Henrieta Delavrancea

Henrieta Delavrancea (1897–1987) was a Romanian architect and one of the first female architects admitted to the Superior School of Architecture in Bucharest, but because of the suspension of her classes during World War I, she was not the first female to graduate. She was one of the most known women architects in Romania and a significant contributor to the modernist school of Romanian architecture, until state-controlled design in the communist era curtailed individuality.

Henrieta Delavrancea | |

|---|---|

| Born | 19 October 1897 |

| Died | 26 March 1987 (aged 89) Bucharest, Romania |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Other names | Henrieta Delavrancea-Gibory |

| Occupation | architect |

| Known for | First female admitted to the Superior School of Architecture in Bucharest |

| Spouse(s) | Emile Gibory (married in 1918) |

Biography

Henrieta Delavrancea was born on 19 October 1897 in Bucharest, Romania[1] to Maria Lupaşcu and Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea[2] Because her family was from the upper levels of society and her father was both a politician and a literary figure, Delavrancea grew up surrounded by noted members of Romanian society. One of those early mentors was Ion Mincu,[3][4] one of the most known Romanian architects and proponents of preservation of the nationalist identity for architecture.[5] In 1913, she enrolled in the Superior School of Architecture, in a class of twenty, with only one other woman, Marioara Ioanovici.[2] Though she was one of the first women admitted, she suspended her studies in 1916 because of the war.[6]

During World War I, she served as a nurse[6] and married Emile Gibory in 1918. They lived briefly in Paris and then moved to the mountains, living in Nehoiu. After two years, they moved to the area of Penteleu, Romania, but in 1924, Delavrancea decided to return to her studies.[2] In the 1926[6]-1927 term, she graduated with her diploma and claimed afterward to be the fourth female architect of the country after “Ada Zăgănescu, Virginia Andreescu and Mimi Friedman”. This may or may not be accurate as the Romanian Architects Society, showed six female registrants in 1924: Maria Cotescu, Irineu Maria Friedman, Virginia Andreescu Haret, Maria Hogas, Antonetta Ioanovici and Ada Zăgănescu.[7] On the other hand, Delavrancea designed her first home, called the "German House" in 1921 before she finished school while living in Nehoiu.[6] She also might have confused the names, as Zăgănescu studied privately with Ion Mincu and is acknowledged as the first practicing female architect,[2][8] Andreescu-Haret is recognized as the first graduate of the Superior school in 1919 and the first registered female architect,[6] and Cotescu graduated from the High School of Architecture in Bucharest in 1922.[9]

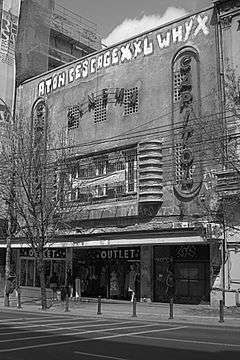

Her next project was her own home on Mihai Eminescu Street, which she designed in 1925.[1] Delavrancea designed many private and public buildings, among them 22 seaside houses in Balcic[7] including homes for General Gheorghe Rasoviceanu where Gheorghe Petrașcu painted between 1934 and 1935, Mircea Cancicov, Ion Pillat and Eliza Brătianu. She also designed a renovation to the City Hall, the Pavilion of the Border Guards, and the Tea Pavilion at the Balchik Palace, designed for Queen Marie of Romania.[10] She built 28 Villas throughout the country; 5 churches, including the renovation of the New St. George Church in Bucharest; the Snagov Palace for Prince Nicholas; worked on at least three health facilities—the Institutul Clinic Fundeni on the outskirts of Bucharest, the Filantropia Hospital[7] and the Headquarters of the Hygiene and Public Health Institute;[6] the Capitol Cinema in Bucharest; the French Consulate in Bucharest; the Prefecture Office in Oraviţa and many others.[7]

