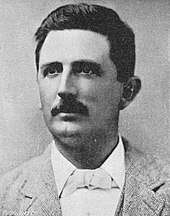

Henry Stirling Trigg

Henry Stirling Trigg (1860–4 November 1919), also known as Harry, was a prominent Western Australian architect. He was the grandson of Henry Trigg (Superintendent of Public Works in Western Australia from 1839 to 1851), and the first architect both born and trained in Western Australia.[1][2][3]

Life

Trigg's paternal grandfather, Henry Trigg, was the pioneer of the Congregational Church in Perth, and his maternal grandfather, Edmund Stirling, was influentially associated with the Inquirer, one of the first newspapers published in the colony. He was born in Perth in 1860, the son of Stephen Trigg. After leaving school, which he attended locally, Trigg entered the office of architect T. H. J. Brown, to whom he was articled. He gained a theoretical training at this office, and when his articles were completed he went to Sydney to practise for a couple of years. During his sojourn in the New South Wales capital he had the advantage of seeing some of the best architectural efforts in the Southern Hemisphere. Trigg returned to Perth in 1884.[3]

On 14 September 1881, Trigg married Miriam[1][2] Rogers, daughter of Ishmael Rogers of Perth.[4][5][6] Trigg designed a house for his family, known as "The Grange". It was built for a semi-tropical climate, with broad verandahs and high ceilings.[3]

In 1904, Trigg took his family on a tour of England, expecting to return in November. However, Trigg's youngest child was born there in late 1904, delaying their return until 1905. While away, Trigg left his brother Bayley in charge of his affairs in Australia. Bayley's financial mismanagement, or perhaps embezzlement, led to Trigg eventually facing bankruptcy court. Facing past creditors and the humiliation of insolvency, Trigg and his family left the state, eventually settling in Henley Beach, South Australia. Trigg died on 4 November 1919 following a horse and buggy accident in Springton, South Australia.[1][2][7]

Works

Trigg took a prominent part in building up the city of Perth, which upon his return in 1884 had few ornate buildings or large warehouses. One of the large buildings to be erected was the Daily News newspaper office, the plans of which Trigg prepared. At the time of its erection it was the only building of special architectural merit in the colony. With the advent of prosperity, people who were previously content with very modest edifices grew more particular, and demanded large houses and immense stores. There was a rush of orders for architects, and particularly for Trigg. In every part of the city are monuments of his work; one of his most notable works was the Congregational Church (modern-day Trinity Church) in St Georges Terrace. The façade is a vigorous treatment in American Romanesque, and shows the magnificent building off to advantage. The acoustic properties are excellent, and the whole edifice is equal to the best ecclesiastical buildings in Australia. Another structure designed by him is the office of the Commercial Union Insurance Company in St Georges Terrace, considered "the handsomest of its kind in the colony" in 1897 by historian Warren Bert Kimberly.[3]

Other buildings designed by Trigg include Sandover's, in the Italian style of architecture, the Royal Hotel in French Renaissance, and the Governor Broome Hotel in American Romanesque. Trigg's practice was not confined to Perth; he designed the Freemasons Hotel in Geraldton, one of the chief adornments of that port at the time.[3] Many of Trigg's works were designed in the American Romanesque style, including his own Trigg's Chambers at 39-41 Barrack Street, Perth, built 1896.[8]

Trigg designed churches in Leederville and Bunbury, church halls in Claremont and North Fremantle, the Subiaco Hotel, and various business premises, including on Geraldton's Marine Terrace for Edward Wittenoom. During the Western Australian gold rushes of the 1890s, Trigg made a multitude of Federation-era designs, such as the Rechabite Coffee Palace, the Goldfields Club Hotel, premises for Phineas Seeligson, and workshops for furniture dealer William Zimpel.[1]

References

Attribution

![]()

Sources

- Taylor, John J. "Harry Trigg" (PDF). Western Australian Architect Biographies. Australian Institute of Architects. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Taylor, John J (2009). Joseph John Talbot Hobbs (1864–1938) and his Australian-English Architecture (PDF) (PhD). University of Western Australia. pp. 47–50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Kimberly, W. B. (1897). "Henry Stirling Trigg, F.R.I.V.A". History of West Australia: A narrative of her past together with biographies of her leading men. F.W. Niven. pp. 110–111. Retrieved 21 January 2020 – via Wikisource.

- "Marriage". The West Australian. 19 September 1891. p. 4. Retrieved 26 January 2020 – via Trove.

- "Marriage". The Daily News. 18 September 1891. p. 2. Retrieved 26 January 2020 – via Trove.

- "General News". The Inquirer And Commercial News. Western Australia. 16 September 1891. p. 7. Retrieved 22 January 2020 – via Trove.

- "Tragedy at Springton". The Leader. South Australia. 7 November 1919. p. 3. Retrieved 22 January 2020 – via Trove.

- East, John W (1 January 2016). Australian Romanesque: A history of Romanesque-inspired architecture in Australia. The University of Queensland. pp. 37, 139–147. Retrieved 21 January 2020.