Henri Evrard, marquis de Dreux-Brézé

Henri Evrard, marquis de Dreux-Brézé (1762–1829) was a member of the French nobility who at the age of twenty-seven played a role in the meeting of the states-general in 1789. Brézé had succeeded his father Thomas as court master of the ceremonies to Louis XVI in 1781.[1]

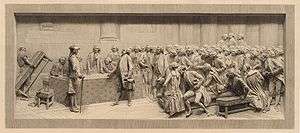

During the opening stages of the Estates-General of 1789 it fell to Brézé to regulate the questions of etiquette and precedence between the three estates. That as the immediate representative of the crown he would offend the susceptibilities of the deputies of the Third Estate was perhaps inevitable, but little attempt was made to adapt archaic etiquette to changed circumstances. Brézé did not formally intimate to President Bailly the proclamation of the royal séance until the 20th of June, when the carpenters were about to enter the hall to prepare for the event, thus provoking the session in the tennis court. After the royal séance Brézé was sent to reiterate Louis's orders that the estates should meet separately, when Mirabeau replied that the hall could not be cleared "except at the point of bayonets".[1] Brézé withdrew in the face of Mirabeau's aggressive stance but followed traditional protocol by walking slowly backwards with his embroidered tricorn on his head.

Brézé reported the defiance of the Third Estate back to the king, who was awaiting developments in the nearby royal apartments. Louis reportedly responded "Damn! Oh well let them stay".

After the fall of the Tuileries in 1792 Brézé emigrated for a short time, but though he returned to France he was spared during the Terror. At the Restoration he was made a peer of France, and resumed his functions as guardian of an antiquated ceremonial. He died on the 27th of January 1829, when he was succeeded in the peerage and at court by his son Scipion (1793–1845).[1]

References

-