History of origami

The history of origami followed after the invention of paper and was a result of paper's use in society. Independent paper folding traditions exist in East Asia, and it is unclear whether they evolved separately or had a common source.

Origins and the traditional designs

The Japanese word "origami" itself is a compound of two smaller Japanese words: "ori" (root verb "oru"), meaning to fold, and "kami", meaning paper. Until recently, not all forms of paper folding were grouped under the word origami. Before that, paper folding for play was known by a variety of names, including "orikata", "orisue", "orimono", "tatamigami" and others. Exactly why "origami" became the common name is not known; it has been suggested that the word was adopted in kindergartens because the written characters were easier for young children to write. Another theory is that the word "origami" was a direct translation of the German word "Papierfalten", brought into Japan with the Kindergarten Movement around 1880.

Japanese origami began sometime after Buddhist monks carried paper to Japan during the 6th century.[1] The first Japanese origami dates from this period and was used for religious ceremonial purposes only, due to the high price of paper.[2]

A reference in a poem by Ihara Saikaku from 1680 describes the origami butterflies used during Shinto weddings to represent the bride and groom.[3] Samurai warriors are known to have exchanged gifts adorned with noshi, a sort of good luck token made of folded strips of paper, which indicates that origami had become a significant aspect of Japanese ceremony by the Heian period (794–1185).

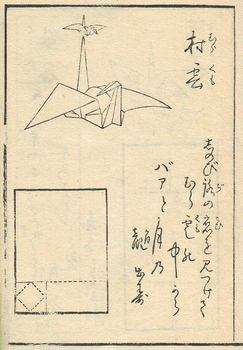

In 1797 the first known origami book was published in Japan: Senbazuru orikata. There are several origami stories in Japanese culture, such as a story of no Seimei making a paper bird and turning it into a real one.[4]

The earliest evidence of paperfolding in Europe is a picture of a small paper boat in the 1498 French edition of Johannes de Sacrobosco's Tractatus de Sphaera Mundi.[5] There is also evidence of a cut and folded paper box from 1440.[6] It is possible that paperfolding in the west originated with the Moors much earlier; however, it is not known if it was independently discovered or knowledge of origami came along the silk route.

The modern growth of interest in origami dates to the design in 1954 by Akira Yoshizawa of a notation to indicate how to fold origami models.[7] The Yoshizawa-Randlett system is now used internationally. Today the popularity of origami has given rise to origami societies such as the British Origami Society and OrigamiUSA. The first known origami social group was founded in Zaragoza, Spain during the 1940s.[8]

The Chinese word for paper folding is "Zhe Zhi" (摺紙), and some Chinese contend that origami is a historical derivative of Chinese paperfolding.

Modern designs and innovations

Friedrich Fröbel, inventor of the kindergartens, recognized paper binding, weaving, folding, and cutting as teaching aids for child development during the early 19th century. As the kindergarten system spread throughout Europe and into the rest of the world, it brought with it the small colored squares that we know of today as origami paper. Josef Albers, the father of modern color theory and minimalistic art, taught origami and paper folding in the 1920s and 30s at the famous Bauhaus design school. His methods, which involved sheets of round paper that were folded into spirals and curved shapes, have influenced modern origami artists like Kunihiko Kasahara.

The work of Akira Yoshizawa, of Japan, a creator of origami designs and a writer of books on origami, inspired a modern renaissance of the craft. He invented the process and techniques of wet-folding and set down the initial set of symbols for the standard Yoshizawa-Randlett system that Robert Harbin and Samuel Randlett later improved upon. His work was promoted through the studies of Gershon Legman as published in the seminal books of Robert Harbin's Paper Magic and more so in Secrets of the Origami Masters which revealed the wide world of paper folding in the mid-1960s.

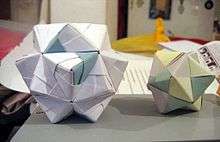

Modern origami has attracted a worldwide following, with ever more intricate designs and new techniques. One of these techniques is 'wet-folding,' the practice of dampening the paper somewhat during folding to allow the finished product to hold shape better. Variations such as modular origami, also known as unit origami, is a process where many origami units are assembled to form an often decorative whole.

Complex origami models normally require thin, strong paper or tissue foil for successful folding; these lightweight materials allow for more layers before the model becomes impractically thick. Modern origami has broken free from the traditional linear construction techniques of the past, and models are now frequently wet-folded or constructed from materials other than paper and foil. With popularity, a new generation of origami creators has experimented with crinkling techniques and smooth-flowing designs used in creating realistic masks, animals, and other traditional artistic themes.

Sadako and the thousand cranes

One of the most famous origami designs is the Japanese crane. The crane is auspicious in Japanese culture. Legend says that anyone who folds one thousand paper cranes will have their heart's desire come true. The origami crane (折鶴 orizuru in Japanese) has become a symbol of peace because of this belief and because of a young Japanese girl named Sadako Sasaki. Sadako was exposed to the radiation of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima as an infant, and it took its inevitable toll on her health. She was then a hibakusha – an atom bomb survivor. By the time she was twelve in 1955, she was dying of leukemia. Her classmate told her about the legend, so she decided to fold one thousand origami cranes so that she could live. However, when she saw that the other children in her ward were dying, she realized that she would not survive and wished instead for world peace and an end to suffering.

A popular fictional version of the tale is that Sadako folded 644 cranes before she died; her classmates then continued folding cranes in honor of their friend. This version of her story has been refuted by the Hiroshima Peace Museum[9] and her family.[10] She was buried with many cranes, folded both by Sadako herself and her classmates. While her effort could not extend her life, it moved her friends to make a statue of Sadako in the Hiroshima Peace Park. Every year 10,000,000 cranes are sent to Hiroshima and placed near the statue.[11] A group of one thousand paper cranes is called senbazuru in Japanese (千羽鶴).

The tale of Sadako has been dramatized in many books and movies. Sadako's older brother, Masahiro Sasaki co-wrote Sadako's complete story in English, as he remembers it, in hope of dispelling the many fictionalized versions of his sister's story.[12]

Notes and references

- Nick Robinson, The Origami Bible (2004), p. 10.

- Lang, Robert James. (1988). The Complete Book of Origami: Step-by Step Instructions in Over 1000 Diagrams/48 Original Models. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25837-8

- Hatori Koshiro. "History of Origami". K's Origami. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- Wang-Iverson, Patsy (2011). Origami 5: Fifth International Meeting of Origami Science, Mathematics, and Education. A K Peters/CRC Press. ISBN 9781568817149.

- Johannes de Sacro Bosco (1498). J. Petit (ed.). "Uberrimum Joannis de Sacro Bosco Sphaere mundi commentum Petri Ciruelli, insertis etiam questionibus Petri de Aliaco". G. Mercatoris (Parisiis).

- Donna Serena da Riva. "Paper Folding in 15th century Europe".

- Margalit Fox (2 April 2005). "Akira Yoshizawa, 94, Modern Origami Master". The New York Times.

- Gimenez, Luis Fernando. "Origami: el arte del papel plegado". Centro de historia de zaragoza, 2009

- http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/exhibit_e/exh0107_e/exh01071_e.html

- https://sadakosasaki.com

- http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/www/contents/1319176286322/index.html

- https://sadakosasaki.com

Further reading

- David Lister. "The Lister List". British Origami Society. – A collection of 115 essays by a historian of origami.

External links

- Okamura Masao. "The History of Origami in Japan". Origami Tanteidan.