Delavrancea was one of the best known women architects in Romania and a significant contributor to the modernist movement.[3] Her many villas in the seaside town of Balcic (now Balchik, Bulgaria) built between 1934-38 are especially notable, taking traditional forms and local motifs and reinterpreting them in functional, modern design. Here she used rubble stone retaining walls and bases, low pitched tiled roof with wide projecting cornices, combined with plain white rectangular walls. Because of the unique foundation requirements of building on the coast, she employed corbelling and consoling techniques for support.[2] The Constantiniu House, built in 1935, is the most dramatically site and well known.[11]

In Bucharest one of her notable designs was a new modernist facade to the Capitol Theatre on Boulevardul Regina Elisabeta, built in 1938.[12] The design originally included a striking off-centre vertical fin, highlighted by neon. Her villa for Professor Victor Vâlcovici, at Strada Londra 44, built in 1937-38, with its clean lines and promenet curved corner window, is one of the most often reproduced images of modernist houses in Bucharest.[13]

After World War II, she worked on rehabilitation and preservation projects.[14] During the communist era, she worked for 19 years on the design team of the Ministry of Health,[1] as private practice was banned and design was controlled by the state until 1989.[14]

Delavrancea-Gibory, died on 26 March 1987 in Bucharest.[1] Several exhibitions featuring her work have been held since her death.[15][16] In 2011, a book entitled Henrieta Delavrancea Gibory arhitectură 1930-1940 edited by Militza Sion featured drawings and buildings by Delavrancea-Gibory.

Gallery

Capitol Cinema, Bucharest

Capitol Cinema, Bucharest

indra diaconu

Eliza Toia

Further reading

- Sion, Militza (2011). Henrieta Delavrancea Gibory: arhitectură 1930 - 1940 (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Simetria. ISBN 978-973-1872-10-0.*

References

- Marcu, George (2012). "Henrieta Delavrancea-Gibory". Bucurest, Romania: Enciclopedia României. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Stan, Simina (15 August 2009). "Henrieta Delavrancea Gibory" (in Romanian). Bucharest, Romania: Jurnalul. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Petrescu 2012, p. 7.

- "Să ne cinstim românii – episodul 29: Familia Delavrancea" (in Romanian). Bucharest, Romania: Scrie Liber. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Machedon & Scoffham 1999, p. 2.

- Niculae, Raluca Livia (2012). "Architecture, a career option for women? Romania case" (PDF). Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research. Pro Global Science Association. 4 (2): 8. ISSN 2247-6172. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Niculae, Raluca (2012). "Gender issues in architectural education: feminine paradigm" (PDF). Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research. Pro Global Science Association. 3 (1): 144–152. ISSN 2247-6172. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Petrescu 2012, p. 6.

- Machedon & Scoffham 1999, p. 286.

- Petrescu 2012, p. 63.

- "Henrieta Delavrancea - Constantiniu House, Balchik, 1935 (in Romanian)". ARCHITECTURE WORKSHOP LILIANA CHIABURU. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- "Henriette Gibory Delavrancea, among the first female architects in Romania (in Romanian)". FEEDER.ro. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- "Henrietta Delavrancea Gibory - Str. Londra nr. 44 - 1933". Flickr. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Feuerstein, Marcia; Bliznakov, Milka (2000). "New Acquisitions: Women Architects in Romania" (PDF). IAWA Newsletter. Blacksburg, Virginia: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 12: 1–4. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "Henrieta Delavrancea-Gibory" (in Romanian). Bucharest, Romania: Muzeul Naţional de Artă al României. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "Henrieta Delavrancea-Gibory, arhitectură 1930-1940" (in Romanian). Bucharest, Romania: Arhi Forum. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

Sources

- Machedon, Luminita; Scoffham, Ernie (1999). Romanian Modernism: The Architecture of Bucharest 1920-1940. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13348-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petrescu, Ioana-Maria (2012). "Pioneering Women Architects". In Teodorescu, Nicoleta Doina (ed.). Architecture Series, Vol II (PDF). 4. Bucharest, Romania: România de Mâine Foundation Publishing House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)