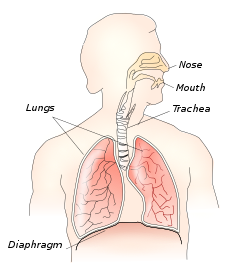

Thoracic diaphragm

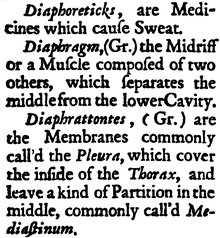

The thoracic diaphragm, or simply the diaphragm (Ancient Greek: διάφραγμα, romanized: diáphragma, lit. 'partition'), is a sheet of internal skeletal muscle[2] in humans and other mammals that extends across the bottom of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm separates the thoracic cavity, containing the heart and lungs, from the abdominal cavity and performs an important function in respiration: as the diaphragm contracts, the volume of the thoracic cavity increases, creating a negative pressure there, which draws air into the lungs.[3]

| Diaphragm | |

|---|---|

Respiratory system | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Septum transversum, pleuroperitoneal folds, body wall[1] |

| Artery | Pericardiacophrenic artery, musculophrenic artery, inferior phrenic arteries |

| Vein | Superior phrenic vein, inferior phrenic vein |

| Nerve | Phrenic and lower intercostal nerves |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Diaphragma |

| Greek | διάφραγμα |

| MeSH | D003964 |

| TA | A04.4.02.001 |

| FMA | 13295 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The term diaphragm in anatomy, created by Gerard of Cremona,[4] can refer to other flat structures such as the urogenital diaphragm or pelvic diaphragm, but "the diaphragm" generally refers to the thoracic diaphragm. In humans, the diaphragm is slightly asymmetric—its right half is higher up (superior) to the left half, since the large liver rests beneath the right half of the diaphragm. There is also a theory that the diaphragm is lower on the other side due to the presence of the heart.

Other mammals have diaphragms, and other vertebrates such as amphibians and reptiles have diaphragm-like structures, but important details of the anatomy may vary, such as the position of the lungs in the thoracic cavity.

Structure

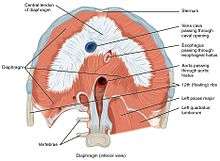

The diaphragm is a C-shaped structure of muscle and fibrous tissue that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdomen. The dome curves upwards. The superior surface of the dome forms the floor of the thoracic cavity, and the inferior surface the roof of the abdominal cavity.[5]

As a dome, the diaphragm has peripheral attachments to structures that make up the abdominal and chest walls. The muscle fibres from these attachments converge in a central tendon, which forms the crest of the dome.[5] Its peripheral part consists of muscular fibers that take origin from the circumference of the inferior thoracic aperture and converge to be inserted into a central tendon.

The muscle fibres of the diaphragm emerge from many surrounding structures. At the front, fibres insert into the xiphoid process and along the costal margin. Laterally, muscle fibers insert into ribs 6–12. In the back, muscle fibres insert into the vertebra at T12 and two appendages, the right and left crus, descend and insert into the lumbar vertebrae. Right crus arises from L1-L3 their intervertebral discs. Left crus from L1, L2 their intervertebral discs. [5][6]

There are two lumbocostal arches, a medial and a lateral, on either side.

Crura and central tendon

The left and right crura are tendons that blend with the anterior longitudinal ligament of the vertebral column.

The central tendon of the diaphragm is a thin but strong aponeurosis near the center of the vault formed by the muscle, closer to the front than to the back of the thorax, so that the posterior muscular fibers are the longer.

Openings

There are a number of openings in the diaphragm through which structures pass between the thorax and abdomen. There are three large openings—the aor[2]tic, the esophageal, and the caval opening—plus a series of smaller ones.

The inferior vena cava passes through the caval opening, a quadrilateral opening at the junction of the right and middle leaflets of the central tendon, so that its margins are tendinous. Surrounded by tendons, the opening is stretched open every time inspiration occurs. However, there has been argument that the caval opening actually constricts during inspiration. Since thoracic pressure decreases upon inspiration and draws the caval blood upwards toward the right atrium, increasing the size of the opening allows more blood to return to the heart, maximizing the efficacy of lowered thoracic pressure returning blood to the heart. The aorta does not pierce the diaphragm but rather passes behind it in between the left and right crus.

The thoracic spinal levels at which the three major structures pass through the diaphragm can be remembered by the number of letters contained in each structure:

- Vena Cava (8 letters) – Passes through the diaphragm at T8.

