Henry Cotton (judge)

Sir Henry Cotton (20 May 1821 – 22 February 1892) was a British judge. He was a Lord Justice of Appeal from 1877, when he was made a Privy Counsellor, until his retirement in 1890.

Early life

He was born in Leytonstone. His father William Cotton later became Governor of the Bank of England. His brother William Charles Cotton was a clergyman and beekeeper. His sister Sarah married Sir Henry Acland, who founded Acland Hospital in her memory.[1]

He attended Eton College, and later Christ Church, Oxford, where he was a student until 1852. He graduated B.A. in 1843.[2]

Career

He entered Lincoln's Inn in 1843 and was called to the bar in 1846. He quickly acquired a large practice in the equity courts, and through the influence of his father was appointed standing counsel to the Bank of England. In 1866, he took silk and attached himself to the court of Vice-chancellor (Sir) Richard Malins, where he shared the leadership with Mr. W. B. Glasse.

Among the important cases in which he was engaged were the liquidation of Overend, Gurney, & Co.; the King of Hanover v. the Bank of England; Rubery v. Grant; Dr.Hayman v. the Governors of Rugby School; and the Republic of Costa Rica v. Erlanger. In 1872 he was appointed standing counsel to the university of Oxford, and shortly afterwards only went into court on a special retainer.[2]

He became Lord Justice of Appeal in 1877 upon the death of Sir George Mellish. He became a member of the privy council, and was knighted.[2]

Judgments

Judgments of Cotton include:

- Tamplin v James (1880) 15 Ch D 215 (CA) – English contract law case concerning the availability of specific performance for a breach of contract induced by mistake.[3]

- Imperial Hydropathic Hotel Co v Hampson (1883) LR 23 Ch D 1 – UK company law concerning the interpretation of a company's articles of association in the matter of a removal of a company director.

- Hutton v West Cork Rly Co (1883) 23 Ch D 654 – company law case concerning the limits of a director's discretion to spend company funds for the benefit of non-shareholders.

- Isle of Wight Rly Co v Tahourdin (1884) LR 25 Ch D 320 – a UK company law case on removing directors under the Companies Clauses Act 1845.

- Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459 – contract law case, concerning misrepresentation

- Allcard v Skinner (1887) 36 Ch D 145 – contract law case dealing with undue influence and English unjust enrichment law.

- Learoyd v Whiteley [1887] UKHL 1, (1887) 12 AC 727 – English trusts law case, concerning the duty of care owed by a trustee when exercising the power of investment.

Family life

He was an avid sportsman, having been an oarsman at Eton, and in later life a skater.

On 16 August 1853 he married Clemence Elizabeth, daughter of Thomas Streatfeild.

His father's Wallwood estate was sold off posthumously in 1874, but Henry Cotton set aside and donated a plot of land upon which St. Andrew's Church in Leytonstone was built.[4][5]

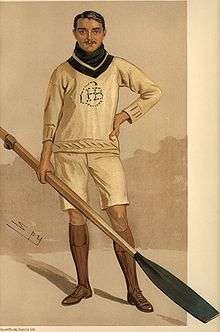

His youngest son Hugh Benjamin Cotton (1871–1895) was featured in a Vanity Fair caricature on 15 March 1894 as president of the Oxford University Boat Club, but died of lung illness the following year in Davos Platz, Switzerland.[6][7]

Through his grandfather Joseph Cotton (1746–1825), Henry Cotton was a cousin of the African explorer William Cotton Oswell and a first cousin once removed of Henry John Stedman Cotton.[8][9]

Notes

- "Acland, Henry Wentworth, 1815-1900", Dictionary of National Biography

- Cotton 1901.

- "Contract – General Principles – Remedies – Specific Performance and Injunctions – Specific Performance". The Laws of Australia. Thomson Reuters. 31 August 2006. pp. [7.9.1450].

- "Brief History". St. Andrew's Church website. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Conservation area appraisal: Leytonstone Conservation Area" (PDF). Waltham Forest Council website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Hugh Benjamin Cotton 1871 – 1895". Halhed genealogy & family trees. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Boat Race 1890–1899". Thames.me.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- "Relationship Calculator: Henry Cotton relationship to William Cotton Oswell". Halhed genealogy & family trees. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Relationship Calculator: Henry Cotton relationship to Henry John Stedman Cotton". Halhed genealogy & family trees. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Attribution

![]()

Sources

- Cotton, J. S.; (rev.) Mark Curthoys (2004). "Cotton, Sir Henry (1821–1892)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

External links

- "Henry Cotton 1821 – 1892". Halhed genealogy & family trees. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Foster, Joseph. Alumni Oxoniensis (1715–1886). I. Oxford: Parker & Co. p. 302. Retrieved 19 February 2011.