly washed off when the statue was rafted out to HMS Topaze.[39][40]

Precise reading of these designs varies. The birdmen are popularly interpreted as Makemake, a fertility god and chief god of the birdman cult.[41] This cult, said to have replaced the older statue cult, was recorded by early European visitors.[42]

It involved an annual competition to retrieve the first egg laid by migrating sooty terns. The contest was held at Orongo, and the winning man became Makemake's representative for the following year.[43][44] The last ceremony is thought to have been held in 1866 or 1867.[45]

New studies

After the most intensive survey of the statue to date, a more detailed interpretation of the carvings has been proposed.[46] The new survey, which followed an as yet unpublished laser scan survey,[47] comprised a combination of Photogrammetry and Reflectance Transformation Imaging, used to create high-resolution digital images in "two and a half" and three dimensions.[48][49][50]

This allowed several details to be clarified. The Y-shaped lines at the top of the head are the remnants of two large komari, partly removed by the other carvings, which were added at a later date. The small bird has a closed beak, not open as had often been described, and the foot of the left birdman has five toes, not six. There is a small, shallow carving below the left ear, which could be a komari or the head of an ao. The beak of the right birdman comes to a short, rounded end, not a long pointed tip; the latter reading of the digital models was supported by a new interpretation of a photo of the statue taken in 1868.[40]

Petroglyphs on the back of Hoa Hakananai'a

Petroglyphs on the back of Hoa Hakananai'a

The short beak has been contested,[51][52] and in turn the original study has been defended.[53] In other studies, it has been proposed that the existing carvings on the back all but conceal four earlier birdman figures,[54] and that an engraved birdman fills the area of the front between the nipples and the hands.[55] The latter was rejected,[56] and defended.[57] None of this can be seen in the new digital models.[58]

The archaeologists behind the new digital study also proposed a new way to read the main composition. It was suggested that the elements worked together to portray the birdman ceremony, with the left birdman figure male, the right female (two of the four "egg gods"), and the bird above them their new-hatched fledgling. "Meanwhile the entire statue has become Makemake, its face painted white… in the manner of the human birdman".[59] One group of critics described this interpretation as "interesting, thought provoking and even somewhat poetic", but, while "greatly impressed by the work", rejected the proposals.[52]

Close up of the carvings identifying the male (left) and female (right) birdman, with their fledgling above, as proposed in a disputed interpretation. Also seen in this image are the two large earlier komari that extend onto the top of the statue's head

Close up of the carvings identifying the male (left) and female (right) birdman, with their fledgling above, as proposed in a disputed interpretation. Also seen in this image are the two large earlier komari that extend onto the top of the statue's head

Online viewers

The archaeologists behind the new digital study have released online viewers of the Photogrammetry model captured and the Reflectance Transformation Imaging datasets. The latter represent the front,lower back, middle back, upper back and the back of the head. These viewers allow for the dissemination of the results to stimulate discussion.

Recent history

Hoa Hakananai'a was found in November 1868 by officers and crew from the British Royal Navy ship HMS Topaze.[60] When first seen, it was buried up to about half its height or even more.[26][61][62] It was dug out, dragged down from Rano Kau on a sledge, and rafted out to the ship.[1]

It was photographed while Topaze was docked in Valparaiso, Chile, from back[40] and front.[63] At that time Commodore Richard Ashmore Powell,[13] captain of the Topaze, wrote to the British Admiralty offering the statue, along with a second, smaller moai known as Hava.[2]

HMS Topaze arrived in Plymouth, England, on 16 August 1869. The Admiralty offered the statue to Queen Victoria, who proposed that it should be given to the British Museum.[2] It was mounted in a plinth and exhibited outside the museum's front entrance, beneath the portico. During the Second World War, it was taken inside, where it mostly remained until 1966. In that year it was moved to the museum's then Department of Ethnography, which had separate premises in Burlington Gardens. It returned to the British Museum's main site in 2000, when it was exhibited on a new, higher plinth in the Great Court, before moving to its present location in the Wellcome Trust Gallery (Room 24: Living and Dying).[64][65]

Hoa Hakananai'a was selected by British Museum director Neil MacGregor as one of the 100 objects with which he told the history of the world.[66][67]

In 2010 it was the target of a protest against BP's handling of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.[68]

The Rapa Nui people consider that the moai was taken without permission. In November 2018 Laura Alarcón Rapu, the Governor of Easter Island, asked the British Museum to return the statue. The museum agreed to discuss a loan of the statue with representatives of the people.[69] Keeper of the Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas at the British Museum, Lissant Bolton, visited Easter Island in June 2019.[70]

In popular culture

- Hoa Hakananai'a has inspired artists, among them Henri Gaudier-Brzeska[71] and Henry Moore, who was filmed talking about the statue in 1958.[72] Moore commented on its "tremendous presence", and that its makers "knew instinctively that a sculpture designed for the open air had to be big".[73] Ron Mueck exhibited his Mask II in front of Hoa Hakananai'a in 2008/09.[74]

- Robert Frost wrote a poem about it called "The Bad Island – Easter".[75]

- The English artist Ronald Lampitt used it as a model for an illustration of Easter Island for Look and Learn magazine.[76]

- A set of six postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail in 2003 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the British Museum featured Hoa Hakananai'a alongside other Museum objects such as the Sutton Hoo helmet and a mask of Xiuhtecuhtli.[77][78]

References

- Van Tilburg 2006, p. 37.

