Herculine Barbin

Herculine Barbin (November 8, 1838 – February 1868)[1] was a French intersex person who was assigned female at birth and raised in a convent, but was later reclassified as male by a court of law, after an affair and physical examination. She is known for her memoir, Herculine Barbin, which was studied by Michel Foucault.

Early life

Most of what we know about Barbin comes from her later memoirs. Herculine Adélaïde Barbin was born in Saint-Jean-d'Angély in France in 1838. She was assigned as a girl and raised as such; her family named her Alexina. Her family was poor but she gained a charity scholarship to study in the school of an Ursuline convent.

According to her account, she was enamoured of an aristocratic female friend in school. She regarded herself as unattractive but sometimes slipped into her friend's room at night and was sometimes punished for it. Her studies were successful and in 1856, at 17, she was sent to Le Château to study to become a teacher. There, she fell in love with one of her teachers.

Puberty

Although Barbin was in puberty, she had not begun to menstruate and remained flat chested. The hairs on her cheeks and upper lip were noticeable.[2]

In 1857 Barbin received a position as an assistant teacher in a girls' school. She fell in love with another teacher, Sara, and demanded that only Sara should dress her. Sara's ministrations turned into caresses and they became lovers. Eventually, rumors about their affair began to circulate.

Barbin, although in poor health her whole life, began to suffer excruciating pains. When a doctor examined her, he was shocked and asked that she should be sent away from the school, but she stayed.

Eventually, the devoutly Catholic Barbin confessed to Jean-François-Anne Landriot, the Bishop of La Rochelle. He asked Barbin's permission to break the confessional silence in order to send for a doctor to examine her. When Dr. Chesnet did so in 1860, he discovered that although Barbin had a small vagina, she had a masculine body type, a very small penis, and testicles inside her body. In 20th-century medical terms, she had male pseudohermaphroditism.

Reassignment as male

A later legal decision declared officially that Barbin was male. She left her lover and her job, changed her name to Abel Barbin and was briefly mentioned in the press. She moved to Paris where she lived in poverty and wrote her memoirs, reputedly as a part of therapy. In the memoirs, Barbin would use female pronouns when writing about her life prior to sexual redesignation and male pronouns, including Alexina and Camille, following the declaration.[3] Nevertheless, Barbin clearly regarded herself as punished, and "disinherited", subject to a "ridiculous inquisition".

In his commentary to Barbin's memoirs, Michel Foucault presented Barbin as an example of the "happy limbo of a non-identity", but whose masculinity marked her from her contemporaries.[4] Morgan Holmes states that Barbin's own writings showed that she saw herself as an "exceptional female", but female nonetheless.[4]

Death

In February 1868, the concierge of Barbin's house in rue de l'École-de-Médecine found her dead in her home. She had died by suicide by inhaling gas from her coal gas stove. The memoirs were found beside her bed.

Memoirs publication

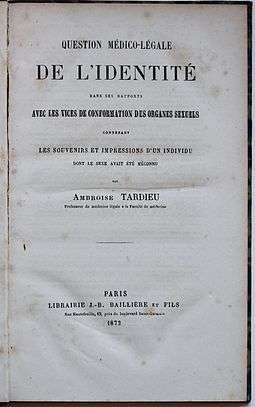

Dr. Regnier reported the death, recovered the memoirs and performed an autopsy. Later he gave the memoirs to Auguste Ambroise Tardieu, who published excerpts as "Histoire et souvenirs d'Alexina B." ("The Story and Memoirs of Alexina B.") in his book Question médico-légale de l'identité dans ses rapport avec les vices de conformation des organes sexuels, contenant les souvenirs et impressions d'un individu dont le sexe avait été méconnu ("Forensics of Identity Involving Deformities of the Sexual Organs, along with the Memoirs and Impressions of an Individual whose Sex was Misidentified") (Paris: J.-B. Ballière et Fils, 1872). The excerpts were translated into English in 1980.

Michel Foucault discovered the memoirs in the 1970s while conducting research at the French Department of Public Hygiene. He had the journals republished as Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite. In his edition, Foucault also included a set of medical reports, legal documents, and newspaper articles, as well as a short story adaptation by Oscar Panizza.

Modern commentaries and references

According to Morgan Holmes, the anthropologist Gilbert Herdt has identified Barbin as providing a crisis for "modern ideology" through an identification as neither male nor female,[5] but Barbin's own writings describe a self-identification as female, albeit an exceptional female.[4]

Barbin's memoirs inspired the French film The Mystery of Alexina. Jeffrey Eugenides in his book Middlesex treats concurrent themes, as does Virginia Woolf in her book, Orlando: A Biography. Judith Butler refers to Foucault's commentary on Barbin at various points in her 1990 Gender Trouble, including her chapter "Foucault, Herculine, and the Politics of Sexual Discontinuity."

Barbin appears as a character in the play A Mouthful of Birds by Caryl Churchill and David Lan. Barbin also appears as a character in the play Hidden: A Gender by Kate Bornstein. Herculine, a full-length play based on the memoirs of Barbin, is by Garrett Heater. Kira Obolensky also wrote a two-act stage adaptation entitled The Adventures of Herculina.

In 2014, a manuscript entitled Dear Herculine by Aaron Apps won the 2014 Sawtooth Poetry Prize from Ahsahta Press.[6]

Commemoration

The birthday of Herculine Barbin on 8 November is marked as Intersex Day of Remembrance.

See also

- Intersex in history

- Intersex rights in France

- Timeline of intersex history

References

- Foucault, Michel (2013-01-30). Herculine Barbin. ISBN 9780307833099.

- Foucault, Michel (1980). Herculine Barbin. Pantheon. ISBN 9780394738628.

- Foucault, Michel (1980). Herculine Barbin. Pantheon. ISBN 9780394738628. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Holmes, Morgan (July 2004). "Locating Third Sexes" (PDF). Transformations Journal. Regions of Sexuality (8). ISSN 1444-3775.

- Herdt, Gilbert (1994). Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History. New York: Zone.

- Apps, Aaron (2015). Intersex: A Memoir. Tarpaulin Sky Press. ISBN 978-1-939460-04-2.

Sources and further reading

- Barbin, Herculine (1980). Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite. introd. Michel Foucault, trans. Richard McDougall. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50821-4.

- Dreger, Alice Domurat (Spring 1995). "Doubtful Sex: The Fate of the Hermaphrodite in Victorian Medicine". Victorian Studies. 38 (3): 335–370. ISSN 0042-5222. PMID 11609024.

- Holmes, Morgan (July 2004). "Locating Third Sexes" (PDF). Transformations Journal. Regions of Sexuality (8). ISSN 1444-3775.

- Lafrance, Mélisse (2002). "Uncertain Erotic: A Foucauldian Reading of Herculine Barbin dite Alexina B". SITES: The Journal of Contemporary French Studies. 6 (1): 119–131. doi:10.1080/10260210290021815. ISSN 1026-0218.

- Leroi, Armand Marie (2003). Mutants: On Genetic Variety and the Human Body. New York: Viking. pp. 217–222. ISBN 978-0-670-03110-8.

- Tardieu, Ambroise (1872). Question médico-légale de l'identité dans ses rapport avec les vices de conformation des organes sexuels, contenant les souvenirs et impressions d'un individu dont le sexe avait été méconnu (in French). Paris: J.-B. Ballière et Fils. pp. 48–159.