Henry Burton (theologian)

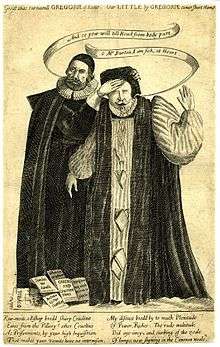

Henry Burton (Yorkshire, 1578–1648), was an English puritan. Along with John Bastwick and William Prynne, Burton's ears were cut off in 1637 for writing pamphlets attacking the views of Archbishop Laud.

Early life

He was born at Birstall, West Yorkshire, a small parish in the West Riding of Yorkshire, in the latter part of 1578 as may be inferred from his writings. His father, William Burton, was married to Maryanne Homle [Humble] on 24 June 1577. He was educated at St. John's College, Cambridge, where he graduated M.A. in 1602.[1] His favourite preachers were Laurence Chaderton and William Perkins. On leaving the university he became tutor to two sons of Sir Robert Carey.

Under James I

Through the Carey interest, Burton obtained the post of clerk of the closet to Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales; while acting in this capacity he composed a treatise on Antichrist, the manuscript of which was placed by the prince in his library at St. James's. He complains that Richard Neile, who was clerk of the closet to King James, opposed his advancement; however, on Prince Henry's death (6 November 1612) Burton was appointed clerk of the closet to Prince Charles. On 14 July 1612 he had been incorporated M.A. at Oxford, and was again incorporated on 15 July 1617. He tells us that at the age of thirty he resolved to enter the ministry. Thomas Fuller says that he was to have attended Prince Charles to Spain (17 February 1623) for the Spanish Match, and that for some unknown reason the appointment was countermanded. Burton does not mention this, but says that he could not get a license for a book which he wrote in 1623 against the Converted Jew by John Percy alias Fisher the Jesuit, to refute Arminianism and prove the Pope to be Antichrist. He had, in fact, thrust himself into a discussion then going on between Fisher and George Walker, minister of St. John's, Watling Street.

Under Charles I

On the accession of Charles, Burton took it as a matter of course that he would become clerk of the royal closet, but Neile was continued in that office. Burton lost the appointment through an indiscretion. On 23 April 1625, before James had been dead a month, Burton presented a letter to Charles, inveighing against the popish tendencies of Neile and William Laud (who in Neile's illness was acting as clerk of the closet). Charles read the letter partly through, and told Burton 'not to attend more in his office till he should send for him.' He was not sent for, and did not reappear at court. He deplored the death of James, for the influence he saw the late king had had in regarding the nascent high-church movement.

He was almost immediately presented to the rectory of St. Matthew's, Friday Street, and used his city pulpit to campaign aggressively against episcopal practices. He began to deviate from the set ceremonies, and was cited before the Court of high commission in 1626, but the proceedings were stopped. Bishop after bishop became the subject of his attack. For a publication[2] which bore a frontispiece representing Charles in the act of assailing the pope's triple crown, he was summoned, in 1627, before the privy council, but again got off, in spite of Laud. His Babel no Bethel (1629) in reply to the Maschil of Robert Butterfield, earned him a temporary suspension from his benefice, and a spell in the Fleet Prison. More serious troubles were to come. On 5 November 1636 he preached two sermons in his own church on Proverbs xxiv. 21, 22, in which he charged the bishops with innovations amounting to a popish plot. His pulpit style was perhaps effective, but certainly not refined; he calls the bishops caterpillars instead of pillars, and 'antichristian mushrumps.' Next month he was summoned before Arthur Duck, a commissioner for causes ecclesiastical, to answer on oath to articles charging him with sedition. He refused the oath, and appealed to the king. Fifteen days afterwards he was cited before a special high commission at Doctors' Commons, did not appear, and was in his absence suspended and ordered to be apprehended.

He shut himself up in his house, and published his sermons, with the title, For God and the King (1636). On 1 February 1637 his doors were forced, his study ransacked, and he was taken into custody and sent next day to the Fleet. Peter Heylyn wrote a Briefe Answer to Burton's sermons.

Star Chamber conviction

In prison Burton was soon joined by William Prynne and John Bastwick, a parishioner who had also written books against the Church hierarchy, and the three were proceeded against in the Star-chamber (11 March) and included in a common indictment. An attempt was made on 6 June to get the judges to treat the publications of Bastwick and Burton (who had added to his offence by publishing, from his prison, An Apology for an Appeale, 1636 consisting of epistles to the king, the judges, and the nobility) as presenting a primâ facie case of treason, but this fell through. The defendants prepared answers to the indictment, but it was necessary that these should be signed by two counsel. Burton was the only one who got at length the signature of a counsel, one Holt, an aged bencher of Gray's Inn, and Holt drew back, until the court agreed to accept his single signature.