- Van Tilburg 2006, p. 3.

- Routledge, K (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island. London: Sifton, Praed & Co. p. 166.

- Van Tilburg 2004, pp. 45–47.

- Van Tilburg 1992, pp. 56–59.

- Métraux, A (1940). The Ethnology of Easter Island. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum. p. 298.

- Métraux, A (1957). Easter Island: A Stone-Age Civilisation of the Pacific. London: Andre Deutsch. p. 162.

- Van Tilburg 1992, p. 41.

- Routledge, K (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island. London: Sifton, Praed & Co. p. 257.

- Davletshin 2012, pp. 62–63.

- Davletshin, A (2012). "Images, which are not seen, and stolen friends, who steal: A reply to Van Tilburg and Arévalo Pakarati". Rapa Nui Journal. 26 (1): 68.

- "RapaNui Sprache - Übersetzung Buchstabe N". Osterinsel.

- "Hoa Hakananai'a ('lost or stolen friend') / Moai (ancestor figure)". British Museum.

- Van Tilburg 1992, pp. 41–42.

- Routledge, K (1920). "Survey of the village and carved rocks of Orongo, Easter Island, by the Mana Expedition". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 50: 425–45. doi:10.2307/2843492. JSTOR 2843492.

- Van Tilburg 1992, p. 47.

- Pitts et al. 2014, pp. 7–10.

- Van Tilburg, J (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. London: British Museum.

- Van Tilburg 2004, p. 45.

- Pitts et al. 2014, p. 3.

- Van Tilburg, J; Pakarati, C (2012). "Hoa Hakananai'a in detail: comment on A. Davletshin's unconvincing assertion of an "overlooked image" on the ventral side of the 'Orongo statue now in the British Museum". Rapa Nui Journal. 26: 64.

- Pitts et al. 2014, p. 6.

- Van Tilburg 1992, pp. 48–50.

- Van Tilburg 2006, p. 17.

- Pitts et al. 2014, pp. 6–7.

- Pitts et al. 2014, p. 23.

- Routledge, K (1920). "Survey of the village and carved rocks of 'Orongo, Easter Island, by the Mana Expedition". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 50: 436. doi:10.2307/2843492. JSTOR 2843492.

- Pitts et al. 2014, pp. 10–11.

- Van Tilburg 2004, p. 39.

- Fischer, S (2005). The Island at the End of the World. London: Reaktion Books. p. 33.

- "Hoa Hakananai'a Easter Island statue". BBC.

- Van Tilburg 2004, p. 47.

- Van Tilburg 2006, p. 38–40.

- Pitts et al. 2014, pp. 11–19.

- Lee, G (1992). Rock Art of Easter Island: Symbols of Power, Prayers to the Gods. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

- Horley, P; Lee, G (2009). "Painted and carved house embellishments at 'Orongo village, Easter Island". Rapa Nui Journal. 23 (2): 106–24.

- Van Tilburg 2004, pp. 50–51.

- Van Tilburg 2006, p. 38.

- Horley, P; Lee, G (2008). "Rock art of the sacred precinct at Mata Ngarau, 'Orongo". Rapa Nui Journal. 22 (2): 112–14.

- Pitts 2014, pp. 39–48.

- Van Tilburg 2004, p. 22.

- Routledge, K (1917). "The bird cult of Easter Island". Folk-Lore. 28 (4): 335–55. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1917.9719006.

- Flenley, J; Bahn, P (2003). The Enigmas of Easter Island. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 175–77.

- Van Tilburg 2004, p. 23–25.

- Routledge, K (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island. London: Sifton, Praed & Co. pp. 265–66.

- Pitts et al. 2014, pp. 1–31.

- Van Tilburg, J. "Hoa Hakananai'a laser scan project".

- Miles et al. 2014, pp. 596–605.

- Pitts, M; Miles, J; Pagi, H; Earl, G (2013). "Taking flight: the story of Hoa Hakananai'a". British Archaeology. 130: 24–31.

- Pitts, M. "Last night in the Wellcome Gallery".

- Van Tilburg, J (2014). "Comment on M. Pitts' Hoa Hakananai'a, an Easter Island statue now in the British Museum, photographed in 1868'". Rapa Nui Journal. 28: 49–52.

- Lee, G; Horley, P; Bahn, P (2014). "Comments on historical images of the moai Hoa Hakananai'a". Rapa Nui Journal. 28: 53–59.

