Hemyock Castle

Hemyock Castle is a ruined 14th-century castle in the village of Hemyock, Devon, England. It was built by Sir William Asthorpe after 1380 to a quadrangular design. It would have been visually impressive, but not particularly functional, with various intrinsic flaws. By the 16th century it had fallen into ruin and, following its use during the English Civil War in the mid-17th century, it was pulled down. In the 21st century the site is occupied by the fragments of the original castle; and Castle House, an 18th-century house built within the site, and restored as private home at the end of the 20th century.

| Hemyock Castle | |

|---|---|

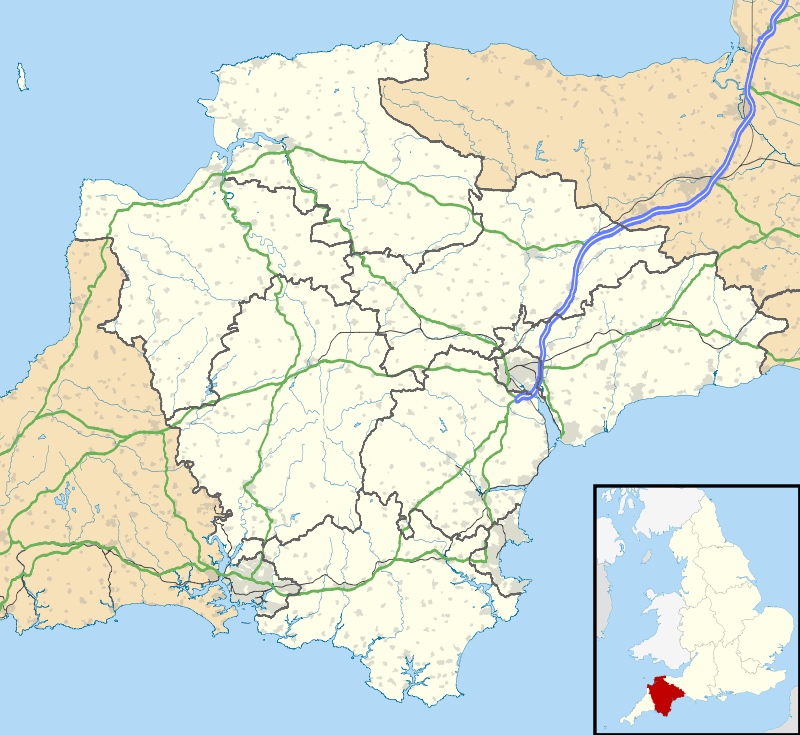

| Hemyock, Devon, England | |

Ruins of Hemyock Castle | |

Hemyock Castle | |

| Coordinates | 50°54′45″N 3°13′53″W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Chert stone rubble |

| Events | English Civil War |

History

11th-15th centuries

The castle is located in the Culm valley in the Blackdown Hills, on the west side of the village of Hemyock.[1] The site belonged to the Hidon family in the 11th and 12th centuries, passing by marriage into the Dynham family in the 13th.[2] In the 13th century a building was constructed on the current site, protected by a spring-fed moat.[3]

Sir William Asthorpe married Margaret Dynham in 1362.[3] This advantageous marriage made him a rich man and a member of the local elite, but he was an outsider in Devon society and his position was insecure.[3] In November 1380, Sir William Asthorpe acquired royal permission to build a new castle on the site.[3] The castle provided a degree of protection for Asthorpe, but it was also intended for show, to impress others with his status and authority.[4]

The castle was a built in the quadrangular design fashionable at the time, to a roughly square shape with circular towers linked by stone walls.[3] The full layout of the castle is uncertain, but a gatehouse, with twin towers and a portcullis, was positioned on the east side, and at least five other towers were positioned around the walls. The walls and towers were 4.5 feet (1.4 m) thick and built from chert stone rubble with occasional pieces of iron slag left over from the medieval metalworking around the village; they would originally have been whitewashed with lime.[5]

From the line of the walls, there may have been another entrance on the west side, but this is uncertain.[3] A bank of earth appears to have been erected to the north of the castle, either as a form of defence, or to obscure the castle from a road that ran past it from that direction.[6] Despite being visually impressive, the castle was not particularly functional, as the gatehouse was poorly designed and the towers had no usable rooms on the upper stories.[3]

16th-21st centuries

By the time that the antiquarian John Leland visited the castle in the early 16th century, it had fallen into ruin, and only a few towers remained intact.[3] By 1566, the centre of the castle was being used for growing apples.[6] In 1642, civil war broke out in England between the Royalist supporters of Charles I and the supporters of Parliament. Lord Poulett, a Royalist, seized the castle shortly after the outbreak of fighting.[7] During the war the castle was taken by Parliament and used as a prison.[7] In 1660, Charles II was restored to the throne and the castle was torn down.[7]

Between the 18th and 19th centuries, a building called Castle House was built inside the castle walls, using some parts of a former 15th-century building and reusing material from the castle walls and towers.[8] Towards the end of the 18th century, the upper parts of the towers were destroyed by the tenant of the estate.[7] At the end of the 18th century, the castle was bought by the British military officer, General John Simcoe; he remodelled Castle House, probably around 1800, in a Gothic style.[9]

The castle was restored from 1983 onwards, including various modern alterations to the Castle House.[10] In the 21st century the castle is protected under UK law as a II* listed building and a scheduled monument.[11]

References

- Mackenzie 1896, p. 32; Emery 2006, p. 577

- Mackenzie 1896, pp. 32–33

- Emery 2006, p. 577

- Emery 2006, p. 577; Davis, Philip, "Hemyock Castle", Gatehouse Gazette, retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Emery 2006, p. 577; Context One Archaeological Services (2009), "Land to the East of 'Castle Dene', Culmstock Road, Hemyock, Devon: an Archaeological Excavation and Watching Brief Assessment Report" (PDF), Context One Archaeological Services, pp. 5–6, retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Context One Archaeological Services (2009), "Land to the East of 'Castle Dene', Culmstock Road, Hemyock, Devon: an Archaeological Excavation and Watching Brief Assessment Report" (PDF), Context One Archaeological Services, p. ii, retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Mackenzie 1896, p. 33

- Context One Archaeological Services (2009), "Land to the East of 'Castle Dene', Culmstock Road, Hemyock, Devon: an Archaeological Excavation and Watching Brief Assessment Report" (PDF), Context One Archaeological Services, p. 6, retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Mackenzie 1896, p. 33; English Heritage, "Hemyock Castle Gatehouse and Curtain Walls, Hemyock", British Listed Buildings Online, retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Context One Archaeological Services (2009), "Land to the East of 'Castle Dene', Culmstock Road, Hemyock, Devon: an Archaeological Excavation and Watching Brief Assessment Report" (PDF), Context One Archaeological Services, p. 6, retrieved 24 August 2013.; English Heritage, "Hemyock Castle Gatehouse and Curtain Walls, Hemyock", British Listed Buildings Online, retrieved 24 August 2013.

- English Heritage, "Hemyock Castle Gatehouse and Curtain Walls, Hemyock", British Listed Buildings Online, retrieved 24 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Emery, Anthony (2006). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300-1500: Southern England. 3. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139449199.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896). The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure. 2. New York, US: Macmillan. OCLC 504892038.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Hemyock Castle - official site