Heriot Row

Heriot Row is a highly prestigious street in central Edinburgh, virtually unchanged since its original construction in 1802. From its inception to the present day in remained a top address in the city and has housed the rich and famous of the city's elite for 200 years

History

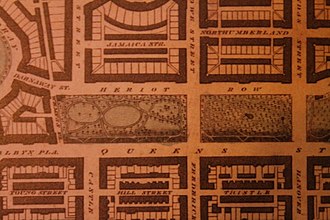

Following the success of Edinburgh's First New Town (from Princes Street to Queen Street) it was proposed to expand the concept northwards onto what was then fairly open land largely owned by the Heriot Trust. The scheme was designed by William Sibbald with the young Robert Reid working mainly on the proportions of the palace type frontages. The project was built by John Paton and David Lind. The two main sections were complete by 1808. The short western section (linking to Darnaway Street then the Moray Estate was slightly later and was executed in 1817 to the design of Thomas Bonnar being built by William & Wallace.[1]

The original concept was for two palace-fronted blocks: Dundas Street to Howe Street; and Howe Street to India Street. The short westmost section was originally planned as part of Darnaway Street and only after construction was it deemed part of Heriot Row.[2]

The original design concept was exceptionally modest: two storey and basement other than the end pavilions and central pavilions, which were set at three storey. Bonnar's west section was all three storeys. In 1864 David Bryce drew up a plan to add a third storey to all the western (central) section, but as this was in mixed ownership not all owners added this. The end result is an irretrievable ragged skyline to the west end of the central section (but the east end of the central section was successfully extended).[3]

The terraces run from Dundas Street to Gloucester Lane, the latter being off the New Town rectangular grid as it is a medieval lane linking Stockbridge to St Cuthbert's Church (which is also of medieval foundation). The lane marks a parish boundary.[4]

Queen Street Gardens

Queen Street Gardens is divided into three sections, two of which lie opposite Heriot Row (the eastern section is opposite Abercromby Place).[5]

John Ainslie's map of 1804 shows the gardens prior to their becoming a large common pleasure garden serving both Queen Street and Heriot Row properties (a function it still serves). The gardens were formalised as a single communal (but private) space by 1836.[6]

The east end of the garden opposite 1 Heriot Row was designed by the artist Andrew Wilson.[7]

The central section of garden contains a small pond with a central island. This gives credence to the story that it inspired Robert Louis Stevenson to write "Treasure Island" as his former house looks straight at the island.[8]

The small "Grecian temple" in the eastern garden seems to deceive most people and many bizarre stories exist explaining its "history". It has no history. It is disguising a gas governor and was erected in 1988 by British Gas. It is constructed of stone-coloured glass reinforced plastic.[9]

Heriot Row Residents

Were the blue plaque scheme carried out on Heriot Row it would look like an attack of the measles as almost every house merits two or three plaques. Instead there is a general agreement that plaques are not appropriate on this street. An explanatory panel at the end of the stret might prove both useful and more appropriate. The street numbers from east to west, starting at Dundas Street.

- 1 - Peter Spalding, philanthropist

- 2 - Major Cecil Cameron. spymaster

- 3 - James Ballantyne, Scott's publisher

- 4 - Rear Admiral William Duddingston

- 4 - Elizabeth Grant, diarist

- 4 - Christopher Johnston, Lord Sands, law lord

- 4 - (as an office) John Poulson

- 6 - Henry Mackenzie, author

- 6 - William Gloag, Lord Kincairney, law lord

- 7 - James Muirhead, scholar and book collector and his father Claud Muirhead printer

- 7 - William Smith Greenfield, anatomist

- 10 - Sir Byrom Bramwell, brain surgeon

- 10 - Lionel Daiches, lawyer

- 11 - Robert Hodshon Cay, advocate

- 12 - James Duncan, surgeon associated with chloroform

- 12 - James Gulliver, entrepreneur

- 13 - George Ballingall, surgeon

- 13 - Dr John Fraser, commissioner of lunacy

- 13 - John Phin, author

- 15 - Campbell Riddell colonial administrator of NSW

- 15 - Robert Munro, 1st Baron Alness MP

- 15 - James Frederick Ferrier, lawyer and poet

- 17 - Thomas Stevenson and his son Robert Louis Stevenson, author

- 17 - Patrick Balfour, Baron Kinross

- 21 - John Lessels, architect

- 26 - Thomas Clouston, physician

- 28 - Sir Andrew Douglas Maclagan, surgeon

- 29 - Sir William Newbigging, surgeon, and his son Patrick Newbigging

- 30 - James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon

- 31 - Jemima Blackburn, artist and author

- 31 - James Clerk Maxwell, scientist

- 31 - Alexander Ure politician and judge

- 31 - Alexander Asher, lawyer and politician

- 32 - Charles Shaw, Lord Kilbrandon, law lord

- 32 - George Deas, Lord Deas, law lord

- 32 - William Campbell Johnston, lawyer and cricketer

- 37 - Alexander Graham Munro, artist

- 38 - James Ormiston Affleck, surgeon

- 39 - Sir James Patten-McDougall

- 40 - Patrick Shaw, lawyer

- 41 - Finlay Dun, musician

- 46 - Sir Archibald Alison, 1st Baronet

- 47 - Sir William Dunbar, 7th Baronet

Non-Residential Functions

- 19 - Midlothian and Peebles Lunacy Board (early 20th century)

- 19 - Seaforth Highlanders Association

References

- The Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh by Gifford, McWilliam and Walker

- James Kay's plan of Edinburgh 1836

- The Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh by Gifford, McWilliam and Walker

- The Making of Classical Edinburgh, A J Youngson

- Edinburgh Street Atlas

- Joh Kay's map of Edinburgh 1836

- http://www.heriotrow.org/Andrew-Wilson/

- http://www.heriotrow.org/Robert-Louis-Stevenson/

- Edinburgh District Council planning records 1988