- Miles, J. "Update on the Hoa Hakananai'a statue".

- Horley, P; Lee, G (2008). "Rock art of the sacred precinct at Mata Ngarau, 'Orongo". Rapa Nui Journal. 22 (2): 112–13.

- Davletshin 2012, pp. 57–63.

- Van Tilburg, J; Pakarati, C (2012). "Hoa Hakananai'a in detail: comment on A. Davletshin's unconvincing assertion of an "overlooked image" on the ventral side of the 'Orongo statue now in the British Museum". Rapa Nui Journal. 26: 64–66.

- Davletshin, A (2012). "Images, which are not seen, and stolen friends, who steal: A reply to Van Tilburg and Arévalo Pakarati". Rapa Nui Journal. 26 (1): 67–68.

- Pitts et al. 2014, p. 11.

- Pitts et al. 2014, pp. 26–28.

- Van Tilburg 2006, pp. 26–37.

- Lee, G; Horley, P; Bahn, P (2014). "Comments on historical images of the moai Hoa Hakananai'a". Rapa Nui Journal. 28: 54–55.

- Horley, P; Lee, G (2008). "Rock art of the sacred precinct at Mata Ngarau, 'Orongo". Rapa Nui Journal. 22 (2): 113–14.

- Lee, G; Horley, P; Bahn, P (2014). "Comments on historical images of the moai Hoa Hakananai'a". Rapa Nui Journal. 28: 56–57.

- Wilson, D (2002). The British Museum: A History. London: British Museum.

- Van Tilburg 1992, p. 4–5.

- MacGregor, N (2010). A History of the World in 100 Objects. London: Allen Lane. pp. 449–55.

- "Hoa Hakananai'a Easter Island statue".

- BBC. "'Oil slick' protest against BP at the British Museum".

- "Easter Island governor begs British Museum to return Moai: 'You have our soul'". The Guardian. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Bartlett, John (4 June 2019). "Easter Islanders call for return of statue from British Museum". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Wilson, D (2002). The British Museum: A History. London: British Museum. p. 226.

- Wyver, J (2013). "Lost encounter". Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Moore, H; Finn, D (1981). Henry Moore at the British Museum. London: British Museum.

- "Ron Mueck".

- Fagan, D (2007). Critical Companion to Robert Frost. New York: Facts on File. pp. 37–38.

- "Ronald Lampitt Archive".

- CollectGBStamps.

- Daily Mail 2003.

Bibliography

- "250th Anniversary of the British Museum". CollectGBStamp. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Davletshin, Albert (May 2012). "An overlooked image on the Hoa-haka-nana'ia stone statue from Easter Island in the British Museum" (PDF). Rapa Nui Journal. Easter Island Foundation. 26 (1): 57–63. Retrieved 20 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Georgia; Horley, Paul & Bahn, Paul (May 2014). "Comments on historical images of the moai Hoa Hakananai'a" (PDF). Rapa Nui Journal. Easter Island Foundation. 28 (1): 53–59. Retrieved 20 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miles, James; Pitts, Mike; Pagi, Hembo & Earl, Graeme (June 2014). "New applications of photogrammetry and reflectance transformation imaging to an Easter Island statue". Antiquity. 88 (340): 596–605. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00101206.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pitts, Mike (May 2014a). "Hoa Hakananai'a, an Easter Island statue now in the British Museum, photographed in 1868" (PDF). Rapa Nui Journal. Easter Island Foundation. 28 (1): 39–48. Retrieved 20 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pitts, Mike (October 2014b). "More on Hoa Hakananai'a: Paint, petroglyphs, and a sledge, and the independent value of archaeological and historical evidence" (PDF). Rapa Nui Journal. Easter Island Foundation. 28 (2): 49–54. Retrieved 20 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pitts, M., Miles, J., Pagi, H. and Earl, G. (2013). "Taking flight: the story of Hoa Hakananai’a". British Archaeology 130: 24–31.

- Pitts, Mike; Miles, Jason; Pagi, Hembo & Earl, Graeme (September 2014). "Hoa Hakananai'a: A new study of an Easter Island statue in the British Museum". The Antiquaries Journal. 94: 291–321. doi:10.1017/S0003581514000201.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Stamps mark 250 years of museum". Daily Mail. London. 6 October 2003. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (1992). HMS Topaze on Easter Island: Hoa Hakananai'a and Five Other Museum Sculptures in Archaeological Context. Occasional Papers. 73. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0861590735.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (2004). Hoa Hakananai'a. Objects in Focus. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0714150246.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (2006). Remote Possibilities: Hoa Hakananai'a and HMS Topaze on Rapa Nui. British Museum Research Papers. 158. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0861591589.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hoa Hakananai'a. |

| Preceded by 69: Statue of Tlazolteotl |

A History of the World in 100 Objects Object 70 |

Succeeded by 71: Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent |