Hermann von Schrötter

Anton Hermann Victor Thomas Schrötter, name sometimes referred to as Hermann Schrötter von Kristelli (5 August 1870 – 6 January 1928) was an Austrian physiologist and physician who was a native of Vienna. He was the son of laryngologist Leopold von Schrötter (1837–1908), and grandson to chemist Anton Schrötter von Kristelli (1802–1875).

He studied medicine and natural sciences at the Universities of Vienna and Strasbourg, earning his medical degree in 1894, and during the following year receiving his doctorate of philosophy. Afterwards he worked under Carl Gussenbauer (1842–1903) at the University Hospital in Vienna and was an assistant to his father at the clinic of internal medicine. In the mid-1890s with physiologist Nathan Zuntz (1847–1920) and others, he began investigations involving physiological effects on the body associated with air pressure and altitude change. In 1896 made the first in a series of several high-altitude balloon ascents.

In 1910 Schrötter accompanied scientists Nathan Zuntz, Arnold Durig (1872–1961) and Joseph Barcroft (1872–1947) on an expedition to Tenerife, where he conducted research involving respiration and oxygenation at higher elevations. During the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, he worked with the Red Cross in Montenegro, afterwards serving as a physician during World War I (including a stint as Sanitätschef in Jerusalem). After the war he was director of Malariaspitals in Wieselburg, and following his discharge from military service, he was in charge of the Alland Lungenheilanstalt (lung hospital founded by his father in 1898). In the 1920s he made balneological studies of the Dead Sea, and in 1925 was habilitated for internal medicine at the University of Vienna.

Schrötter was a pioneer of aviation and hyperbaric medicine, and made important contributions in the study of decompression sickness. In 1906, Schrötter suggested the use of oxygen with recompression, but concerns over oxygen toxicity kept the suggestion from becoming the standard practice that it is today.[1] He was interested in the physiological effects that divers experienced when ascending from ocean depths, as well as the effects that higher altitudes placed upon balloonists and mountain climbers.

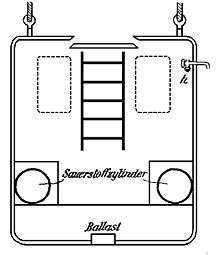

On 31 July 1901 meteorologists Arthur Berson (1859–1942) and Reinhard Süring (1866–1950) aboard the balloon Preussen, and equipped with portable compressed oxygen containers, were able to reach 10,800 meters above sea level. However, at 10,000 meters the two scientists succumbed to unconsciousness, and from this experiment Schrötter realized that even 100% oxygen would be an insufficient safeguard against hypoxia at very high altitudes. He recognized that special pressurized breathing equipment would be necessary to maintain sufficient blood oxygenation, and proposed using a pressurized sealed chamber for very high altitude balloon flights.[2]

Schrötter did extensive research involving pulmonary tuberculosis, and was a pioneer of bronchoscopy. In 1905 with Adolf Loewy (1862–1937), he was the first to use an endobronchial catheter as an instrument for airway separation in humans.

Selected written works

- Beobachtungen über physiologische Veränderungen der Stimme und des Gehörs bei Änderung des Luftdruckes (Observations on physiological changes in voice and hearing due to changes of air pressure), with Richard Heller and William Mager, (1897)

- Zur Kenntnis der Bergkrankheit (Knowledge of mountain sickness); (1899)

- Luftdruckerkrankungen. Mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der sogenannten Caissonkrankheit (Air pressure disorders. With particular reference to decompression illness), with Richard Heller and William Mager, (1900)

- Ueber eine seltene Ursache einseitiger Recurrenslähmung, zugleich ein Beitrag zur Symptomatologie und Diagnose des offenen Ductus Botalli (1901)

- Ergebnisse zweier Ballonfahrten zu physiologischen Zwecken (Results of two balloon experiments for physiological purposes) with Nathan Zuntz, (1902)

- Untersuchungen über Blutcirculation beim Menschen (Blood circulation studies on humans); with Adolf Loewy (1905)

- Klinik der Bronchoskopie (Hospital broncoscopy), (1906)

- Hygiene der Aeronautik und Aviatik (Hygiene of aeronautics and aviation); (1912)

- Vorträge über Tuberkulose für Ärzte (Lectures for physicians about tuberculosis), (1913)

- Skizzen eines Feldarztes aus Montenegro (Sketches of a field doctor at Montenegro), (1913)

- Das Tote Meer. Beitrag zur physikalischen Geographie und Balneologie mit Bemerkungen zur Flora der Ufergelände (The Dead Sea; Contribution to the physical geography and balneology with comments on the flora of the shore area), (1924)

- Über den Energieverbrauch bei musikalischer Betätigung (Excess energy consumption in musical activity), with Adolf Loewy (1926)

References

- Acott, C. (1999). "A brief history of diving and decompression illness". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- Aeronauts will use oxygen. New York Times, November 21, 1903

Bibliography

- Parts of this article are based on a translation of an equivalent article at the German Wikipedia, whose sources include: Schrötter, Hermann Anton @ NDB/ADB Deutsche Biographie and Hermann von Schrötter @ Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 1815–1950.

- Essay on Hypoxia