- Oesophagus (10 letters) – Passes through the diaphragm at T10.

- Aortic Hiatus (12 letters) – Descending aorta passes through the diaphragm at T12.

| ! Description | Vertebral level | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| caval opening | T8 | The caval opening passes through the central tendon of the diaphragm. It contains the inferior vena cava,[5] and some branches of the right phrenic nerve. |

| esophageal hiatus | T10 | The esophageal hiatus is situated in the posterior part of the diaphragm, located slightly left of the central tendon through the muscular sling of the right crus of the diaphragm. It contains the esophagus, and anterior and posterior vagal trunks.[5] |

| aortic hiatus | T12 | The aortic hiatus is in the posterior part of the diaphragm, between the left and right crus. It contains the aorta and the thoracic duct. |

| two lesser apertures of right crus | greater and lesser right splanchnic nerves and the azygos vein | |

| two lesser apertures of left crus | greater and lesser left splanchnic nerves and the hemiazygos vein | |

| behind the diaphragm, under the medial lumbocostal arch | sympathetic trunk | |

| areolar tissue between the sternal and costal parts (see also foramina of Morgagni) | the superior epigastric branch of the internal thoracic artery and some lymphatics from the abdominal wall and convex surface of the liver | |

| areolar tissue between the fibers springing from the medial and lateral lumbocostal arches | This interval is less constant; when this interval exists, the upper and back part of the kidney is separated from the pleura by areolar tissue only. |

Nerve supply

The diaphragm is primarily innervated by the phrenic nerve which is formed from the cervical nerves C3, C4 and C5.[5] While the central portion of the diaphragm sends sensory afferents via the phrenic nerve, the peripheral portions of the diaphragm send sensory afferents via the intercostal (T5–T11) and subcostal nerves (T12).

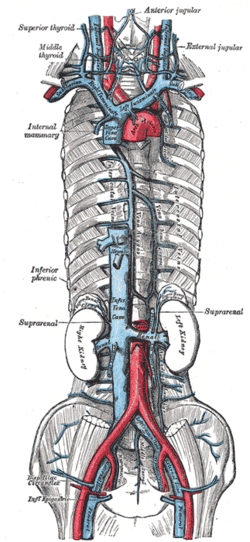

Blood supply

Arteries and veins above and below the diaphragm supply and drain blood.

From above, the diaphragm receives blood from branches of the internal thoracic arteries, namely the pericardiacophrenic artery and musculophrenic artery; from the superior phrenic arteries, which arise directly from the thoracic aorta; and from the lower internal intercostal arteries. From below, the inferior phrenic arteries supply the diaphragm.[5]

The diaphragm drains blood into the brachiocephalic veins, azygos veins, and veins that drain into the inferior vena cava and left suprarenal vein.[5]

Variation

The sternal portion of the muscle is sometimes wanting and more rarely defects occur in the lateral part of the central tendon or adjoining muscle fibers.

Development

The thoracic diaphragm develops during embryogenesis, beginning in the third week after fertilization with two processes known as transverse folding and longitudinal folding. The septum transversum, the primitive central tendon of the diaphragm, originates at the rostral pole of the embryo and is relocated during longitudinal folding to the ventral thoracic region. Transverse folding brings the body wall anteriorly to enclose the gut and body cavities. The pleuroperitoneal membrane and body wall myoblasts, from somatic lateral plate mesoderm, meet the septum transversum to close off the pericardio-peritoneal canals on either side of the presumptive esophagus, forming a barrier that separates the peritoneal and pleuropericardial cavities. Furthermore, dorsal mesenchyme surrounding the presumptive esophagus form the muscular crura of the diaphragm.

Because the earliest element of the embryological diaphragm, the septum transversum, forms in the cervical region, the phrenic nerve that innervates the diaphragm originates from the cervical spinal cord (C3,4, and 5). As the septum transversum descends inferiorly, the phrenic nerve follows, accounting for its circuitous route from the upper cervical vertebrae, around the pericardium, finally to innervate the diaphragm.

Function

The diaphragm is the main muscle of respiration and functions in breathing. During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts and moves in the inferior direction, enlarging the volume of the thoracic cavity and reducing intra-thoracic pressure (the external intercostal muscles also participate in this enlargement), forcing the lungs to expand. In other words, the diaphragm's movement downwards creates a partial vacuum in the thoracic cavity, which forces the lungs to expand to fill the void, drawing air in the process.

