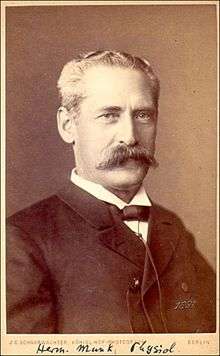

Hermann Munk

Hermann Munk (3 February 1839 – 1 October 1912) was a German physiologist. He was born at Posen, studied at Berlin and Göttingen, and in 1862 became docent in the former university. Seven years afterward he was promoted to assistant professor, and in 1876 to professor of physiology at the veterinary college at Berlin. Besides studies on the productive methods of threadworms, Munk wrote on the physiology of the nerves and especially on the brain.

Hermann Munk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | |

| Nationality | German |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Physiologist |

Visual cortex

Hermann Munk made important contributions to the field of psychology regarding the route from the eye to the brain through his meticulous research methods.[1] In 1878, he published findings from studies involving dogs and monkeys that led to the conclusion that vision was localized in the occipital cortical area. Amid scrutiny, he repeated his study and published similar findings in 1881. His focus was on dogs and he, unlike many others of his time, kept his subjects alive for an average of 5 years in order to study long-term effects.[2]

Throughout his research he discovered that cortical lesions in the visual areas lead to blindness. He called blindness experienced after the posterior portion of the occipital cortex was damaged Seelenblindheit, or psychic blindness. While suffering from psychic blindness, dogs were able to navigate effectively but showed no sign that they recognized what the objects in front of them were when they were only allowed to use sight. The dogs normally recovered from psychic blindness in 4 to 6 weeks and did appear to relearn faster than they first learned object meanings. The second type of blindness, Rindenblindheit, or cortical blindness, results from much larger lesions in the occipital cortex. Cortical blindness appears as a complete loss of vision and shows that vision involves areas surrounding the occipital cortex.[2]

Selected bibliography

- Untersuchungen über das Wesen der Nervenerregung (1868)

- Ueber die Funktionen der Grosshirnrinde (1881; second edition, 1890)

- Ueber die Ausdehnung der Sinnessphären in der Grosshirnrinde (1901–1902)

- Ueber die Functionen des Kleinhirns (1906–1908)

- Zur Anatomie und Physiologie der Sehsphäre der Grosshirnrinde (1910)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

References

- The Human Brain and Spinal Cord: A Historical Study Illustrated by Writings from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. By Edwin Clark and C.D. O’Malley copyright 1996 Norman Publishing

- Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations into Brain Function by Stanley Finger, Oxford University Press, 2001