Burton's answer lay in court about three weeks, when on 19 May the attorney-general, Sir John Bankes, denouncing it as scandalous, referred it to the chief justices, Sir John Bramston and Sir John Finch. They made short work of it, striking out sixty-four sheets, and leaving no more than six lines at the beginning and twenty-four at the end. Thus mutilated, Burton would not own it; he was not allowed to frame a new answer, and on 2 June it was ordered that he, like the rest, should be proceeded against pro confesso. Sentence was passed on 14 June, the defendants crying out for justice, and demanding that they should not be condemned without examination of their answers. Burton, when interrogated as to his plea by the lord keeper Thomas Coventry, 1st Baron Coventry, maintained that 'a minister hath a larger liberty than always to go in a mild strain'. His defence was stopped. He was condemned to be deprived of his benefice, to be degraded from the ministry and from his academical degrees, to be fined £5,000, to be set in the pillory at Westminster and his ears to be cut off, and to be perpetually imprisoned in Lancaster Castle, without access of his wife or any friends, or use of pen, ink, and paper. For this sentence Laud thanked the court.

Burton's parishioners signed a petition to the king for his pardon; the two who presented it committed to prison. His ears were cropped so close, according to Thomas Fuller, that the temporal artery was cut. When his wounds were healed, and he was conveyed northward on 28 July, people lined the road at Highgate to take leave of him. His wife followed in a coach, and 500 on horseback accompanied him as far as St. Albans. At Lancaster, Burton was confined in a large smoky room without furniture; the gaps between the planks of the floor made it dangerous to walk, and underneath was a dark room in which were kept five witches. The allowance for diet was not paid. Dr. Augustine Wildbore, vicar of Lancaster, kept a watchful eye over Burton's reading; Lord Clarendon says that despite precautions, papers from Burton were circulated in London.

A pamphlet giving an account of his censure in the Star-chamber was published in 1637. On 1 November he was sent to Guernsey, where he arrived on 15 December and was shut up in a cell at Castle Cornet. Here he had no books except his bibles in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and French, and an ecclesiastical history in Greek, but he managed to get pen, ink, and paper, and wrote two books, which were not printed. His wife was not allowed to see him, though his only daughter died during his imprisonment.

Release and later life

On 7 November 1640 his wife presented a petition to the House of Commons for his release, and on 10 November the house ordered him to be sent to London. The order arrived at Guernsey on Sunday, 15 November and Burton embarked on the 21st. At Dartmouth, on the 22nd, he met Prynne, and their journey to London was again a triumphal progress. They were escorted from Charing Cross to the City of London. On 30 November Burton appeared before the House, and on 5 December presented a petition; the House on 12 March 1641 declared the proceedings against him illegal, and cast Laud and others in damages. On 24 March his sentence was reversed, and his benefice ordered to be restored; on 20 April a sum of £6,000 was voted to him; on 8 June a further order for his restoration to his benefice was made out. He recovered his degrees, and received that of B.D. in addition. The money was not paid, nor did he get his benefice, to which Robert Chestlin had been regularly presented.

On 5 October 1642 his old parishioners petitioned the House that he might be appointed Sunday afternoon lecturer, and this was done. Chestlin, who resisted the appointment, was imprisoned at Colchester for a seditious sermon; he escaped to the king at Oxford. Left thus in possession at St. Matthew's, Friday Street, Burton organised a church on the independent model. He preached before parliament, but did not approve the course which events subsequently took. He was for some time allowed to hold a catechetical lecture every Tuesday fortnight at St. Mary's, Aldermanbury, but on his introducing his independent views the churchwardens locked him out in September 1645. This led to an angry pamphlet war with Edmund Calamy, rector of the parish. During his imprisonment he suffered from kidney disease, which was probably the cause of his death. He was buried on 7 January 1648.

Works

S. R. Gardiner says of Burton's Protestation Protested, published in July 1641, that it 'sketched out that plan of a national church, surrounded by voluntary churches, which was accepted at the revolution of 1688.' He published a Vindication of Churches commonly called Independent, 1644 (in answer to Prynne), and exercised a strict ecclesiastical discipline within his congregation.

Burton's other main publications were:

- A Censvre of Simonie, 1624.

- A Plea to an Appeale, 1626.

- The Seven Vials; or a briefe Exposition upon the 15 and 16 chapters of the Revelation, 1628.

- A Tryall of Private Devotion, 1628.

- England's Bondage and Hope of Deliverance, 1641, sermon from Psalm liii 7, 8, before the parliament on 20 June).

- Truth still Truth, though shut out of doors, 1645, (distinct from Truth shut out of doores, a previous pamphlet of the same year).

- The Grand Impostor Unmasked, or a detection of the notorious hypocrisie and desperate impiety of the late Archbishop (so styled) of Canterbury, cunningly couched in that written copy which he read on the scaffold, &c. 4to, n.d.

- Conformities Deformity, 1646.

Family

He and his first wife, Anne, he had two children: Anne, baptised 21 September 1621, and Henry, baptised 13 May 1624, who married Ursula Maisters on 30 November 1647, and is described as a merchant. His second wife, Sarah, and son, Henry, survived him, and on 17 February 1652 petitioned the house for maintenance; the son received lands of £200 yearly value from the estates of certain delinquents, out of which his widow was to have £100 a year for life.

See also

Notes

- "Burton, Henry (BRTN595H)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- The Baiting of the Popes Bvll, &c., 1627,

References

- Henry Burton at Spartacus Educational

- Attribution