Cavity expansion happens in two extremes, along with intermediary forms. When the lower ribs are stabilized and the central tendon of the diaphragm is mobile, a contraction brings the insertion (central tendon) towards the origins and pushes the lower cavity towards the pelvis, allowing the thoracic cavity to expand downward. This is often called belly breathing. When the central tendon is stabilized and the lower ribs are mobile, a contraction lifts the origins (ribs) up towards the insertion (central tendon) which works in conjunction with other muscles to allow the ribs to slide and the thoracic cavity to expand laterally and upwards.

When the diaphragm relaxes, air is exhaled by elastic recoil process of the lung and the tissues lining the thoracic cavity. Assisting this function with muscular effort (called forced exhalation) involves the internal intercostal muscles used in conjunction with the abdominal muscles, which act as an antagonist paired with the diaphragm's contraction.

The diaphragm is also involved in non-respiratory functions. It helps to expel vomit, feces, and urine from the body by increasing intra-abdominal pressure, aids in childbirth,[7] and prevents acid reflux by exerting pressure on the esophagus as it passes through the esophageal hiatus.

In some non-human animals, the diaphragm is not crucial for breathing; a cow, for instance, can survive fairly asymptomatically with diaphragmatic paralysis as long as no massive aerobic metabolic demands are made of it.

Clinical significance

Paralysis

If either the phrenic nerve, cervical spine or brainstem is damaged, this will sever the nervous supply to the diaphragm. The most common damage to the phrenic nerve is by bronchial cancer, which usually only affects one side of the diaphragm. Other causes include Guillain–Barré syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus.[8]

Herniation

A hiatus hernia is a hernia common in adults in which parts of the lower esophagus or stomach that are normally in the abdomen pass/bulge abnormally through the diaphragm and are present in the thorax. Hernias are described as rolling, in which the hernia is beside the oesophagus, or sliding, in which the hernia directly involves the esophagus. These hernias are implicated in the development of reflux, as the different pressures between the thorax and abdomen normally act to keep pressure on the esophageal hiatus. With herniation, this pressure is no longer present, and the angle between the cardia of the stomach and the oesophagus disappear. Not all hiatus hernias cause symptoms however, although almost all people with Barrett's oesophagus or oesophagitis have a hiatus hernia.[8]

Hernias may also occur as a result of congenital malformation, a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. When the pleuroperitoneal membranes fail to fuse, the diaphragm does not act as an effective barrier between the abdomen and thorax. Herniation is usually of the left, and commonly through the posterior lumbocostal triangle, although rarely through the anterior foramen of Morgagni. The contents of the abdomen, including the intestines, may be present in the thorax, which may impact development of the growing lungs and lead to hypoplasia.[9] This condition is present in 0.8 - 5/10,000 births.[10] A large herniation has high mortality rate, and requires immediate surgical repair.[11]

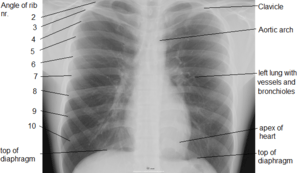

Imaging

Due to its position separating the thorax and abdomen, fluid abnormally present in the thorax, or air abnormally present in the abdomen, may collect on one side of the diaphragm. An X-ray may reveal this. Pleural effusion, in which there is fluid abnormally present between the two pleurae of the lungs, is detected by an X-ray of the chest, showing fluid collecting in the angle between the ribs and diaphragm.[8] An X-ray may also be used to reveal a pneumoperitoneum, in which there is gas in the abdomen.

An X-ray may also be used to check for herniation.[9]

Significance in strength training

The adoption of a deeper breathing pattern typically occurs during physical exercise in order to facilitate greater oxygen absorption. During this process the diaphragm more consistently adopts a lower position within the body's core. In addition to its primary role in breathing, the diaphragm also plays a secondary role in strengthening the posture of the core. This is especially evident during deep breathing where its generally lower position increases intra-abdominal pressure, which serves to strengthen the lumbar spine.[12]

The key to real core stabilization is to maintain the increased IAP while going through normal breathing cycles. […] The diaphragm then performs its breathing function at a lower position to facilitate a higher IAP.[12]

Therefore, if a person's diaphragm position is lower in general, through deep breathing, then this assists the strengthening of their core during that period. This can be an aid in strength training and other forms of athletic endeavour. For this reason, taking a deep breath or adopting a deeper breathing pattern is typically recommended when lifting heavy weights.

