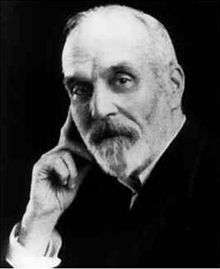

Henry Dudeney

Henry Ernest Dudeney (10 April 1857 – 23 April 1930) was an English author and mathematician who specialised in logic puzzles and mathematical games. He is known as one of the country's foremost creators of mathematical puzzles.[1]

Henry Dudeney | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Henry Ernest Dudeney 10 April 1857 Mayfield, East Sussex, England |

| Died | 24 April 1930 (aged 73) Lewes, Sussex, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | Puzzles, mathematical games |

Early life

Dudeney was born in the village of Mayfield, East Sussex, England, one of six children of Gilbert and Lucy Dudeney. His grandfather, John Dudeney, was well known as a self-taught mathematician and shepherd; his initiative was much admired by his grandson. Dudeney learned to play chess at an early age, and continued to play frequently throughout his life. This led to a marked interest in mathematics and the composition of puzzles. Chess problems in particular fascinated him during his early years.

Career

Although Dudeney spent his career in the Civil Service, he continued to devise various problems and puzzles. Dudeney's first puzzle contributions were submissions to newspapers and magazines, often under the pseudonym of "Sphinx." Much of this earlier work was a collaboration with American puzzlist Sam Loyd; in 1890, they published a series of articles in the English penny weekly Tit-Bits.

Dudeney later contributed puzzles under his real name to publications such as The Weekly Dispatch, The Queen, Blighty, and Cassell's Magazine. For twenty years, he had a successful column, "Perplexities", in The Strand Magazine, edited by the former editor of Tit-Bits, George Newnes. Dudeney continued to exchange puzzles with fellow recreational mathematician Sam Loyd for a while, but broke off the correspondence and accused Loyd of stealing his puzzles and publishing them under his own name.

Some of Dudeney's most famous innovations were his 1903 success at solving the Haberdasher's Puzzle (Cut an equilateral triangle into four pieces that can be rearranged to make a square) and publishing the first known crossnumber puzzle, in 1926. He has also been credited with discovering new applications of digital roots. Dudeney was a leading exponent of verbal arithmetic puzzles; his were always alphametic, where the letters constitute meaningful phrases or associated words.

Previously, it had been claimed (though not by Dudeney himself) that he was the inventor of verbal arithmetic. This was later refuted by the counter example of a verbal arithmetic puzzle published in the US in 1864.[2]

Omission of detailed puzzle rules in the cited farm journal suggests they were already popular in America by 1864, when Dudeney was 7 years old. The popularity of these puzzles guarantees they'd be well known by then to Sam Loyd, an American puzzler and early Dudeney puzzle collaborator. Loyd has gained notoriety (at the expense of credibility) for his own claims of invention now exposed as false. He claimed to have invented the verbal arithmetic puzzle. For another example of Loyd's pervasive deceit, see 15 puzzle. Dudeney experienced Loyd's duplicity and intellectual theft first hand, eventually publicly equating Loyd with the Devil.

Both Dudeney and Loyd were featured by Martin Gardner in his Mathematical Games column in Scientific American—Loyd in August 1957 and Dudeney in June 1958.[3]

Personal life

In 1884 Dudeney married Alice Whiffin (1864–1945). She later became a very well known writer who published many novels as well as a number of short stories in Harper's Magazine under the name "Mrs. Henry Dudeney". In her day, she was compared to Thomas Hardy for her portrayals of regional life. The income generated by her books was important to the Dudeney household, and her fame gained them entry to both literary and court circles.

After losing their first child at the age of four months in 1887, the Dudeneys had one daughter, Margery Janet (1890–1977). She married (John) Christopher Fulleylove, son of John Fulleylove and one of an esteemed family of English artists. The Fulleyloves emigrated to North America, first living in Canada and eventually settling first in Oakland, Michigan, and later New York. They had three sons: John Gabriel (died in infancy), James Shirley, and Julian John ("Barney"); and two daughters: Catherine and Elizabeth Ann ("Nancy").

Alice's personal diaries were edited by Diana Crook and published in 1998 under the title A Lewes Diary: 1916–1944. They give a lively picture of her attempts to balance her literary career with her marriage to her brilliant but volatile husband.

Death

In April 1930, Dudeney died of throat cancer in Lewes, where he and his wife had moved in 1914 after a period of separation to rekindle their marriage. Alice Dudeney survived him by fourteen years and died on 21 November 1945, after a stroke.

Both are buried in the Lewes town cemetery. Their grave is marked by a copy of an 18th-century Sussex sandstone obelisk, which Alice had copied after Ernest's death to serve as their mutual tombstone.

Publications

- The Canterbury Puzzles (1907)

- Amusements in Mathematics (1917)

- The World's Best Word Puzzles (1925)

- Modern Puzzles (1926)

- Puzzles and Curious Problems (1931, posthumous)

- A Puzzle-Mine (undated, posthumous)

See also

References

- Newing, Angela (1994), "Henry Ernest Dudeney: Britain's Greatest Puzzlist", in Guy, Richard K.; Woodrow, Robert E. (eds.), The Lighter Side of Mathematics: Proceedings of the Eugène Strens Memorial Conference on Recreational Mathematics and Its History, Cambridge University Press, pp. 294–301, ISBN 9780883855164.

- "Puzzle No. 109". American Agriculturist. 23 (12): 349. December 1864.

- Gardner, Martin (1995), 536 Curious Problems & Puzzles: Introduction, Barnes & Noble Books, ISBN 1-56619-896-8

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henry Dudeney |