Other animals

The existence of a membrane separating the pharynx from the stomach can be traced widely among the chordates. Thus the model organism, the marine chordate lancelet, possesses an atriopore by which water exits the pharynx, which has been claimed (and disputed) to be homologous to structures in ascidians and hagfishes.[14] The tunicate epicardium separates digestive organs from the pharynx and heart, but the anus returns to the upper compartment to discharge wastes through an outgoing siphon.

Thus the diaphragm emerges in the context of a body plan that separated an upper feeding compartment from a lower digestive tract, but the point at which it originates is a matter of definition. Structures in fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds have been called diaphragms, but it has been argued that these structures are not homologous. For instance, the alligator diaphragmaticus muscle does not insert on the esophagus and does not affect pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter.[15] The lungs are located in the abdominal compartment of amphibians and reptiles, so that contraction of the diaphragm expels air from the lungs rather than drawing it into them. In birds and mammals, lungs are located above the diaphragm. The presence of an exceptionally well-preserved fossil of Sinosauropteryx, with lungs located beneath the diaphragm as in crocodiles, has been used to argue that dinosaurs could not have sustained an active warm-blooded physiology, or that birds could not have evolved from dinosaurs. An explanation for this (put forward in 1905), is that lungs originated beneath the diaphragm, but as the demands for respiration increased in warm-blooded birds and mammals, natural selection came to favor the parallel evolution of the herniation of the lungs from the abdominal cavity in both lineages.[13] However, birds do not have diaphragms. They do not breathe in the same way as mammals, and do not rely on creating a negative pressure in the thoracic cavity, at least not to the same extent. They rely on a rocking motion of the keel of the sternum to create local areas of reduced pressure to supply thin, membranous airsacs cranially and caudally to the fixed-volume, non-expansive lungs. A complicated system of valves and air sacs cycles air constantly over the absorption surfaces of the lungs so allowing maximal efficiency of gaseous exchange. Thus, birds do not have the reciprocal tidal breathing flow of mammals. On careful dissection, around eight air sacs can be clearly seen. They extend quite far caudally into the abdomen.[16]

See also

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 404 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- mslimb-012—Embryo Images at University of North Carolina

- Campbell, Neil A. (2009). Biology: Australian Version (8th ed.). Sydney: Pearson/Benjamin Cumings. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-4425-0221-5.

- "Medical Illustrations and Animations, Health and Science Stock Images and Videos, Royalty Free Licensing at Alila Medical Media". www.alilamedicalmedia.com.

- Arráez-Aybar, Luis-Alfonso; Bueno-López, José-L.; Raio, Nicolas (March 2015). "Toledo School of Translators and their influence on anatomical terminology". Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 198: 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2014.12.003 – via ResearchGate.

- Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- Moore, Keith (2014). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (7 ed.). Baltimore: Walters Kluwer. p. 306.

- Mazumdar, M.D. "Stage II Of Normal Labour". Gynaeonline. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- Nicki R. Colledge; Brian R. Walker; Stuart H. Ralston, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 644, 658–659, 864. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- Hay, William W., ed. (2011). Current diagnosis & treatment : pediatrics (20th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 602. ISBN 978-0-07-166444-8.

- Chandrasekharan, Praveen Kumar; Rawat, Munmun; Madappa, Rajeshwari; Rothstein, David H.; Lakshminrusimha, Satyan (2017-03-11). "Congenital Diaphragmatic hernia – a review". Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology. 3: 6. doi:10.1186/s40748-017-0045-1. ISSN 2054-958X. PMC 5356475. PMID 28331629.

- Nguyen, L; Guttman, F M; De Chadarévian, J P; Beardmore, H E; Karn, G M; Owen, H F; Murphy, D R (December 1983). "The mortality of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Is total pulmonary mass inadequate, no matter what?". Annals of Surgery. 198 (6): 766–770. doi:10.1097/00000658-198312000-00016. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1353227. PMID 6639179.

- "Diaphragm function for core stability » Hans Lindgren DC". hanslindgren.com.

- Arthur Keith, M.D. (1905). "The nature of the mammalian diaphragm and pleural cavities". Journal of Anatomy and Physiology.

- Zbynek Kozmik (1999). "Characterization of an amphioxus paired box gene, AmphiPax2/5/8" (PDF). Development. 126 (6): 1295–1304. PMID 10021347.

- T. J. Uriona (2005). "Structure and function of the esophagus of the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 208 (Pt 16): 3047–3053. doi:10.1242/jeb.01746. PMID 16081603.

- Dyce, Sack and Wensing in Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy; 2002 (3rd Edn); Saunders, Philiadelphia

![]()

External links